Introduction

The possibility of an armed conflict between Taiwan and China has received a disproportionate amount of attention in recent years. China’s actions, such as the increase of intrusions into Taiwan’s air-defense and identification zone (ADIZ) by fighter jets, poaching Taiwan’s diplomatic allies and squeezing Taiwan’s participation in international organizations, endangering Taiwanese society with misinformation/disinformation campaigns during elections and the pandemic, and engaging in military exercises, such as the one that shot missiles into six neighboring areas around Taiwan following U.S. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s 2022 visit, have all led observers to view Taiwan as possibly the most dangerous place on earth (The Economist 2021). If this report was not alarming enough, four-star U.S. general Mike Minihan has warned that an invasion could be on the horizon by 2025 (Campbell 2023).

The beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian war in February 2022 added more fuel to the topic, prompting the U.S. to assist the island with more overt military assistance and training programs. While some might argue that growing Chinese pressure might lead the Taiwanese citizenry to capitulate to Chinese coercion, Chong, Huang, and Wu (2023) found the contrary. Using data from the Taiwan National Security Studies (TNSS), their analysis revealed that compared to attitudes in 2016, citizens in 2020 were much more likely to support balancing than bandwagoning against China, the former defined as reducing economic engagement with China while increasing alliances with the U.S. and Japan against China.

Aside from economic choices, the urgency of the matter also leads many, including those living on the island, to ask: Are citizens in Taiwan willing to defend themselves if China invades? Specifically, what factors influence their willingness to engage in such self-defense? Our focus here is not to review all the existing polls on Taiwanese willingness to fight China, which have yielded a range from as low as 15% (e.g., results from the 2017 Taiwan National Security Study, TNSS) to as high as nearly 80% (e.g., results from a 2020 survey by the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy), and which could be influenced by questionnaire design, agency effects, and international events. Instead, our purpose in this review article is to take stock of what has been done in this burgeoning literature on Taiwanese support for self-defense, compare it with the Western war support literature, and consider what questions urgently need answers.

While one might label this burgeoning literature as “Taiwanese war support,” such phrasing would be misleading. The Western war support literature often probes public willingness to support a mission with goals such as economic gain or territorial expansion (Eichenberg and Stoll 2017). But these are not the main goals for Taiwan, for which, as Yeh and C. K. S. Wu (2021) note, the war would not be a choice but a necessity, for their survival. In a war with China, the mode of interaction for the Taiwanese would lean heavily toward defense, meaning that the country would not engage in a first strike, while there are ordinarily no such limitations for countries in the war support literature. Due to these reasons, we will use the term “public support for self-defense” in this article.

Taiwanese Willingness for Self-defense

U.S. Military Assistance, Gender, and Partisanship

One of the most persistent findings in the literature is that U.S. military assistance (in the form of troops) boosts the public’s willingness to defend themselves. In Wu et al.'s research (2022), the authors conducted a survey experiment and found that when citizens received information that “the U.S. will help defend Taiwan,” their willingness to fight China increased by about 7% on a 10-point scale. The effect remained positive even in a scenario where Taiwan was clearly the provocateur by declaring independence. The impression and belief of U.S. military assistance is deeply ingrained among the citizenry in Taiwan, to the extent that, in another survey experiment by W.-C. Wu et al. (2023), seeing Chinese fighter jets in a fictitious visual stimulus of Taiwan’s ADIZ led subjects to believe that the U.S. would deploy troops to help Taiwan more than seeing American fighter jets in the visual. The threat likely triggered the public’s belief that the U.S. would help if and when a conflict occurs.

Regarding individual factors, research on self-defense in Taiwan has consistently revealed the following findings.

First, analyzing 10 sets of TNSS data from 2002 to 2017 led Yeh and C. K. S. Wu (2021) to argue that female citizens are less likely to defend Taiwan in a conflict. In another correlational study, using seven representative surveys conducted by the Institute for National Defense and Security Research (INDSR), the think tank affiliated with Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense, and ranging from September 2021 to March 2023, Wang et al. (2023) reached the same conclusions. While these studies have not delved into why females demonstrate less willingness for self-defense, not having to serve in the military and unfamiliarity with weaponry could be contributing reasons.

Also, partisanship matters (e.g., Berinsky 2007). Partisans in Taiwan follow parties with varying ideologies, with supporters of the reigning Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) displaying a markedly higher level of willingness for self-defense than supporters of the pro-China Kuomintang (KMT). The polarization became even more evident following the Russo-Ukrainian war. Austin Wang from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, created a visualization with seven sets of INDSR data (see Figure 1). In each survey, respondents were asked the following: “If China invades Taiwan by force, are you willing to fight to defend Taiwan?”

Judging from the figure, clearly, the Russian invasion did not reduce willingness for self-defense among DPP supporters as the majority were still willing to defend Taiwan throughout the entire timespan. At the lowest point, around 88% of DPP supporters indicated they would fight. The same could not be said for the KMT, as willingness to defend Taiwan dropped to 38% eight months after the Russo-Ukrainian war began. Attitudes for supporters of the newly founded Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) mostly fall between those of DPP and KMT supporters. As the presidential candidate from the TPP continues to rise in the polls, willingness for self-defense in this group (primarily young voters under 40) would be essential.

Identity, Age, Generation, and Conscription

While war support in Western literature focuses less on identity, it is a salient issue in Taiwan as many in the country still regard themselves as both Taiwanese and Chinese. In an analysis using TNSS data, Taiwanese identity holders were more supportive of self-defense than Chinese identity holders (Yeh and Wu 2019). However, it would be erroneous to assume that the percentage in the population of solely Taiwanese identity holders will always increase. In fact, according to polling data collected by the Election Study Center at National Cheng-Chi University (https://esc.nccu.edu.tw/PageDoc/Detail?fid=7800&id=6961), between 2016 and 2018, the percentage of citizens who identified as “Taiwanese only” took a hit and dropped from 58.2 to 52.5. In explaining the sharp decline, Wang et al. (2023) proposed a theory—that citizens in Taiwan might take an instrumental view when it comes to their identity. In other words, after the DPP came into power in 2016, some of the Taiwanese identifiers turned out to be fair-weather friends. As the government began to receive criticism for poor performance and strained cross-Strait relations, this set of citizens could have decided to dissociate themselves from this particular identity.

In this vein, it is important to also pay attention to those with a dual identity, as many citizens might re-identify as both “Taiwanese and Chinese” when reverting from a Taiwanese-only identity. Wang and Eldemerdash (2023) found that compared to citizens who identified as Taiwanese only, those who did not have a solely Taiwanese identity were much more likely to rely on others’ behavior to decide their own actions if a war occurred. In the experiment they ran, simply telling this group that 82% of Taiwanese would resist a Chinese invasion rather than 18% increased their willingness to fight by nearly 22%.

Western literature on war support has not settled on a clear relationship between one’s age and war support, with some suggesting that older citizens are less supportive of wars (Mueller 1973; Page and Shapiro 1992), while others have found a positive relationship between age and willingness to fight in World War II (Cantril and Strunk 1951). The same could be said about the case of Taiwan. Age is found to correlate with willingness for self-defense negatively in C. K. S. Wu et al. (2022), but a positive relationship is recorded in other studies (e.g., W.-C. Wu 2023).

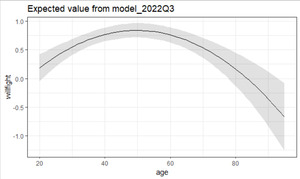

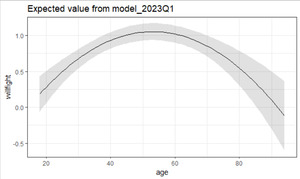

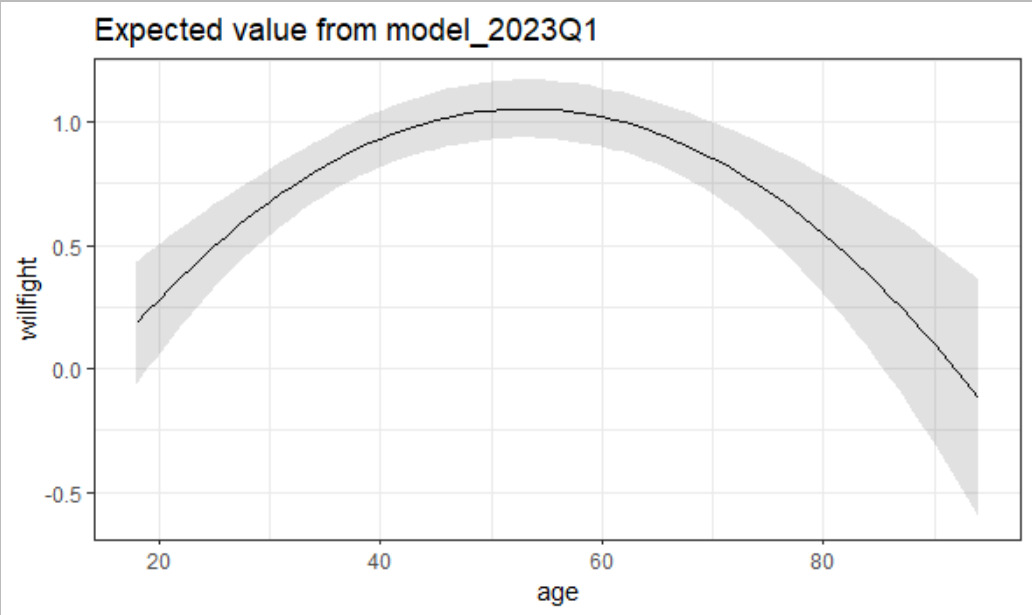

Wang et al.'s (2023) analysis using INDSR’s data from 2021 to 2023 might have presented an additional insight to help resolve the debate. They suggested a curvilinear relationship between age and willingness for self-defense. The three figures (Figures 2–4) below clearly demonstrate a curvilinear effect—willingness to fight peaks at around 50 years old and then goes down at both ends of the age range. The results are intuitive—if a war were to occur, the younger citizens would have to bear the brunt of the cost of the conflict, so they might be reluctant to fight. Many older citizens in Taiwan have memories of conflicts and were better trained militarily, which might be conducive to their higher level of willingness.

One way to corroborate the curvilinear hypothesis is to divide citizens into different generations. The Western war support literature has paid a fair amount of attention to the impact of generations on war attitudes, but the results are still inconclusive. The general consensus is that generations use their memories to make sense of future conflicts—citizens from the World War II generation see Hussein and Hitler as similar (Schuman and Rieger 1992); the Vietnam generation sees similarities between the Vietnam War and the Iraq War (Schuman and Corning 2006). Since generations do learn from their lived experience, one could argue that their learning should influence their support for future military operations. But empirically, the generation thesis does not have lot of support—Wilcox, Ferrara, and Alsop (1993) did not find evidence to support this conjecture. In fact, they find the contrary; the World War II generation that should have learned from the ill effects of appeasement were actually more pacifist than the Vietnam generation in thinking about future conflicts.

Different generations in Taiwan have experienced drastically different security environments and conscription policies. Many in their 70s and above might have fought in the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis, and most in their 50s experienced the Third Strait Crisis. Citizens in their 40s and above would have been requested to serve in the military for at least two years, whereas citizens in the younger generations serve a much shorter term, currently only four months. In the case of Taiwan, older generations have been found to demonstrate a higher willingness to fight. Yeh and C. K. S. Wu (2021) showed that citizens growing up through the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis, also known as the 823 Bombardment, were 3% more inclined to defend Taiwan in a conflict with China. Incorporating the results from TNSS 2019, C. K. S. Wu (2021) delineated four generations of Taiwanese citizens and came to a similar conclusion—citizens in the first and second generations (defined to include those born before 1959) were about 15% more willing to fight China than those in the fourth generation (born after 1987).

Contrary to the prevailing consensus in the Western literature that mandatory military service reduces war support (Vasquez 2005; Bergan 2009; Erikson and Stoker 2011; Horowitz and Levendusky 2011; Levy 2013; Kriner and Shen 2016), Taiwan presents a different case, as serving in the military is not a choice but an obligation for Taiwanese males. A study by Chen et al. (2022), using a representative survey, found that an individual’s perception of military training influenced their willingness for self-defense. Those who considered what they learned from the military to be useful on the battlefield were linked to a 5% increase on an 11-point scale item assessing respondents’ self-defense willingness, and the results were robust, with the exception of the Air Force, when different branches of the service (Army, Navy, Military Police, and Marines) were surveyed.

Unanswered Questions

Casualties

While the above studies have laid some foundational work to help us understand self-defense among citizens in Taiwan, many areas are still in dire need of research. First, we would like to call attention to studying the tolerance for casualties. Decades of research on war support from the Vietnam War to the War on Terror have all suggested that combat deaths is one of the most important determinants of war support (e.g., Mueller 1971), although the effect is conditional on other factors, such as one’s assessment of whether the country is going to prevail in the war and if the war fought is legitimate (Gelpi, Feaver, and Reifler 2005).

The literature has made limited headway on the number of casualties that Taiwanese citizens could accept. C. K. S. Wu et al. (2022) concluded that U.S. involvement did not significantly increase Taiwanese citizens’ acceptance of casualties. For instance, in a scenario in which Taiwan declared independence and the U.S. decided to assist Taiwan militarily, 35% of citizens would tolerate over 50,000 casualties; 32% would accept the same number even if the U.S. chose not to intervene. Another takeaway from this research was that Taiwanese tolerance for combat deaths is polarized. Although a sizable population (over 30%) could tolerate over 50,000 deaths across all four scenarios in the study, at least another 20% of citizens could not accept a single death. The findings are subject to a number of limitations. First, the survey was done in July 2019, so recent major changes in international and cross-Strait relations might have modified the tolerance. Second, since Taiwan has not experienced any armed conflict with China for at least six decades, citizens might genuinely have difficulties estimating or imaging battle deaths in the process of forming an opinion.

For future research, it might be helpful to contextualize the number of casualties by drawing from the war in Ukraine, considering the public’s familiarity with the case. To this date, there has not been an open source that clearly tracks military deaths of both sides in the war with consistency, so it might rather be helpful to make use of the statistics provided by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR 2023). According to their tracking, the cumulative Ukrainian civilian casualties from the inception of the invasion in February 2022 through July 2023 were 26,015 casualties (9,369 killed and 16,646 injured). Such information might give the Taiwanese public a benchmark for thinking about casualties.

War support research has demonstrated that citizens do respond to civilian casualties by decreasing their support for military action (Dill, Sagan, and Valentino 2023). However, research by Johns and Davies (2019) with U.S. and U.K. respondents showed that citizens are much more sensitive to military than civilian casualties. In other words, citizens reduce their war support when military deaths are notably higher.

It is unclear if such a tendency would appear in the context of a cross-Strait conflict. Many citizens in Taiwan perceive the military negatively, which might influence their sensitivity to military casualties as they might feel less sympathetic to military casualties compared to civilians in other countries, such as the U.S., where the military is clearly more respected. On the other hand, one could also conjecture that the public might take military deaths seriously, as the overall force numbers in Taiwan are limited (about 200,000), so significant military casualties would severely hamper the country’s ability to protect the citizens and defend the country.

Prospects for Success and Costs of War

A version of success for the citizens in a conflict with China might be that Taiwan could mount a successful defense against a Chinese invasion. While existing surveys have asked about citizens’ confidence in the military’s ability to protect them, individual assessments of what would constitute success or the prospect of a conflict are rarely made. A question from a poll by the Taiwan Public Opinion Foundation in June 2022 might be a helpful example. Citizens were asked if they believed Taiwan “could hold out for at least 100 days like Ukraine.” Out of 1079 surveyed, around 38% believed so, suggesting that a sizable portion of citizens are confident in Taiwan’s ability to prevail in a conflict (Taiwan Public Opinion Foundation 2022). There needs to be more research to tap into public belief about the likelihood of success in a conflict with China, because faith that they could prevail in a conflict could boost willingness for self-defense.

Another key factor that might influence citizens’ perception and calculation of the costs is the duration of a conflict. The longer the war, the greater the costs for a citizen in Taiwan. Sanaei (2019) found that in asymmetric wars (an armed conflict across the Strait would qualify), the longer time a country gets stuck in a conflict, the less support the government is going to receive for the war, controlling for the influence of casualties. Future work could apply Sanaei’s theory to see, in the context of a war of necessity, whether a similar finding would be reached.

A third factor to examine is the extent to which citizens in Taiwan would accept war as a necessary means to resolve the conflict across the Strait. Extending work by Eichenberg and Stoll (2017), there has been a growing anti-war movement in Taiwan, and the concept of acceptability of war could be used to gauge citizens’ willingness for self-defense, because willingness for self-defense and accepting the use of force to resolve cross-Strait disputes are two distinct topics. Citizens who believe that war is unnecessary should reduce their support for more defense spending, whereas those that believe war could be necessary would behave otherwise, although as research by Kriner, Lechase, and Zielinski (2018) has indicated, whether the money comes from the rich or the poor could have a drastic impact.

Willingness for Self-defense in the Military and Civil Defense Groups

Relatedly, this topic within the Taiwanese military is largely an untapped category in the literature. This issue has become increasingly more critical as reports showing that 20% of the force wants to leave before their contract is complete have started to appear (Trofimov and Wang 2023), and the country is now heavily reliant on a voluntary force. The morale of the soldiers, threat perception from China, belief in Taiwan’s ability to succeed, and the impact of joint training with U.S. forces are all key factors that should be entertained when gauging willingness for self-defense within Taiwan’s military.

Another point worthy of investigation is the extent to which civil defense groups in Taiwan impact public support for self-defense. Several civil defense organizations, such as the Kuma Academy (https://kuma-academy.org/) and the Forward Alliance (https://forward.org.tw/), came into prominence after the Russo-Ukrainian War began as citizens became aware of the need to prepare for a conflict across the Strait. Many hold a misperception about these civil defense groups that their main goals are to facilitate armed resistance among the citizenry—not so. Instead, these groups are working on increasing preparedness and resilience among the public in areas such as providing first aid, designing evacuation plans, and increasing media literacy to combat misinformation and cognitive warfare.

While more and more citizens participate in the workshops and seminars of these organizations, we have not come across a study that has dealt with the impact of such exposure on citizens’ willingness for self-defense. Results from the TNSS reveal initial success for these groups’ efforts, as citizens who said that they would “participate in local civil defense organizations” and “provide medical assistance” when a conflict occurred increased from 0.4% in 2020 to 2% in 2022 (C. K. S. Wu et al. 2023). It is worth examining whether such efforts manifest into changes in attitude toward self-defense.

Include Taiwan in the Western War Support Literature

From the vantage point of Western war support literature, Taiwan also presents an interesting case to push theoretical frontiers. Tomz and Weeks (2020) found that the public often retracts support for attacking a foreign country if the public is concerned about human rights, even when security implications are taken into consideration. But the flip side of the question has not been answered, that is, would the U.S. public be more willing to come to a weaker country’s defense against a more powerful adversary (i.e., Taiwan vs. China) if they believed that such an invasion might result in abuses of human rights or in other humanitarian consequences? Most would agree that the U.S. would likely come to Taiwan’s defense due to geopolitical concerns, but would concerns for human rights violations offer an additional boost?

We anticipate more studies on Taiwanese public support for self-defense to emerge as this topic is critical to both policymakers and international observers of cross-Strait relations and the triangular relationship between the United States, Taiwan, and China. The studies will help us better understand the complex range of public opinions in Taiwan and the factors that shape their self-defense willingness to demonstrate a higher level of deterrence. After all, support for self-defense would translate into public determination against an act of invasion/war when the act inevitably intrudes into their lives.

Corresponding Author

Charles Wu, wu@southalabama.edu

Department of Political Science and Criminal Justice, University of South Alabama