I. Introduction

With the rise of various social media platforms, Taiwanese citizens now have more diverse options for accessing political information. On one hand, politicians have increasingly adopted different platforms to communicate with voters. On the other hand, voters tend to gravitate toward platforms that reflect their partisan echo chambers, using them to access political information that reinforces their preexisting beliefs. For instance, nearly all political parties in Taiwan use YouTube to promote their political messages, and supporters of the pan-Green camp and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) often access content aligned with their party preferences through keyword searches (L.-Y. Hsu and Lin 2023, 2024). As a result, it is crucial to examine how voters engage with different social media platforms (Wang et al. 2022), particularly how political activity online translates into real-world participation and shapes individuals’ attitudes toward democratic values (W.-C. Chang 2017; A. C. Chang 2019).

Among those emerging platforms, Douyin (抖音)—the Chinese version of the video-sharing application TikTok—has increasingly gained popularity. However, TikTok users are often perceived as being more sympathetic toward China and more likely to consume content aligned with Chinese political narratives. Existing research suggests that the Chinese government has leveraged TikTok to disseminate its worldview and even to promote the ideology aligned with China through light-hearted, entertaining short videos (X. Chen, Kaye, and Zeng 2021; Lu and Pan 2022; Guinaudeau, Munger, and Votta 2022; L. Zhao and Ye 2025). Specifically, it is often observed that the Chinese government recruits Internet commentators—commonly referred to as “50 cent party members (五毛黨)”—to disseminate pro-CCP narratives and suppress dissenting opinions on these platforms (King, Pan, and Roberts 2013). One notable incident involved an American teenager who had her TikTok account suspended after posting a video highlighting human rights violations against the Uighur Muslim minority in China (Maheshwari 2023).

More than one-fifth of Taiwanese adults reported having used TikTok or Douyin at least once within a three-month period in 2024 (Ministry of Digital Affairs 2024). Research has shown that Douyin disproportionately features content favorable to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and implicitly portrays Taiwan’s democratic system in a negative light—a pattern that appears significantly more pronounced than on platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, or Instagram (Finkelstein et al. 2025). As noted by Taiwanese think tank researcher Eric Hsu, such content may not directly alter the political identity of young people in Taiwan, but it may nonetheless reduce their perceived threat from China and weaken their willingness to resist it (C. Chen and Hetherington 2025). In light of the growing prevalence of Douyin in Taiwan, our preliminary study aims to explore patterns of Douyin usage and political identity among Taiwanese people in 2025. We analyze survey data[1] collected in the same year and merge the responses on Douyin usage and partisanship with data on political identity and sociodemographic characteristics provided by the Election Study Center (hereafter ESC) at National Chengchi University. Our results from descriptive analysis show that respondents who are pan-Blue supporters, self-identify as Chinese, and support unification with China constitute the largest group among Douyin users compared to pan-Green supporters. In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, our results also indicate that males and individuals above the age of 50 spend more time on Douyin than females and younger generations, respectively.

This study proceeds as follows. We first review the literature on how media consumption influences political perception and how Douyin may serve as a propaganda tool for the Chinese government. We then present the descriptive and exploratory analysis of our main variables and propose several explanations for noteworthy patterns. We conclude by discussing the influence of Douyin on political attitudes in Taiwan and suggesting directions for future research.

II. Literature Review

i. Influence of Social Media Platforms on Political Participation

With the rise of social media platforms, peoples are increasingly turning to them to consume political and campaign-related information, as compared to traditional media, such as television, radio, and newspapers (Wang 2021). These developments have prompted both scholars and policymakers to examine the political consequences of social media. For instance, Taiwanese people spend nearly two hours per day on YouTube (L.-Y. Hsu and Lin 2023). In Taiwan, such engagement has been shown to inspire offline political participation, including voting in elections, joining protests, and participating in social movements (A. C. Chang 2019). As a result, political parties have adopted the platforms to attract voters, who are in turn more likely to use keyword searches to explore content aligned with their party identification (L.-Y. Hsu and Lin 2023). Specifically, individuals who spend more time obtaining political information on social media may have their foreign policy preferences shaped by the content they consume (L.-Y. Hsu and Lin 2024). These findings suggest that voters with different party identifications may tend to exhibit distinct patterns in how they consume political information on social media.

As more people turn to social media for political information, social scientists and psychologists have become increasingly interested in understanding why and how voters engage with such content and whether they rely exclusively on certain platforms for political content. Lodge and Taber (2005) argue that affect plays a crucial role in political information processing: Individuals tend to seek information that aligns with their prior beliefs, as refuting incongruent statements demands greater cognitive effort. The psychological mechanism------whereby individuals prefer to engage with like-minded others------contributes to the formation of “echo chambers” on social media platforms. Specifically, partisan echo chambers strengthen the ties between individuals and their ideologically aligned co-partisans (Hobolt, Lawall, and Tilley 2024). As social media continue to evolve, individuals have more options across platforms. Consequently, they may be increasingly likely to remain with their partisan echo chambers and engage primarily with content that reinforces their prior or existing political views.

Conversely, exposure to cross-cutting perspectives that contradict an individual’s partisan orientations has been shown to suppress political engagement (Mutz 2002, 2006). Perceived cross-cutting exposure on platforms lacking politically congruent users may discourage individuals from expressing their views and reduce political participation (Lin 2022). Put simply, people are less likely to express political opinions on websites that lack partisan echo chambers congruent with their own views. However, interacting exclusively with like-minded individuals in such environments can hinder the verification of political information and thus pose a significant threat to the quality of democracy (Wang et al. 2022). Overall, the rise of new social media platforms has enabled individuals to selectively engage with platforms that align with their political viewpoints, thereby reshaping how political information is consumed and influencing the individuals’ positions on the partisan spectrum.

ii. TikTok as a Propaganda Tool: How Does It Change People’s Perception?

Previous research has examined why and how authoritarian governments employ social media platforms to censor content that is unfavorable to the regime. While the authoritarian government may not censor all criticism of the regime (King, Pan, and Roberts 2013), they often use social media to distract the public and reduce the threat of social unrest by promoting patriotic content—in the case of China, by cheerleading for the nation and glorifying the revolutionary history of the Communist Party (King, Pan, and Roberts 2017). It is worth noting that the Chinese government’s efforts at intervening in social media are not an uncommon phenomenon. For instance, regime-affiliated accounts on YouTube often disguise themselves as news broadcasters—so-called “puppet anchors”—to disseminate pro-China narratives (Carter et al. 2023). These accounts tend to focus on specific political issues and attack Taiwanese political figures, thereby shaping viewers’ political attitudes and perceptions. Other platforms, such as Little Red Book (Xiaohongshu, 小红书) (Zhe and Zhuang 2023) and TikTok (Network Contagion Research Institute (NCRI) 2023; Maheshwari 2023), have been linked to both the suppression of politically sensitive content and the strategic promotion of state-promoted narratives.

Douyin has become popular among users likely due to its abundance of entertainment content (Yang and Ha 2021) and a recommendation algorithm that effectively tailors content to users’ preferences (Z. Zhao et al. 2021). However, some of this seemingly casual and non-political content is characterized as “positive energy (zheng nengliang, 正能量),” serving as a vehicle for the state’s mainstream political ideology and promoting a playful form of online patriotism endorsed by the Chinese government (X. Chen, Kaye, and Zeng 2021). Empirical research indicates that a substantial portion of trending videos (42.5%) is produced by government-affiliated accounts (Lu and Pan 2022), which seek to maximize viewer attention through entertaining content designed to attract traffic and promote a form of “playful patriotism” (X. Chen, Kaye, and Zeng 2021). Douyin is an algorithmically driven platform (Guinaudeau, Munger, and Votta 2022), where even state-affiliated actors must compete with independent influencers for users’ attention. As a result, regime-linked accounts can reach a wide audience and disseminate ideological propaganda if they achieve high trending rankings by producing humorous videos paired with viral songs (Z. Zhao et al. 2021). In other words, government-sponsored accounts can only expand their exposure once they attain high trending status and are surfaced to users through algorithmic recommendations. This helps explain why not all regime-linked accounts promote overtly political content: They must first attract viewers through engaging material that is not explicitly propagandistic, only then leveraging that visibility to disseminate state political ideology (Lu and Pan 2021).

Due to the nature of algorithmic recommendation, viewership is less dependent on the accounts or content creators that users follow or like (Guinaudeau, Munger, and Votta 2022). This allows regime-affiliated accounts to reach a broader audience, including users who do not actively follow them, as long as their content generates sufficient engagement or visibility. Given this dynamic, it is reasonable to contend that those regime-affiliated accounts may affect people’s perception or attitudes toward China. In fact, studies have found that TikTok users in the United States are more likely to hold favorable views of China’s human rights record and are disproportionately exposed to pro-Chinese government narratives on the platform (Finkelstein et al. 2025). On the other hand, the phenomenon that Trump supporters are likely to use a specific website—for example, Truth Social (Y. Zhang et al. 2025)—suggests that people tend to stay with their partisan echo chamber and that such behavior may also reinforce their existing beliefs regarding politics.

Despite extensive research on the political impact of social media, less is known about how Taiwanese users engage with China-based platforms such as Douyin. In this context, consuming political information on different social media platforms affects Taiwanese people’s willingness to defend their country (Yeh, Lin, and Wu 2024) and shapes their perceptions of the Russo- Ukrainian War (Wang et al. 2024). Given that social media consumption may influence people’s attitudes, heavy users of Douyin in Taiwan could also display more positive attitudes toward China and a diminished perception of China as a threat to Taiwan’s security and sovereignty. Although a substantial body of prior research has examined how TikTok shapes individuals’ perception of China (Finkelstein et al. 2025) as well as how other social media platforms affect both online and offline participation (W.-C. Chang 2017; A. C. Chang 2019), it remains unclear how Taiwanese individuals with varying ideological orientations and sociodemographic backgrounds engage with a China-based social media platform. Therefore, this preliminary study seeks to address the gap by analyzing Douyin usage in Taiwan based on online survey data collected in 2025.

III. Who Uses Douyin? Evidence from Online Survey Data

In this section, we examine how Douyin usage patterns vary by partisanship, national identity, unification/independence preferences, and sociodemographic background among Taiwanese respondents. This study uses the online survey data from Chen (n.d.), which includes approximately 1,300 respondents, and merges it with political and sociodemographic variables from the ESC survey.[2] The “Survey on Core Political Attitudes” conducted by the ESC includes data from 1992 to 2025, allowing us to merge key variables—such as Douyin usage—with this dataset. In our survey, respondents were asked the following question: “Do you use short video social media platforms such as TikTok (or the Chinese version, Douyin)? On average, how much time do you spend on them per day?” Accordingly, the subsequent analysis of Douyin usage is based on this question. While it is challenging to assess the representativeness of the survey due to the nature of telephone interviews and the use of incentives, we address these concerns by clarifying the sampling constraints[3] and reporting detailed descriptive statistics in Appendix A, thereby ensuring transparency in how our results should be interpreted.

i. Partisan Identity, National Identity, and Unification/Independence Preference

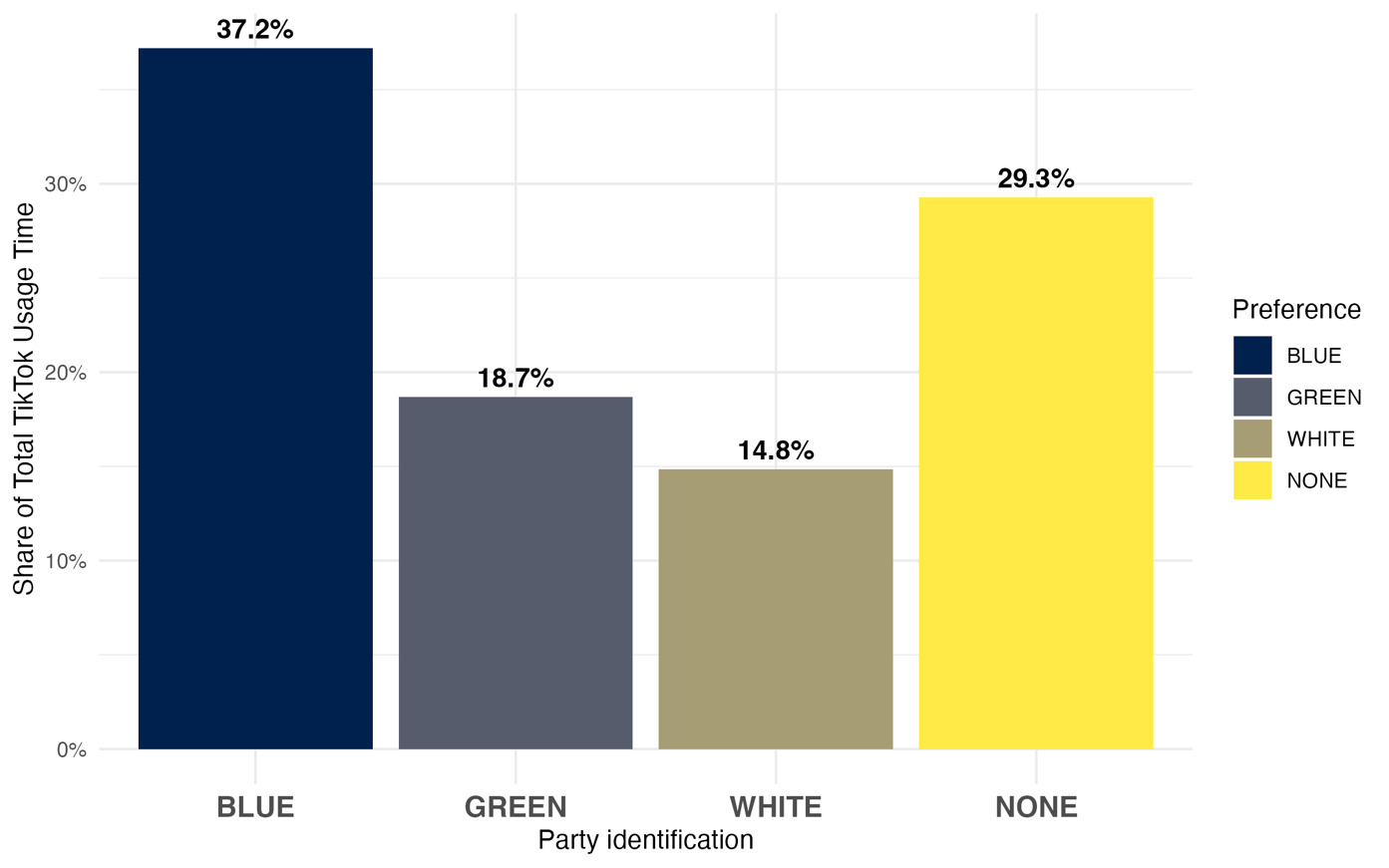

Prior research suggests that existing party or group identification shapes how people consume information on social media platforms (Redlawsk 2002; Lau and Redlawsk 2006). To examine whether similar patterns occur in Taiwan, this subsection presents the distribution of Douyin usage across party identification, national identity, and unification/independence preferences. Descriptive analysis reveals that KMT supporters are more likely to consume content on Douyin than DPP supporters. Furthermore, frequent Douyin users tend to support rapid unification with China and are more likely to identify as Chinese rather than Taiwanese. In this analysis, political identification is measured using the following survey question: “Among the major political parties in Taiwan, do you identify with any particular party?” Respondents’ answers are grouped into a four-point party preference scale: BLUE = Kuomintang (KMT) and affiliated pan-Blue parties; GREEN = Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and affiliated pan-Green parties; WHITE = Taiwan People’s Party (TPP); and NONE = No party affiliation. Using this four-point scale, we examine the relationship between political identity and Douyin usage. First, the distribution in Table C1 (see Appendix C) shows Douyin usage rates by partisan affiliation, with pan-Blue supporters (45.5%) significantly more likely to use the platform than pan-Green supporters (15.0%). In line with this pattern, Figure 1 indicates that pan-Blue supporters also report spending more time on Douyin than their pan-Green counterparts—accounting for 37.2% versus 18.7%, respectively, of total Douyin usage time. These findings underscore a substantial partisan divide in social media usage patterns.

In terms of national identity, we merge our survey data on Douyin usage with Chinese/Taiwanese identity data from the Electoral Study Center (ESC) at National Chengchi University. As shown in Figure 2, respondents who identify exclusively as Chinese use Douyin at the highest rate among various identity categories, with 53.0% reporting Douyin use. Notably, Figure 3 reveals that they spend significantly less time on Douyin (only 9.6% of total Douyin usage time) compared to those who identify as Taiwanese (43.7%). Although the results suggest that respondents who identify as Chinese are more likely to report using Douyin than those who identify as Taiwanese, this does not necessarily reflect their actual usage habits. In other words, Chinese-identified individuals may prefer to consume official media from the Chinese government or access similar content through other platforms. For instance, they may opt to use Facebook instead of Douyin, as they are more likely to have established echo chambers or networks on that platform. Consequently, they may not spend as much time on Douyin. In contrast, respondents who identify as Taiwanese tend to be younger and are more likely to use Douyin frequently for entertainment purposes. This highlighted a distinction between political identification and actual media consumption behavior, which warrants further empirical investigation.

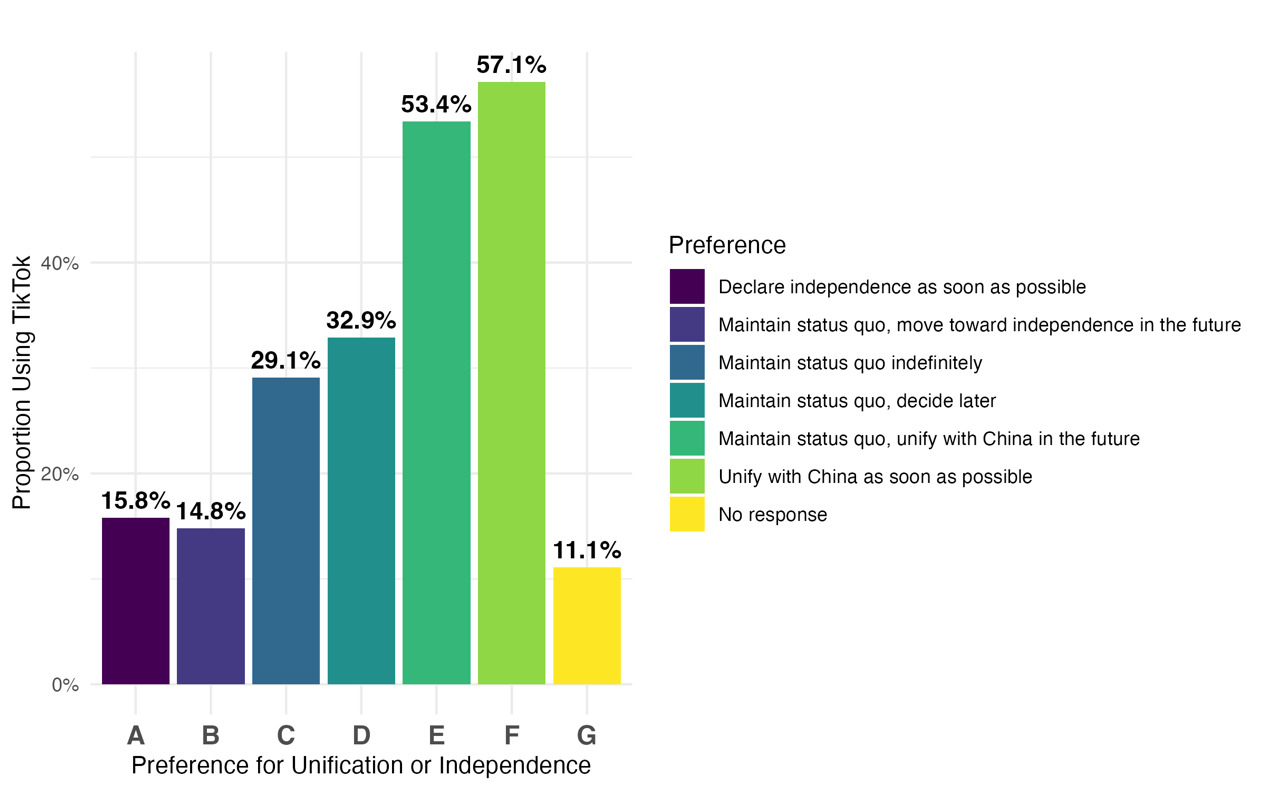

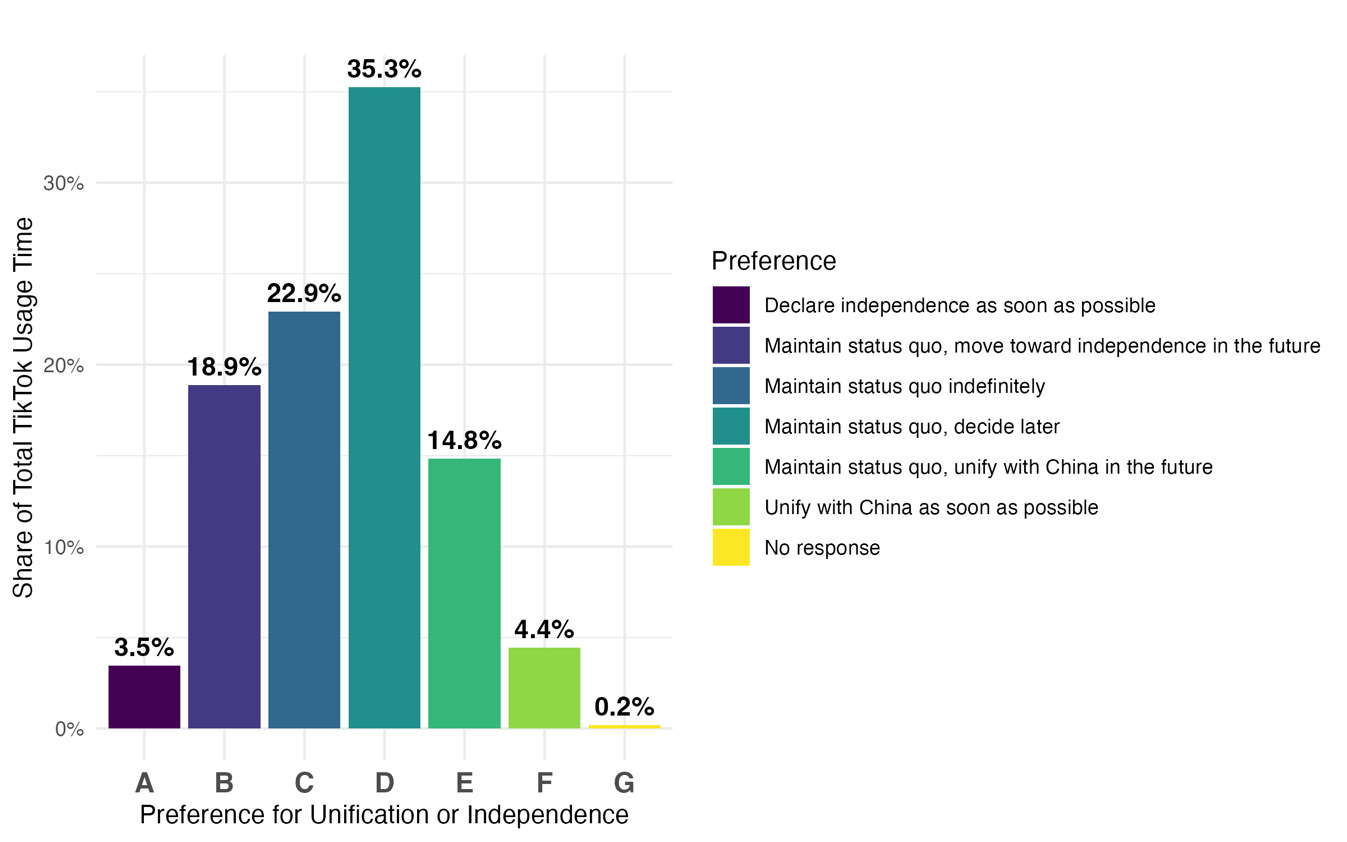

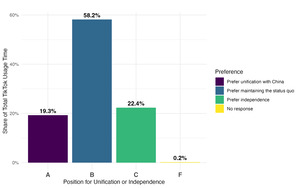

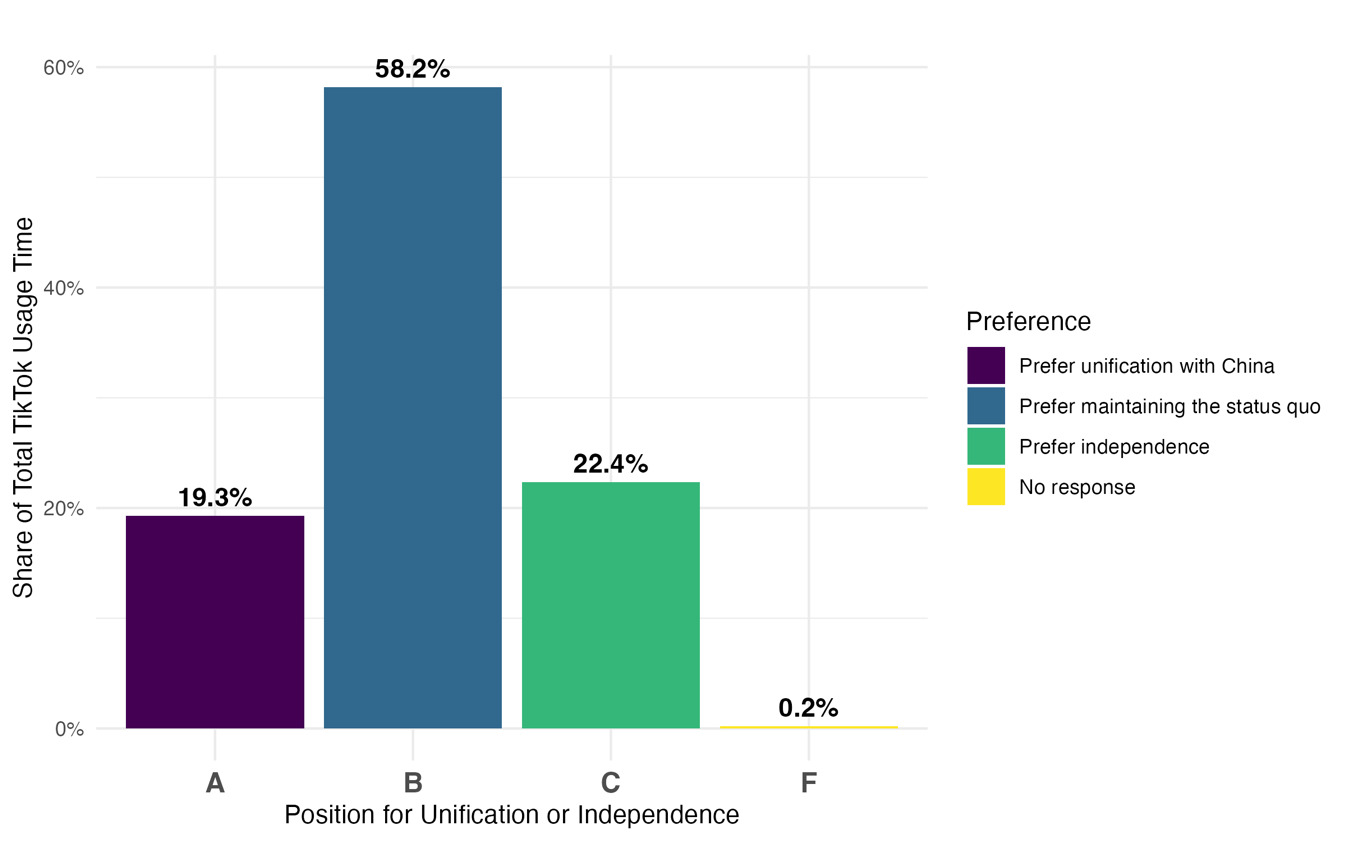

In analyzing unification/independence preferences, we visualize Douyin usage across respondents with varying stances. For clarity, we aggregate the original seven categories from the ESC (A = Declare independence as soon as possible; B = Maintain status quo, move toward independence in the future; C = Maintain status quo indefinitely; D = Maintain status quo, decide later; E = Maintain status quo, unify with China in the future; F = Unify with China as soon as possible; G = No response.) into four broader categories (A = Prefer unification with China, B = Prefer maintaining the status quo, C = Prefer independence, and F = No response). The main text presents results based on the four-category version, while the disaggregated seven-category analysis is provided in Appendix B. Observing the results with four categories shown in Figure 4, the Douyin usage rate is highest among respondents who support unification with China (54.1%), while those favoring independence exhibit a notably lower usage rate (15.0%). Interestingly, however, as seen in Figure 5, those who support maintaining the status quo tend to spend significantly more time on Douyin (58.2%) than those who support unification or independence (19.3% and 22.4%, respectively). Similarly, the results based on the seven-point scale shown in Figure B1 and Figure B2 consistently reveal the same trend. Given the popularity of social media among the younger generation (Y.-H. Chang and Guo 2022; T. Chen 2023), one possible explanation is that younger individuals without strong party affiliation may use Douyin more frequently due to peer influence and the opportunity to create self-media content to generate revenue. In this sense, their usage may be driven more by social or economic interests than by political motivations.[4]

ii. Demographics and Regional Distribution

In addition to preference for party and identity, it is worthwhile to explore the users’ habits on Douyin by sociodemographic background. For Douyin usage with respect to varying social-demographic backgrounds, we examine gender, age, geographic region (i.e., administrative area), and education level. First, the gender distribution among Douyin users also shows a difference, though not a substantial one. The breakdown of Douyin usage rates by gender (Appendix C, Table C3) indicates that a relatively larger proportion of males are Douyin users compared to females (29.1% of male respondents used Douyin versus 22.3% of female respondents). Also, males tend to use Douyin far more than females, with 63.2% of total usage time attributed to male users (Figure 6).

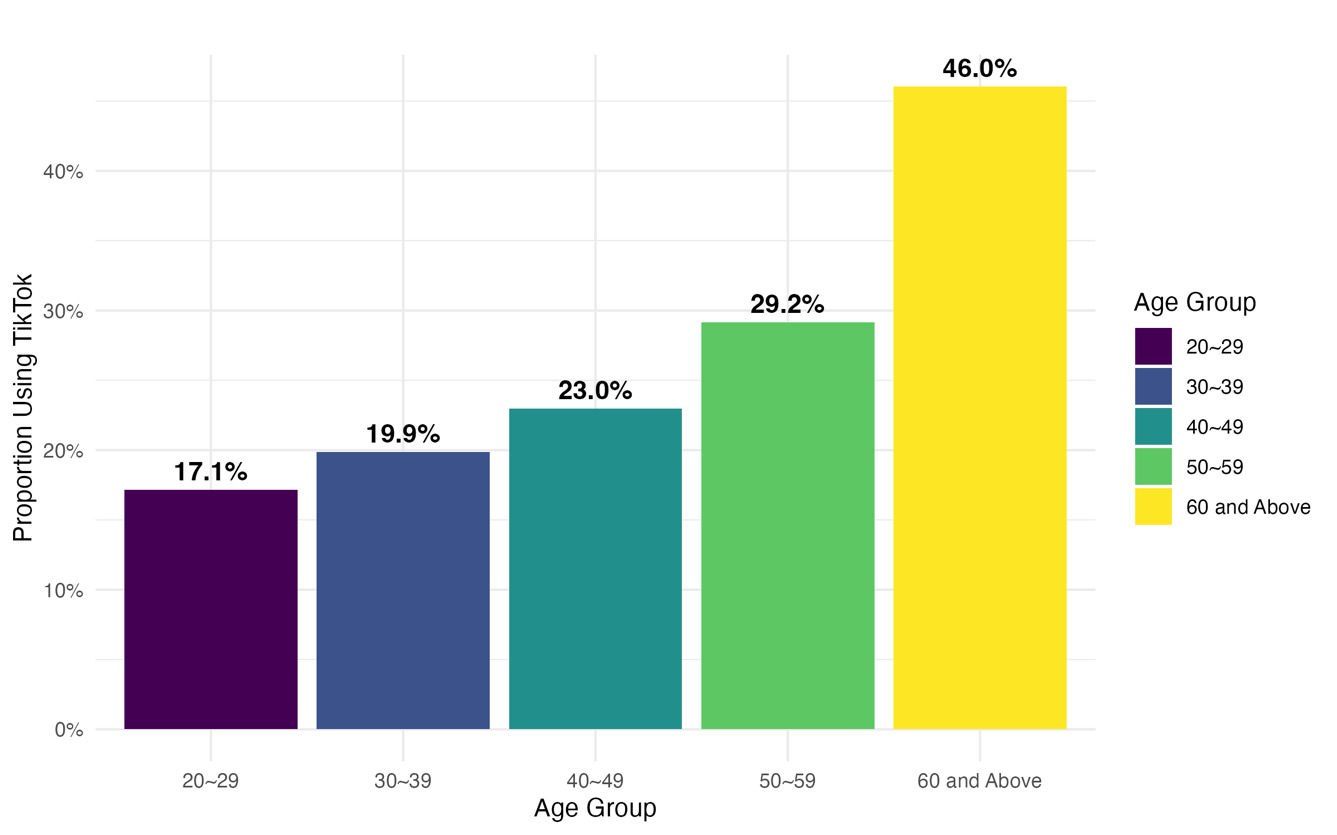

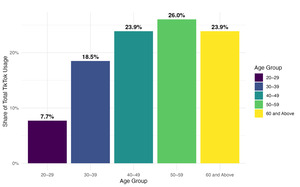

Next, regarding age, we find notable variation across generations in both the proportion that are users and the time spent on Douyin. The bar chart in Figure 7 shows that the Douyin users are distributed across different generations, with individuals 60 years old and above using Douyin at the highest rate. In terms of time spent on Douyin across age groups, the visualization in Figure 8 reveals that individuals aged 50–59 account for the largest share (26.0%) of total usage time, while those aged 40–49 and 60 and above each contribute 23.9%.

Contrary to the prevailing narrative that Douyin is predominantly used by the younger generation,[5] our findings reveal that respondents aged 60 and above constitute the largest share of users, while those aged 50–59 spend the most time on the platform. Prior research suggests that the flow experience—which connects interactivity and entertainment—plays a key role in fostering platform addiction among middle-aged users (Xu et al. 2025). Motivated by a search for social belonging and entertainment, many late middle-aged users turn to Douyin to stay connected with new technology, maintain social ties, and fulfill emotional needs in their everyday lives (Qiu 2022; Yu, Zhang, and Zhang 2024; Ma and Gao 2024). In the context of Taiwan, influencers often use Douyin to promote discounted daily goods------such as seafood, pork, or cookies------and share catchy, viral songs (e.g., “Kemu San, 科目三”, “Qiu Fo, 求佛”). This type of content in Douyin provides middle-aged users with opportunities to connect with younger generations while also fulfilling everyday practical needs.

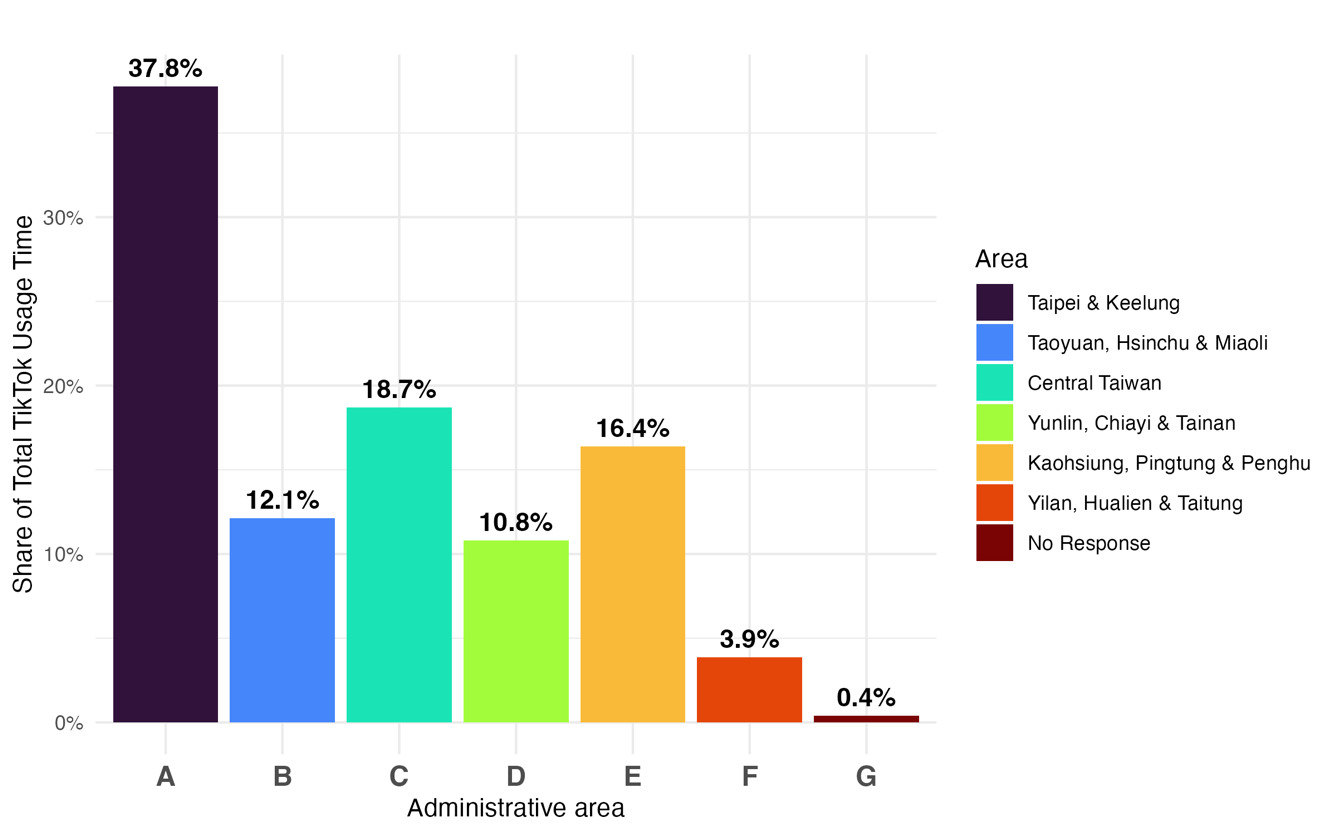

Beyond demographic distinctions in age and gender, Douyin usage also varies by geographic region and education, as shown in the following visualizations and in Appendix C. While Douyin usage rates show a relatively even distribution across administrative areas (Appendix C, Table C5), respondents living in the Taipei and Keelung area account for a larger share of time spent on the platform (37.8%) compared to those in other regions (Figure 9). Similar to the trend in China, Douyin users in Taiwan are primarily concentrated in urban areas, where higher population densities and better access to technological infrastructure facilitate greater platform engagement (Zhang, Mcfarlane et al. 2023). In addition, the rise of rural lifestyle influencers on Douyin may contribute to the platform’s popularity among urban users (X. Zhang 2020). Many urban residents have rural origins or share similar life experiences and values with these influencers, which fosters a sense of familiarity and emotional resonance with the content. Accordingly, future research should investigate the extent to which urban residents with rural origins are more likely to spend time on Douyin and whether some type of causal relationship can be established.

In terms of education, 34.4% of respondents who have attained middle or junior high school level use Douyin, the highest rate among the education groups (Appendix C, Table C6), whereas those who spend more time on the platform are predominantly individuals with a high school/vocational education or above (junior college) (Figure 10). The pattern in Table C6 may reflect the fact that individuals with lower levels of education are less likely to seek out complex or information-dense content------such as that found on Facebook or X (formerly Twitter)------and instead gravitate toward short-form, visually engaging platforms like Douyin. Future studies should examine whether individuals with lower levels of education are less inclined to consume knowledge-intensive content and how such consumption patterns might be related to their political attitudes or voting behavior.

IV. Conclusion

Social media platforms, along with their affiliated influencers, shape individuals’ perceptions of political information (W.-C. Chang 2017), influence both online and offline political engagement (A. C. Chang 2019; Lin 2022; Y.-H. Chang and Guo 2022), and can shift attitudes toward foreign policy (L.-Y. Hsu and Lin 2024). Moreover, in Taiwan, exposure to a wide range of social media sources may intensify political polarization (Wang et al. 2024). This effect becomes especially pronounced when voters are exposed to social media content outside their ideological echo chambers (Wang 2019; Yeh, Lin, and Wu 2024). Among newer social media platforms, Douyin (or TikTok) has been regarded as the one most frequently targeted by the Chinese government, more so than platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, or Instagram (Finkelstein et al. 2025). This is often achieved through tactics such as volume manipulation, in which pro-CCP content is algorithmically amplified to saturate users’ feeds and cultivate favorable public sentiment toward China (T. Hsu 2022, ; @493410; Finkelstein et al. 2025). Such interventions by the Chinese government have blurred the boundary between entertainment and propaganda (L. Zhao and Ye 2025), thereby increasing the likelihood of influencing the political attitudes of Taiwanese Douyin users. While Douyin usage may not directly shift core political attitudes—such as national identity or partisanship—it may, to some extent, erode individuals’ willingness to resist perceived threats from China (C. Chen and Hetherington 2025).

In this article, given Douyin’s growing influence in Taiwan, we shed light on usage patterns in relation to core political attitudes and sociodemographic characteristics. Combined with the online survey data from Chen (F.-Y. Chen, n.d.), our preliminary study reveals several noteworthy results. First, respondents who identify as pan-Blue, perceive themselves as Chinese, and express support for unification with China use Douyin at higher rates compared to their pan-Green counterparts. In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, our findings suggest that male respondents and those aged 50 and above tend to spend more time on Douyin than female and younger respondents, respectively. Interestingly, however, we found that Douyin users who support unification with China and identify as Chinese—while representing the largest proportion of users in terms of national identity and unification/independence preference—do not necessarily spend more time on that platform. Respondents who support maintaining the status quo tend to spend significantly more time on Douyin than those who support unification and independence (Figure 5). One of the possible explanations is that respondents who identify themselves as Chinese tend to be older, and therefore spend less time on smartphones compared to younger generations. On the other hand, from a commercial perspective, some content creators use China-based social media platforms to promote and sell their products. Teenagers without strong political preferences may spend substantial time engaging with such content for entertainment and trend-following purposes. Likewise, influencers may focus on sourcing products from China to resell, aiming to maximize attention and, in turn, economic profit, rather than aligning themselves with any particular stance on unification or independence preference.

Future research could build on these preliminary findings to explore the underlying mechanisms or theoretical explanations driving Douyin usage across different sociopolitical groups. Specifically, our analysis suggests that age may serve as a confounding variable in the relationship between identity or partisanship and Douyin usage. Future research should empirically assess whether this mechanism exists in the Taiwanese context. Next, given the growing number of internet users (Wang 2021) and the increasing prevalence of China-based social media platforms in Taiwan, it is crucial to examine how exposure to political content across different platforms may shape individuals’ political attitudes and contribute to political polarization (Wang et al. 2022). Building on our preliminary study of Douyin usage in Taiwan, future research should investigate several crucial questions, including whether political orientation influences social media platform choices and whether platform exposure influences political attitudes or voting behavior. More importantly, researchers should also investigate whether the use of different social media platforms has affected voter turnout and political efficacy in relation to radical political movements in recent years and how the Chinese government expands its influence through platforms beyond Douyin—such as those related to the pornography industry—by embedding pro-government narratives or positive imagery into pornographic content. In comparative context, it is also worthwhile to examine how China’s content manipulation strategies vary across countries worldwide and how individuals’ perceptions change in response. Chinese digital influence nowadays has become too significant to ignore. Future researchers should adopt a more circumspect approach when interpreting such phenomena and seek to unpack the black box of Chinese state intervention and behavior on social media platforms.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)