Introduction

Since the Sunflower Movement in 2014, political communication in Taiwan has increasingly embodied “digital populism,” shaped by social media dynamics. These practices combine personalized leadership with grassroots mobilization, leveraging online platforms to influence political agendas through affective diffusion and performative interaction. This article applies Mudde’s (2004) definition of populism as a thin-centered ideology positioning “the people (us)” against “the elites (them),” while also drawing on Moffitt’s (2016) framework of mediatized populism. Moffitt identifies three key elements: media logic, which governs agenda-setting in a platformized environment; affective mobilization, which drives collective action through emotions; and performative leadership, where politicians present themselves as true representatives of “the people.” This framework echoes Laclau’s (2005) concept of populist discourse as a radical form of democracy and aligns with Weyland’s (2001) view of populism as a strategy for mobilizing support.

Not all digital mobilization in Taiwan, however, signifies digital populism. Since the 2012 elections, social media, particularly Facebook, have become widespread in Taiwanese politics (Wang 2013; J.-C. Lin, d’Haenens, and Liao 2023). However, many efforts lack the antagonistic rhetoric, charismatic leadership, and thin-centered ideology central to populism. Tsai Ing-wen, for instance, uses Facebook and Instagram to project a relatable image but remains aligned with her party’s stable ideology (Chuang 2022). Local leaders like Wang Hao-yu and Molly Yen use social media to gain visibility, but their campaigns have remained short-lived and issue-specific (Feng 2020; Zhang 2023). These local movements, as Ho (2017) notes, mirror earlier, underfunded, and idealistic political figures and parties, which were often brief and localized in nature.

In contrast, Han Kuo-yu and Ko Wen-je have followed distinct political paths for nearly a decade. Han, while part of the mainstream Kuomintang (KMT), deviates from its traditional elite-driven approach by focusing on grassroots issues and direct voter engagement. Ko, a political outsider with a medical background, founded the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), positioning himself outside the dominant DPP (green) and KMT (blue) camps. Both have gained stable followings and sparked significant social phenomena. As Lin W. and Lin (2020) note, they reflect “the social origins of Taiwanese populism.” Han’s rhetoric has been analyzed through the lens of populist discourse, with studies by Batto (2021) and Krumbein (2023) highlighting its strategic use. Wu and Chu (2021) define Taiwan’s populism as a “bottom-up model,” rooted in post-Sunflower anti-establishment sentiment and a desire for direct democracy, with Ko’s rise also reflecting this demand for a bottom-up governance approach.

Both Han and Ko have built enduring digital populist presences, where affective engagement and charismatic leadership remain central to their appeal, extending beyond electoral cycles. This article treats them as critical exemplars of digital populism in Taiwan and aims to uncover the forms, mechanisms, and internal logic of this emerging mode of political communication.

Data Overview

This study examines Facebook activity by Han Kuo-yu and Ko Wen-je (2011–2025), tracking shifts in posting frequency, emotional tone, lexical focus, and topical themes to understand digital populism in Taiwan’s mediatized democracy. We collected posts from their official pages (Ko: 4,614 since 2011; Han: 1,861 since 2016) and analyzed them through temporal trends, Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) profiling, Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) analysis, and BERTopic topic modeling.

Consistent with prior work (Chuang 2022), interactions for both figures surged during elections, underscoring the link between online visibility and political timing. Ko peaked in 2018 (22 posts with >10,000 comments), while Han reached a high in 2019 (84 posts surpassing 10,000 comments; over 3.5 million total). Ko’s engagement remained steadier, whereas Han’s declined after 2020 before rebounding with his 2024 return to the Legislative Yuan; Ko saw a brief spike during 2025 controversies.

These patterns suggest digital mobilization in Taiwan is event-driven, tied to elections and scandals rather than sustained ideology. Han, backed by the KMT, leverages sporadic high-profile moments, while Ko compensates for a lack of party machinery with consistent exposure. This reflects thin-centered populism (Mudde 2004), where mobilization arises from situational opportunities, amplified by the platform logics of agenda-setting and attention competition (Moffitt 2016).

Trend 1: Emotional and Linguistic Dynamics in Rhetoric (LIWC Analysis)

We applied LIWC to assess the emotional tone of posts. Prior studies in psychology and political communication confirm its reliability and validity for capturing broad affective and cognitive patterns (Kahn et al. 2007).

The results show that both Han and Ko predominantly use positive emotion, challenging the assumption that populism is inherently tied to anger and fear (Wodak 2015). Han’s rhetoric is more affective, as reflected in his greater use of positive emotion (3.90 vs. Ko 2.47, social process terms (4.50 vs. 3.74), and motivational “Drives” (6.40 vs. 4.93), emphasizing warmth, gratitude, and collective identity. Ko, by contrast, leans toward rationality and policy, with higher cognitive process scores (7.03 vs. 6.64) and slightly greater use of informal expressions (2.52 vs. 2.28), projecting professional competence while remaining accessible. Overall, both avoid confrontational rhetoric and instead mobilize through positive, inclusive narratives that build trust and foster identification.

Trend 2: Thematic Patterns in Language Use (TF-IDF Analysis)

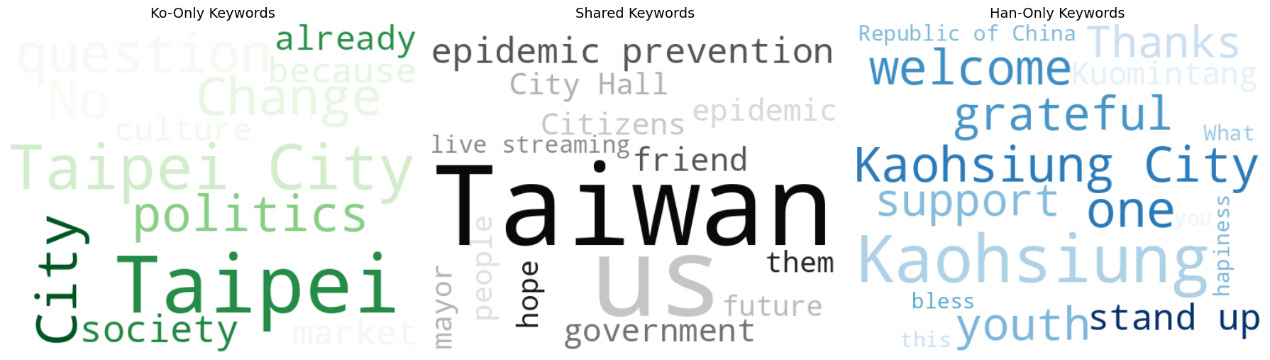

Building on the LIWC finding that both leaders rely on positive emotions rather than anger (Wodak 2015), TF-IDF further clarifies how they construct “the people” and the us-them divide.

The TF-IDF results highlight four thematic clusters: governance (e.g., “epidemic prevention,” “government,” “City Hall”), community/citizenship (“citizens,” “people,” “them”), identity/geography (“Taiwan,” “us”), and emotional/interactive terms (“hope,” “friend,” “future,” “live streaming”). Within these, “Taiwan” emerges as an empty signifier (Laclau 2005) through which both leaders claim to represent the collective will (Mudde 2004). Frequent references to “us” and “them” underscore their reliance on populist in-group/out-group distinctions.

Yet important differences remain. Ko Wen-je frequently invokes “Taipei,” “City Hall,” and political terms, projecting an image of urban governance and technocratic problem-solving. Han Kuo-yu, by contrast, stresses “Kaohsiung” and “Republic of China,” coupled with affective words such as “grateful,” “thanks,” and “stand up,” embedding his populism in emotional appeal, nationalism, and regional pride. This divergence aligns with the LIWC results: Han relies on emotionally charged rhetoric to mobilize collective action, while Ko emphasizes rationality and professionalism. Notably, Ko’s consistent use of “Taiwan” and “Taipei,” in both simplified and traditional Chinese, highlights his attempt to transcend the green-blue divide and project neutrality, whereas Han’s reliance on gratitude and blessing ties him more closely to ROC-based nationalism and local identity.

Trend 3: Thematic Clusters in Discourse (BERTopic Analysis)

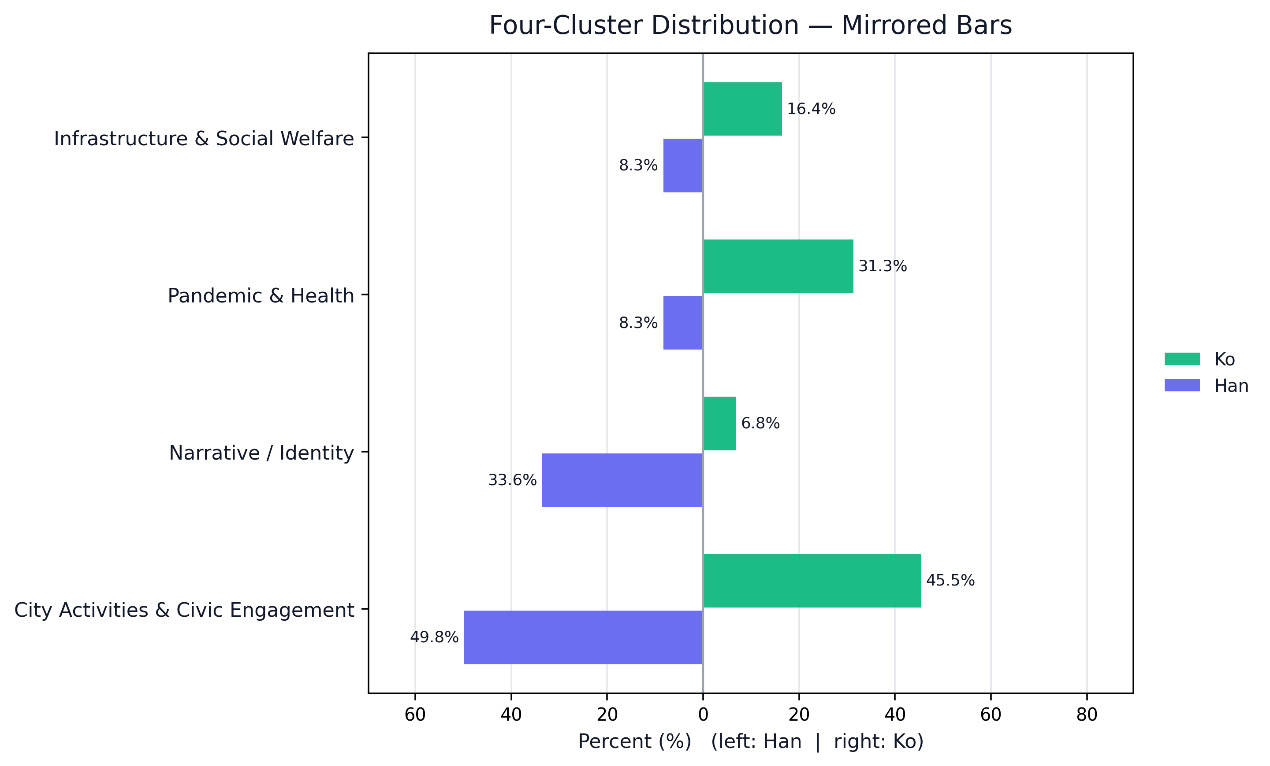

While TF-IDF identified four categories, namely governance, citizenship, identity, and emotion, our BERTopic analysis further refines these into four clusters: Narrative/Identity, Pandemic and Health, City Activities and Civic Engagement, and Infrastructure and Social Welfare. The emotional/interactive elements from TF-IDF were subsumed under Narrative/Identity to better capture how both politicians frame “the people.” Pandemic-related discussions formed a separate cluster due to the salience of COVID-19, a defining event during Han and Ko’s political careers.

In Narrative and Identity, Han dominates (33.6% vs. Ko’s 6.8%), emphasizing “Kaohsiung, Taiwan” and “Kuomintang, Taiwan” (word pairs identified by BERTopic analysis), which tie local pride to ROC nationalism. His rhetoric fuses Kaohsiung identity with the broader KMT/ROC framework, appealing through affect and nationalism. Ko, in contrast, foregrounds “Taipei” alongside international themes such as cross-Strait affairs and relations with the United States and Japan in order to articulate a civic narrative rooted in internationalism and technocratic neutrality. Rather than drawing on national or partisan identity, Ko’s discourse reflects what Sassen (2002) calls a “global city identity,” which represents a post-national civic orientation rooted in urban governance and transnational engagement. This city-based framing enables him to position Taipei as a cosmopolitan hub and himself as a non-partisan leader, offering an alternative to the traditional DPP-KMT dichotomy (Barber 2013).

In Pandemic and Health, Ko’s medical background drives his higher share (31.3% vs. Han’s 8.3%). Posts on “COVID-19, vaccine, testing” stress resource allocation and infrastructure, signaling technocratic competence. Han’s pandemic discourse (e.g., “prevention, mask, citizens”) emphasizes daily life in Kaohsiung and grassroots health measures, reflecting a localized, community-driven style.

In City Activities and Civic Engagement, both show strong involvement but diverge in tone. Nearly half of Han’s posts here (49.8%) focus on mobilization, youth participation, and cultural identity (e.g., “youth, Kaohsiung, future, bilingual”), often tied to nationalist sentiment with emotional narrative. Ko’s share (45.5%) emphasizes international cultural and sporting events (“cultural, festival, Taipei”), branding Taipei as a global city and showcasing policy-oriented civic engagement.

Finally, in Infrastructure and Social Welfare, Ko again leads (16.4% vs. Han’s 8.3%), discussing housing, transportation, and elder care (“public housing, transportation”), consistent with long-term urban planning and technocratic governance. Han’s focus, by contrast, is more episodic and crisis-driven (e.g., “flood, disaster, recovery,” “infrastructure, Kaohsiung”), using crises as opportunities for political engagement rather than addressing long-term planning.

The charts reveal marked differences in the topics of interest between Han Kuo-yu and Ko Wen-je over time, reflecting their evolving political positions and responses to changing contexts. For Han, there was a sharp increase in posts related to Narrative and Identity after about 2017, peaking around 2019 as he transitioned from Kaohsiung mayor to presidential candidate. His focus was primarily on local identity, party affiliation, and his connection to the Kuomintang (KMT). After 2020, as his ROC-centered approach became less popular among the public, he shifted to place more emphasis on direct political engagement. This shift led to a new peak in civic engagement, with intensified interactions focused on voter mobilization and election campaigns. While his focus on Pandemic and Health remained relatively low, it served as a tool for his crisis-driven political approach, using the pandemic as an opportunity for direct engagement and mobilization.

In contrast, Ko’s focus shifted towards Taipei’s international role and cross-Strait relations, especially after 2019. His pandemic-related posts, notably higher than Han’s, emphasized his leadership in public health and broader systemic issues, like health infrastructure and resource distribution. Ko’s technocratic expertise in public health reinforced his political legitimacy and his vision of Taipei as an international metropolis, setting him apart from Han’s more localized focus.

In City Activities and Civic Engagement, Han dominated local mobilization and cultural events, particularly during the 2020 elections, using emotional strategies to engage voters. Ko, while less intense, promoted international cultural events, emphasizing Taipei’s global image through initiatives like the Lantern Festival and sports events.

Regarding Infrastructure and Social Welfare, Ko’s focus was steady, prioritizing long-term urban planning, while Han’s engagement was more crisis-driven, reflecting his episodic response to events like flood recovery. This contrast highlights Han’s preference for immediate crisis management over systematic, long-term welfare concerns.

Overall, Ko’s gradual shift toward public health and urban modernization after 2020 reflects his policy-driven, technocratic approach, whereas Han’s strategies remained focused on emotional, event-driven mobilization. While both politicians reflect populist tendencies, Ko emphasizes policy continuity and internationalism, while Han channels local nationalism and emotional appeal to mobilize support.

Conclusion

This study examines how digital populism manifests in Taiwan through the social media activities of Han Kuo-yu and Ko Wen-je, revealing how each shapes their political image and mobilization strategies. Despite differences in style and focus, both politicians exemplify key aspects of digital populism, particularly through emotional resonance and interactive engagement. They frame the “us vs. them” dichotomy, positioning themselves as representatives of “the people,” a classic populist trait.

Han uses grassroots mobilization and emotion-driven strategies to reinforce local nationalism, evolving from an ROC-centered approach to more direct engagement after 2020. Ko, in contrast, advances a global city-oriented metropolitan identity marked by technocratic governance, civic neutrality, and international positioning, offering an alternative to both the DPP and KMT. His technocratic approach, evident in his pandemic discussions, relies on public health policies and an international urban image to break from the traditional blue-green divide.

These trends offer a foundation for future studies on Taiwan’s digital populism, showing how populism is driven by a “safe” communal identity (e.g., Han abandoned his ROC narrative and shifted to direct engagement after 2020). Most importantly, these forms of digital populism highlight the importance of sustained direct engagement. As Wu and Chu (2021) suggest, Taiwan’s populism reflects a strong desire for direct democracy.

Future research should expand the literature and qualitative analysis to explore the long-term impact of these digital mobilizations on Taiwan’s political landscape and the global evolution of digital populism, enriching our understanding of how social media-driven populist movements shape political communication in mediatized democracies.

Data and Code Availability Statement

All analysis in this paper was conducted using Python. Code scripts used to generate key figures (e.g., Figures 2, 4–8) are available as supplementary files submitted to the editorial system. These scripts can be used in any Python environment with the provided dataset.

The underlying dataset, which consists of raw Facebook post content by Han Kuo-yu and Ko Wen-je (2011–2025), is currently in the process of cleaning and annotation for use in the author’s doctoral dissertation. A publicly accessible version of the dataset, along with full documentation and metadata, will be uploaded to GitHub or a suitable open-access repository upon the completion of that work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares no conflict of interest.

The data covers each Facebook page until March 1, 2025. Ko Wen-je’s page began on October 20, 2011, with the last post in this dataset on February 27, 2025. Han Kuo-yu’s page began on November 23, 2016, with the last post in this dataset on February 25, 2025.

Category definitions (Pennebaker et al. 2015): Cognitive Processes—words about thinking and reasoning (e.g., because, think, should); Drives—goal-related motives (e.g., achieve, win, power); Emotional Processes—positive or negative feelings (e.g., happy, sad, angry); Social Processes—social interaction and relationships (e.g., friend, talk, they); Informal Language and Punctuation—casual expressions (e.g., slang, OK, um) and punctuation marks; Time and Grammar—time focus (past, present, future) and grammatical function words (e.g., pronouns, articles, auxiliary verbs).

Emotional subcategories (Pennebaker et al. 2015): Positive Emotion—words showing positive feelings (e.g., happy, love); Negative Emotion—negative feelings overall; Sadness—words of loss or sorrow; Anxiety—worry or nervousness; Anger—hostility or frustration.

Ko’s use of simplified and traditional Chinese (marked with asterisks in Figure 4) reflects in-group positioning. His higher TF-IDF scores result from his having posted about 2.5 times more than Han.

Details of the original BERTopic clustering output and the comparative re-grouping process are documented in the accompanying code files submitted with this manuscript.

.png)

.png)