Introduction

While Taiwan’s populism has been characterized, a multidimensional framework clarifying its drivers remains absent from Taiwan-related literature. Addressing this gap will enhance the understanding of populism’s interaction and interplay with Taiwan’s social structure, enabling more comprehensive and accurate analysis of its practical manifestations. This paper identifies two drivers of Taiwan’s populism: economic anxiety and cultural backlash. Economic anxiety fuels Taiwanese populism through people’s economic insecurity and reliance on mainland China’s market. Cultural backlash propels it through Taiwanese natives’ resistance and the institutionalization of Taiwan’s nationalism, evolving into the repositioning of collective Taiwanese identity.

Populism in Taiwan

To clarify the contested concept of populism, I have adopted a communication perspective asserting that populism is a political style that aims at constructing antagonism between “the people” and “the elites/excluded others” (Jagers and Walgrave 2007). This communication perspective shifts the focus from the “who” of politics, as seen in the “thin ideology” approach (Mudde 2004) and the leader-centrism of the political-strategic approach (Weyland 2021), to a focus on how populism is disseminated (de Vreese et al. 2018).

Taiwan’s populism is characterized by constructing antagonism between Taiwanese people and the Kuomintang (KMT), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or mainland China. First, some NGOs and civil groups claim that the KMT’s authoritarian legacy remains a challenge to “the people” (C. Wu and Chu 2021), encompassing the KMT’s monopoly on traditional media, its substantial party assets, and the risk of corruption (Fell 2005). For example, during Ma Ying-jeou’s KMT government in 2012, some NGOs and civil groups launched the Anti-Media Monopoly Movement to oppose the Want Want China Times Media Group’s mergers with and acquisitions of traditional media, advocating for an anti-media monopoly law to safeguard people’s journalistic freedom (Ebsworth 2017).

Second, Taiwan’s post-KMT era has seen opposition parties employ anti-DPP rhetoric to describe the DPP government as authoritarian and against “the people.” For example, Huang Kuo-chang, the current leader of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a rally to “defend democracy, oppose authoritarianism” (護民主、反威權) on 22 February 2025, which maintained that the DPP would return Taiwan to the old path of one-party authoritarianism and trample on people’s democracy through a green authoritarianism (FTV News 民視新聞網 2025).

Third, some NGOs and civil groups raise concerns about mainland/Communist Party of China’s (CPC) infiltration of the people’s democracy and interference with the people’s sovereignty and freedom, along with the KMT’s complicity (C. Wu and Chu 2021). This distrust was evident during Ma Ying-jeou’s KMT administration (2008–2016), sparking student movements such as the 2008 Wild Strawberries Movement. This movement arose from discontent among pro-independence activists over the visit of Chen Yunlin, the chairman of the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS), and the controversy over police handling of protests (Fell 2017). They depicted Beijing’s influence, the police’s violence, and the KMT government’s reluctance at reforming the Assembly and Parade Act as threats to Taiwanese people’s sovereignty and human rights, thereby creating an “us versus them” dynamic against an external “Chinese other” and internal “KMT elites,” aligning with the definition of populism as constructing antagonism between “the people” and “the elites/excluded others” (Jagers and Walgrave 2007).

The above Taiwan-specific description of the antagonism between “the people” and the KMT/DPP/mainland embedded in Taiwan’s populist dissemination can be collectively analyzed from economic and cultural dimensions. I selected these two dimensions because they captured the demand side (the public’s reception) of populism by reflecting the public’s core discontent and anxieties (Inglehart and Norris 2016; Rodrik 2021) while simultaneously serving as targets that inform political actors’ populist strategies. In addition, they can be mutually linked in Taiwan when mobilizing “the people” against “elites” or “excluded others” as embodied by the KMT, DPP, and mainland China.

Taiwanese populism’s intertwined economic and cultural dimensions stem from mainland China-Taiwan relations and the DPP-KMT landscape. For example, economic anxieties, reflecting the discontent of economic “losers” under neoliberal capitalism (Rodrik 2021), can connect to a narrative questioning the loyalty or competence of the DPP or KMT. These parties are described as prioritizing partisan gain over people’s interests or, in the case of the KMT, as being overly accommodating to mainland China’s economic influence (Clark, Tan, and Ho 2020). In the latter case, these economic “losers” may feel not only financially marginalized but also that their unique Taiwanese way of life or democratic values are being undermined by policies drawing Taiwan closer to mainland China.

Thus, cultural backlash, reflecting voters’ discontent over declining traditional values (Inglehart and Norris 2016), has ties to the economic dimension in Taiwan. Taiwanese people’s demands for protecting Taiwan’s cultural subjectivity align with concerns about safeguarding Taiwan’s industries from mainland competition. Consequently, anti-China sentiment will extend Taiwanese cultural identity to anxieties about employment stability and a loss of economic autonomy.

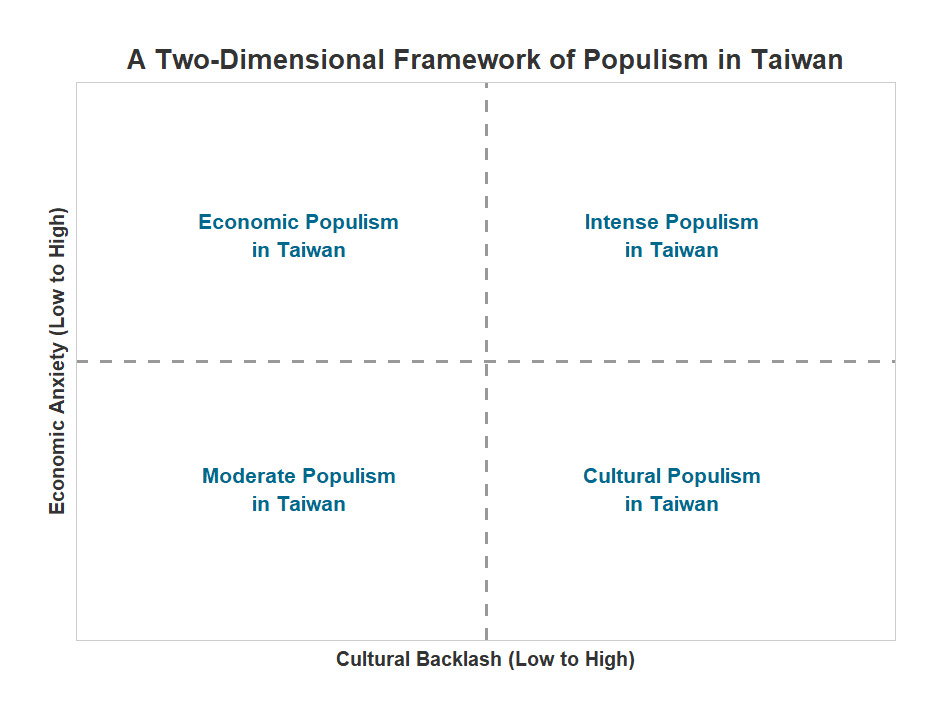

The above figure categorizes four types of populism in Taiwan based on the degree of economic anxiety and of cultural backlash in populist dissemination. Moderate populism lacks both economic and cultural dimensions. For example, Ko Wen-je appealed to “the people” in the 2014 Taipei election, emphasizing non-partisanship, transparency, and efficiency, rather than entrenched economic anxiety or cultural backlash (C. Wu and Chu 2021). Economic populism occurs when only economic anxiety is present. For example, Han Kuo-yu’s 2018 Kaohsiung election campaign highlighted the economic dimension, promising to improve livelihoods and blaming stagnation on the incumbent’s having deprived people of opportunities for prosperity (Batto 2021). Comparably, cultural populism emerges solely from cultural backlash. For example, Lee Teng-hui emphasized the cultural dimension, advocating for Taiwanese subjectivity and sovereignty to construct an antagonism between the Taiwanese people and mainland China (Ling 2011). Intense populism signifies the simultaneous presence of both economic and cultural dimensions. For example, the Sunflower Movement against cross-strait cooperation combined unemployment concerns (the economic dimension) and Taiwan’s sovereignty and democracy concerns (the cultural dimension), constructing an antagonism between Taiwanese people and KMT elites/Beijing (Clark, Tan, and Ho 2020).

Economic anxiety

Taiwan’s economic anxiety manifests in two aspects: (a) economic insecurity and (b) dependence on mainland China.

Economic insecurity refers to an individual’s subjective perception of economic uncertainty or vulnerability, including insecurity about unemployment, the effects of globalization and automation, and the effects of financial crises (Guiso et al. 2024). In Taiwan, this insecurity fuels public discontent and feelings of helplessness with regard to Taiwan’s stagnant economy; poor working conditions, class solidarity, and a perception of unfair resource (re)distribution are also involved (Tsai and Pan 2021). These dissatisfactions, in turn, integrate economic insecurity into Taiwanese populist tendencies. Tsai and Pan (2021) found that populist tendencies have significant relationships with citizens’ economic level, including poor household finances, deficits in household income versus expenditure, and a standard of living not matched by effort. Thus, economic insecurity serves as a demand-side driver for populist appeals, as Taiwanese seek solutions to improve their livelihoods and defend them against perceived threats from unfair economic structures and the privileged elite.

A structural factor contributing to economic insecurity, especially in southern Taiwan, is the north-south imbalance. This stems from past governments’ policies that have overly concentrated high-value-added industries, financial services, and infrastructure in the north. For instance, the Chen Shui-bian government’s efforts to promote financial liberalization and major infrastructure projects led to a massive concentration of financial assets and business opportunities in northern metropolitan areas, while leading to marginalized development and declines in financial services in many southern and rural areas (Hsu 2009). As northern industries integrate into global supply chains, the south’s traditional agriculture and manufacturing increasingly depend on direct exports, particularly into mainland China’s market. This clash fueled populist sentiment in southern Taiwan, actively leveraged by Han Kuo-yu. He used the slogan “no walls, only roads” (沒有墻,只有路) to promote Kaohsiung agricultural exports to the mainland, ridiculing Taipei elites for sacrificing Kaohsiung’s economy by severing cross-strait ties (Krumbein 2023).

In the economic realm, Taiwan’s unique relationship with mainland China has had dual impacts on its populism. The China factor not only represents economic opportunities under KMT-led clientelism, conversely it also embodies potential threats of economic influence as perceived by the DPP. While both the KMT and DPP utilized populism, their “elite” constructions and proposed solutions differ: KMT-led economic populism capitalizes on mainland China’s economic opportunities and blames the DPP for thwarting those, whereas DPP-led populism emphasizes the people’s economic sovereignty, portraying the China factor and the KMT’s cross-strait advocacy as threats to that sovereignty.

On the one hand, closer economic ties with mainland China provide political opportunities for the KMT to engage in clientelism involving Taiwanese businesses and Beijing (C. Wu and Chu 2021). Through the relaxation of trade policies and through market access and investment initiatives, the economic benefits of cross-strait cooperation can be transmitted through networks that the KMT has established with local factions. In other words, the KMT has traded political power for electoral support from local factions (Sullivan and Lee 2021). Hence, this populism appeals to those who see themselves as benefiting from cross-strait exchanges, such as farmers, tourism workers, and merchants in the south, and allows the KMT to portray the Taipei government as “an elite” that hinders the southerners’ prosperity for political reasons (Batto 2021). In this context, the KMT’s response to voters’ economic anxiety (demand-side) in the south and its promises to provide economic patronage from the mainland manifest one type of economic populism.

On the other hand, this reliance on mainland China has brought about public insecurity, which has fueled public discontent with threats to Taiwan’s economic autonomy and sovereignty, ultimately providing fertile ground for populist sentiments of another sort in the cross-strait confrontation. This was evident in the 2014 Sunflower Movement, in which Taiwanese youth protested the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA) due to fears of growing Chinese political influence through economic cooperation (Clark, Tan, and Ho 2020). This movement was characterized by public concern that the entry of Chinese capital would impact local jobs and markets, along with anger over the lack of transparency and disregard for democratic processes in the CSSTA negotiations (Y.-A. Wu and Hsieh 2014). These concerns represented a populist rejection of the KMT’s elite-led agenda, intensifying skepticism about whether the KMT would defend Taiwan’s economic rights against mainland China. Conversely, this movement enhanced people’s trust in the DPP as they advocated for more transparency, stronger democratic oversight, and a more careful approach to cross-strait exchanges (Y.-A. Wu and Hsieh 2014). The Sunflower Movement highlighted how public insecurity regarding mainland China’s influence, compounded by absent democratic procedures and the ruling party’s disregard for popular appeals, fueled anti-China and anti-elitist populism.

Cultural backlash

Taiwan does not share Western democracies’ cultural backlash concerning traditional values being challenged, as embodied by voters’ cultural angst concerning the decline of Christianity or cultural changes deriving from Muslim immigration. Rather, cultural backlash manifests as a unique phenomenon in Taiwan in which the public is discontented with the rising Taiwanese identity being curbed by traditional, conservative, and external forces. In other words, this cultural backlash represents a reaction against the threat to the “emerging” Taiwanese collective identity. This discontent serves as a demand-side driver for populism, constructing an antagonism between Taiwanese people’s cultural/identity subjectivity and pressures from conservative elites or external influences. Taiwan’s cultural backlash acts as a catalyst that strengthens collective re-evaluation and consolidation, mobilizing Taiwanese resistance to “traditional” identities inherited from previous colonial and authoritarian periods and echoed in today’s mainland influence. Hence, cultural backlash in Taiwan has contributed significantly to Taiwan’s nationalism, which in turn drives the repositioning of Taiwanese collective identity. This cultural backlash process has undergone two stages, encompassing (a) the native Taiwanese resistance and (b) the consolidation of civic nationalism.

The historical dimension of Taiwanese native resistance is crucial to understanding Taiwan’s cultural backlash; it laid the groundwork for populist appeals by putting “the people” (native Taiwanese) and external “elites” (colonizers and authoritarian forces) in opposition. This resistance, stemming from the oppression and marginalization of Taiwanese identity by different regimes, such as that of the Dutch (and Spanish), Ming (Cheng Ch’eng-kung regime), Qing Dynasty, Japanese, and KMT (under Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo) (Fell 2005), has led to the formation of a narrative of people’s discontent with external and authoritarian forces, which is at the core of populist mobilization.

Japan’s colonial rule (1895–1945) fostered early Taiwanese nationalism. The Kominka (Japanization) movement (1937–1945) under Seizo Kobayashi, through enforced linguistic, naming, military, and religious assimilation (Chou 2016), profoundly shaped identity conflict. This triggered native Taiwanese consciousness against colonial elites, founding a collective resistance identity. Despite limited cultural resistance movements in the 1930s, such as the Nativist Literature Polemic (鄉土文學論戰) and the Taiwanese Vernacular Polemic (台灣話文論戰) advocating for local language and literature (Chang 2018), cultural suppression bred people’s discontent, a premise for subsequent culturally-rooted populism.

The KMT’s authoritarian rule (1949–1987) further reinforced populist confrontation between the native population and external elites, rooted in the resistance of natives to the Chinese identity imposed on them. Taiwanese identity was marginalized again, while Chinese identity was imposed across three dimensions: language, social movement, and politics.

Regarding language, the KMT government initiated the Chinese Language Campaign in 1945 to eradicate Japanese influence (Hsiau 1997). Policies like the rapid discontinuation of Japanese media (1946), the exclusive use of Mandarin in schools (1951), and daily limits on native dialect television broadcasts (1972) systematically suppressed local languages (Chen 2010). These de-Taiwanized language policies disrupted the daily lives of natives and triggered their resentment against a KMT regime that suppressed their accustomed language. This collective resentment became a source of anti-elite/Chinese sentiment, consistent with the populist narrative that the people’s local culture was being trampled on by external elites again.

Regarding social movements, the KMT government launched the Chinese Cultural Renaissance in 1967 to preserve traditional Chinese culture. Despite its stated aim to counter mainland China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), the movement also reinforced Chinese cultural influence in Taiwan, further solidifying Chinese identity and hindering the development of Taiwan’s local culture (Tozer 1970). This also alienated natives from external elites, laying the groundwork for a cultural backlash in which natives could claim the re-establishment of Taiwanization as a counter to the imposed trend toward greater Sinicization.

Regarding the political dimension, the KMT’s discriminatory policy of predominantly appointing mainland immigrants to military, governmental, and educational positions (軍公教) while excluding Taiwanese natives from these roles (Fell 2005) caused disillusionment. This undermined the initial belief among Taiwanese that reunification with mainland China would empower them and led to increased questioning of and a repositioning of their cultural identity as potentially Japanese, Chinese, or distinctly Taiwanese (Shih 2021). This antagonism between us (discriminated-against natives) and them (mainland immigrants) is the cornerstone of populist rhetoric. The 1947 February 28th Incident was a catalyst that triggered people’s resistance to mainland immigrants and Chinese identity (Edmondson 2015). This trauma consolidated the collective Taiwanese identity formed in the course of confronting the KMT elite and continued to build up anti-establishment sentiment, which provided the basis for future populist movements. Thus, continued oppression under KMT rule, similar to that of early colonial experiences, forged a deep-rooted native consciousness and Taiwanese identity rooted in resistance. Ultimately, the lifting of Martial Law in 1987, constitutional reforms, and the first direct presidential election in 1996 triggered an explosive resurgence of Taiwanese identity, an unleashing of natives’ long-suppressed, intense aspirations for self-identity, which provided fertile ground for populists to utilize Taiwanese identity against alleged “elites” and authoritarian legacies.

Besides historical resistance, the consolidation of a civic nationalism that integrates the collective identities of native Taiwanese and mainland immigrants provides the basis for populist politics in Taiwan. Based on the repositioning of Taiwanese identity, populists can mobilize citizens to counter threats to this civic nationalism, whether those threats come from internal “elites” obsessed with Chinese identity or from external pressures from mainland China. Peng Ming-min, Lee Teng-hui, Chen Shui-bian, and Tsai Ing-wen promoted this civic nationalism, contributing to its populist potential by mobilizing the demand-side of cultural backlash.

First, Peng Ming-min, known as the “godfather of Taiwan independence,” drafted The Declaration of Formosan Self-salvation (台灣自救運動宣言) in 1964. This declaration sought to overthrow Chiang Kai-shek’s authoritarian KMT regime, establish democratic politics, and build a new nation uniting mainland immigrants and Taiwanese natives. This constructed an “us versus them” (them being the KMT) narrative, foundational for populism (Cheng 2024). Consequently, this declaration stimulated the Tangwai movement during the late Martial Law period and fueled a cultural backlash rooted in the idea of Taiwan’s independence that persists to this day (Cheng 2024).

Second, civic nationalism in Taiwan began to be institutionalized as a populist platform during Lee Teng-hui’s KMT government (1996–2000). Lee Teng-hui coined the phrase “new Taiwanese” (新台灣人) in 1998. The “new Taiwanese” sought to redefine “the people” by their shared democratic values and recognition of Taiwanese identity (Fell 2005). Ma Ying-jeou’s successful utilization of the “new Taiwanese” concept in the 1998 Taipei mayoral campaign proved its effectiveness as a populist tool (Kaeding 2009). On this basis, Lee Teng-hui further proposed the “Special State-to-State Relationship” (Two-State Theory) in 1999. This theory aimed to counter Beijing’s “one country, two systems” (Ling 2011), normalize Taiwan’s statehood, and emphasize Taiwanese subjectivity. This move mobilized popular concern for Taiwan’s dignity and autonomy, laying the groundwork for future populist antagonism toward mainland China on the identity and cultural levels (Clark, Tan, and Ho 2020).

Third, during the Chen Shui-bian DPP government (2000–2008), Taiwan-centric cultural identity and civic nationalism were further solidified and translated into specific populist policies. Building on Lee Teng-hui’s civic nationalism, Chen Shui-bian proposed “One Country on Each Side” in 2002. This concept was operationalized through policies that differentiated Chinese culture from Taiwanese identity (Corcuff 2011). For instance, Taiwan’s Ministry of Education adopted Tongyong Pinyin (通用拼音) to replace the mainland-derived Hanyu Pinyin (漢語拼音) in 2002 (Hughes 2011). This move was aimed at institutionalizing Taiwanese native dialects as national languages alongside Mandarin, thereby empowering “the people” by affirming their unique linguistic heritage and embedding a narrative of us (Taiwan) and them (mainland China) (Hughes 2011).

Fourth, the Taiwan-centric cultural identity continued spreading as Tsai Ing-wen won the 2016 election, Taiwan-centrism having served as the cornerstone of her populist appeal. She repealed the KMT’s 2014 curriculum changes increasing ancient Chinese literature and, by 2018, her government had released a new history curriculum heavily trimming Chinese content and recategorizing it under an East Asian chapter. This trend toward cultural exclusion of Chinese and a reconsolidation of Taiwanese subjectivity served a populist purpose: framing Taiwanese culture as having been colonized by Chinese culture, thus defining a pure Taiwanese identity in need of defense (Shih 2021). This discursive practice created a “people” versus “excluded others” dichotomy, linking Taiwan’s cultural subjectivity to national dignity by positioning Taiwanese as an innocent group that had been subjected to an external Chinese cultural invasion, and thereby recontextualizing “the people” within a populist framework (Sullivan and Lee 2021).

Conclusion

I identified two dimensions contributing to populism’s rise in Taiwan: economic anxiety and cultural backlash. Economic anxiety is exacerbated by public insecurity and dependence on mainland China’s market. Cultural backlash stems from historical resistance against external forces and the consolidation of civic nationalism, evolving into a populist antagonism between Taiwanese and Chinese.

By synthesizing Taiwan-related literature, I revealed the characteristics and dynamics of populism’s interaction with Taiwanese society. Building on these insights, I proposed an economic-cultural framework (moderate, economic, cultural, and intense populism) for a more comprehensive analysis of Taiwan’s populist phenomenon.

Although I argue that economic anxiety and cultural backlash are compatible with Taiwan’s populism, it should be clarified that political actors can address these issues without using populism. For example, the TPP has emphasized addressing voters’ economic anxieties, including pension, labour, and youth issues (C. Wu and Chu 2021), while so far no literature has identified populist discourse linked to their addressing these anxieties. Hence, it is necessary to identify populist messages first, before following up by using the economic-cultural framework for analysis.

Populism renders political arguments compelling through economic and cultural dimensions in Taiwan. Han Kuo-yu’s success exemplified this: He leveraged anti-elitist populism, sensationalizing economic anxiety on the demand-side in the south and simply attributing economic problems to the DPP, thereby successfully challenging the DPP’s 2018 Kaohsiung stronghold (Krumbein 2023). Such populist messages thrive on social media, with Facebook being a key battleground in Taiwan’s elections. Therefore, Taiwan’s public sphere, especially its election campaigns, is most likely to face a prisoner’s dilemma: Political parties and actors are incentivized to adopt similar populist strategies to avoid electoral disadvantage, especially following Han Kuo-yu’s success story.