Introduction

The status quo established between Beijing and Taipei in 1949 is becoming increasingly polarized around two antipodal outcomes, reunification[1] and a de facto, or de jure, independence, and a peaceful conclusion to this conflict seems, nowadays, very unlikely (Bosco 2014; Schreer 2017).

What we will name “the status quo’s crisis” between China and Taiwan is a subject of paramount importance for world peace (Lieberthal 2005). The status quo’s crisis can be explained through various factors, such as the weakening deterrent power exercised by the United States over Beijing (Xiying 2021; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021), which is emphasized by the rise of China as a superpower and status quo challenger (Wortzel 2013; Kong 2015; Yu 2017; Xiying 2021), as well as the important role that Taiwan plays in the maintenance of the East Asia regional balance of power (Benson and Niou 2001; Brookes 2003; Sacks and Hillman 2021; Sacks 2022). In addition, the increasingly important role that Taiwanese identity is playing in Taiwan society (Zhong 2016; Zhu 2017), coupled with the continuation of the status quo (Goldstein 2002; C.-H. Huang and James 2014), are contributing to an increasing irreconcilability between the two sides’ favored endings and are making a potential peaceful unification a gradually less likely option (Bosco 2014; Schreer 2017). Therefore, in its current situation, the status quo represents a deadlock (Goldstein 2002), which is clashing with Beijing’s plans, under which reunification is seen as inevitable (Schreer 2017; Mastro 2021).

Despite the several attempts by China to bring Taiwan closer to reunification (Ross 2000; C.-C. Chang and Yang 2020; C.-J. J. Chen and Zheng 2022), the status quo has been facing for the last three decades tremendous changes (Bosco 2014; Zhao 2015; Schreer 2017)) that have undermined its already insecure functioning.

All of this led us to think of our research question as follows: For which reasons may the status quo between China and Taiwan no longer be sustainable in its current sociopolitical context?

Literature review

Shaping the status quo according to national interests is what motivates the actions of the parties involved (Benson and Niou 2001; R. Bush 2019; Mastro 2021). The potential resolution of the status quo is part of a power struggle between the United States and the PRC. Taiwan represents a key issue for stability in the Asia-Pacific region (Zhong 2016), in which China is advancing its territorial claims in the East and South China Seas (Zhao 2015). The island represents a major stake and a perpetual source of discord between Washington and Beijing (Xiying 2021; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021).

The literature has examined the preferences concerning the resolution of the status quo that are pursued by the different actors concerned (Goldstein 2002; E. M. S. Niou 2004; C.-H. Huang and James 2014), and the conclusion is that they totally differ (Zhong 2016; Schreer 2017). Therefore, this lack of consensus concerning how to resolve the conflict has placed the status quo in a deadlock (Goldstein 2002). Various elements, such as the Chinese use of military power (Goldstein 2002; Schreer 2017; U-Jin and Suorsa 2021b), juridical threat (Tan 2014), economic (Breuer 2017) and diplomatic (S. T. Lee 2023) pressure, as well as a growing Taiwanese national identity (Zhong 2016; Zhu 2017) and Taiwanese aversion to reunification (Gang 2007; R. Bush 2019), are undermining the possibility of finding a peaceful solution.

The literature concerning the relations between Taiwan and China, although vast, does not particularly consider how the constant evolution of the status quo has been a critical component of the explanation for the growing conflict in the Strait. The studies focusing on the status quo and the elements which have influenced it are quite rare and outdated as they do not examine recent, and important, changes that have occurred in the last decades.

The status quo’s definition

To assess if the current status quo between China and Taiwan may no longer be viable in the current sociopolitical context, it is firstly necessary to frame and define the status quo.

Although the earliest years of the status quo embody events that strongly changed cross-strait relations, we argue that Taiwan’s democratization and the 1992 consensus have led to the modern status quo by irremediably shaping cross-strait relations.

The earliest years of the status quo were particularly marked by the first two Taiwan Strait crises (Halperin 1966; H.-T. Lin 2013), in 1954 and 1958, by few contacts, narrow trade, no diplomatic ties and by both the ROC and the PRC each emphasizing that their government was the official representative of all Chinese people (Albert 2016). In 1971, United Nations resolution 2758 gave the U.N. Chinese seat to Beijing and started a long struggle for international recognition for Taipei (Maggiorelli 2019). That resolution would soon be followed by the three U.S.-PRC Joint Communiqués, in 1972, 1978 and 1982, which led to Washington’s “One China” policy, acknowledging that there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China, and to the recognition of the Government in Beijing as the sole legal Government of China.[2] Nonetheless, in 1979, the 1954 Taiwan-U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty was replaced by the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA) (Turin 2010). This Act granted Taiwan defensive weapons based on Washington’s judgment of Taipei’s needs.[3] In addition, the TRA created an “unofficial embassy,” named the American Institute in Taiwan, which acts as an embassy to maintain de facto diplomatic relations between both parties (Turin 2010). The TRA has been accompanied by the “Six Assurances”[4] in 1982, establishing the foundations of the U.S. commitment toward Taiwan.

The current sociopolitical form of status quo began, in our opinion, in the mid-1980s, when the Kuomintang authoritarian regime started to open its political system by granting legal status to opposition parties (S.-Y. Tang and Tang 1997), resulting in the creation of the Democratic Progressive Party (Albert 2016), and later by giving up martial law in 1987 (S.-Y. Tang and Tang 1997). In addition, numerous restrictions concerning public rallies, travel to the mainland and mass media were lifted (H.-M. Tien and Shiau 1992). A second wave of democratization took place when the Temporary Provisions, which guaranteed unlimited power to the president of the ROC, were suspended (H.-M. Tien and Shiau 1992) and with the start of open elections of the National Assembly in 1991 and the Parliament (Legislative Yuan) in 1992 (S.-Y. Tang and Tang 1997). Taiwanese democratization was eventually completed in March 1996 when the direct election of the first Taiwanese President, Lee Teng-hui, took place, marking the final chapter of Taiwan’s institutional democratization (H. M. Tien and Chu 1996; R. Bush and Rigger 2019).

Taiwanese democratization resulted in four major changes that irremediably shaped the status quo. Firstly, democratization is closely related to the “taiwanization phenomenon” (E. M. S. Niou 2004; Hughes 2011; Jacobs 2013), which corresponds to a growing Taiwanese identification as a proper population that is explicitly not Chinese (Jacobs 2013). Secondly, Taiwan’s democratization increased support and sympathy from Americans and raised the cost for the latter to withdraw from the island (R. Bush and Rigger 2019). Thirdly, democratization impacted the established status quo by offering to the Taiwanese a way to influence cross-strait relations. Following democratization, Beijing lost its option of making deals with a small part of the KMT leadership who had been empowered to take decisions for the entirety of the island (R. Bush and Rigger 2019), and the unification must now be endorsed by Taiwanese (R. C. Bush 2017). Finally, democratization also increased cross-strait tensions. The third and last Taiwan Strait crisis started in 1995 because of China’s worries concerning potential Taiwanese independence while Taipei was worried because Beijing was successfully making the island dependent on the mainland (Turin 2010). This new strait crisis resulted in a long period of tension between China and Taiwan (Turin 2010), which was then exacerbated by Chen Shui-bian’s election in 2000 (E. M. S. Niou 2004). Democratization marked a rupture between the ROC and the PRC concerning their political structure, their identity and their position concerning unification.

Additionally, in 1992 a meeting took place between the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Strait (ARATS) of the PRC and the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) of the ROC to talk about the “One China” principle, resulting in the “1992 consensus.” According to the PRC’s government, there is only one China, and Taiwan is a part of China (Xu 2001). For the ROC, the 1992 consensus signifies that there is only one China, but Taipei and Beijing disagree on which government is its legitimate representative (J. Huang 2017). This consensus has been the basis of cross-strait relations (J. Huang 2017) and a matter of national dispute in Taiwan (Schubert 2004). The “One China” principle has been used as a tool, by the mainland, to contain Taiwanese independence claims and potential action with the aim of preserving peace in the Strait and gaining time to achieve, one day, the overcoming of the deadlock of the status quo (Xu 2001). The 1992 consensus was therefore a way to end the status quo in the long term by resuming the dialogue between both parties, thus hoping to reach a peaceful solution for unification. It established a shared political framework. The consensus was designed to deter Taiwanese independence and warn that any failure to commit to the “One China” essence of the 1992 consensus would result in the breakdown of political trust and would consequently reawaken the conflict (Romberg 2016). The narrative of a political “consensus” is stressed by Beijing with the aim of emphasizing that this consensus embodies its “One China” principle and that therefore Taiwan has agreed to being a part of the mainland (Y.-J. Chen and Cohen 2019).

These two major events in the history of the Strait established the current status quo. The introduction of democracy in Taiwan increased the political cleavage between the two sides of the Strait, promoted the rise of a Taiwanese identity and strengthened the relationship between Taipei and Washington. The 1992 consensus created the political framework necessary to resume talks between the ROC and the PRC and continues to represent, nowadays, a very salient subject in cross-strait relations.

The status quo, as we define it, is a situation of neither peace nor war, portrayed as a deadlock, in which neither a peaceful unification nor independence are achievable. It refers to a democratic Taiwan, in which the Taiwanese identity is spreading and where Taiwanese can influence cross-strait relations, and a China that tried for a long time to slowly absorb the ROC to facilitate reunification. Additionally, the United States is part of the equation by providing weapons and support to Taiwan, while trying to reduce the expansion of Chinese power.

This structure has been sustained by several factors that currently do not ensure anymore the sustainability of the status quo.

The end of the status quo

Increased power imbalance in the Strait

The first factor in the growing instability in the status quo is the evolution of China’s power. The power preponderance of Washington allowed it to deter both China and Taiwan and helped maintain the status quo (Gordon 1985; Turin 2010; H.-T. Lin 2013; R. Bush and Rigger 2019). The ability of the United States to deter both the ROC and the PRC was the result of its economic, political and military supremacy in the East Asia region coupled with its strategic ambiguity (Benson and Niou 2001; Turin 2010; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021). Indeed, the U.S. was, during a long period of the status quo, militarily stronger (Halperin 1966; Turin 2010), economically more developed and capable (Xiying 2021) and politically more influential (Goldstein 2002) than both Beijing and Taipei. Consequently, Washington was able to shape the status quo over a long time because neither side of the Strait was a concrete threat to the U.S.'s policies (Xiying 2021). Thanks to strategic ambiguity, Washington has been able to deter both sides from taking unilateral decisions and risking a test of Washington’s commitment in the dispute (Benson and Niou 2001).

Moreover, the United States has tried to avoid taking sides in the Taiwan question while trying to maintain good relations with Beijing and Taipei (Saunders 2005). Washington has worked on the establishment of a stable security situation with the aim of allowing Taiwan to negotiate in a position equal to the PRC and has emphasized that it will accept any outcomes that fulfill, peacefully, the two sides’ objectives (Goldstein 2002; Saunders 2005).

However, China has nowadays become a great power and a challenger for the United States (Kugler and Organski 1989). The “rise of China” has been made possible thanks to numerous policies pursued by Beijing. China implemented the liberalization of its economy, focused on its exports and benefited from its low-cost labor force to further develop the country (Paul 2016). Chinese economic development allowed the PRC firstly to increase the gap with Taiwan and secondly to get closer to the USA in terms of being the most dominant nation (Xiying 2021). This rise also occurred thanks to its increasingly stronger military capability and power. Indeed, China now possesses the second largest military budget in the world (Blackwill and Zelikow 2021), the largest navy in the world and one of the largest surface-to-air systems.[5] This enormous military power not only represents a strong instrument in case of war but also constitutes a powerful tool for bargaining and foreign policy concerns (Wortzel 2013).

The “rise of China” possesses serious implications for the status quo and its continuation over time. As stated by Xiying (2021), China’s economic and military rise have profoundly transformed the deterrence dynamic in the Taiwan Strait. In fact, the increased power of the mainland has undermined the deterrent power of the United States and the latter’s faculty to dissuade China from pursuing a more coercive posture towards Taiwan and unification (Xiying 2021). The relatively weak stability in the Strait was the result of the fact that China and the U.S. kept a delicate balance between coercive threat and reassurances to each other (Christensen 2002). The rise of China resulted in the fact that the Taiwan question no longer corresponds to an asymmetrical confrontation. China has the strategic goal of undermining the bases of the American posture in Asia and asserting its own position as a global leader in a more proactive way (Kong 2015; Yu 2017) in order to fulfill its aspiration to alter the established status quo in the Asia-Pacific region (Zhao 2015). Consequently, the PRC is becoming less reassuring towards the U.S. concerning peaceful reunification, while Washington is becoming less capable of effectively threatening Beijing when the latter does not respect the status quo (Xiying 2021).

Nevertheless, the numerous unilateral actions undertaken by China during the last years (Schreer 2017; M. M. Tsai and Huang 2017; R. Bush 2019) have faced economic, diplomatic and military opposition from Washington (Xiying 2021). The United States cannot let the PRC act freely concerning Taiwan because that would be an admission of weakness (Benson and Niou 2001; Brookes 2003). The U.S. guarantees concerning Taiwan’s defense also serve to limit the Chinese threat affecting other Washington allies, such as Japan and the Philippines (Sacks 2022). If the U.S. commitment towards Taipei is too low, China might resolve to use force to compel Taiwan to accept unification (E. Niou 2008).

The U.S.-China rivalry thus materializes in the question of Taiwan and destabilizes the status quo. The lack of consensus between Beijing and Washington on the matter of Taiwan pushes both sides to adopt preventive policies. The changes in the power balance in the Strait have undermined the ties between Washington and Beijing (Xiying 2021; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021). The shift in the power distribution has raised concerns about the fact that China will rapidly possess the ability to invade Taiwan to compel the latter into unification (Sacks 2022). China’s military modernization programs have been driven by the desire to improve the PLA’s capabilities for a Taiwan contingency (Schreer 2017), notably following the failures that the PRC faced when it attempted to positively convert its influence over the island into impetus for reunification (Muyard 2012; Schreer 2017).

Xi Jinping, the rise of the People’s Liberation Army and its use to influence the status quo

A “peaceful” unification

Indeed, China initially took the decision to pursue a more “peaceful” path to achieve the much-desired reunification. Although the People’s Liberation Army has been used as a coercive and bargaining tool over time in different national issues (Hui 2020; Gupta 2020), the Central Government opted, in part, to use other instruments to assert its leverage over Taiwan and therefore push Taipei to accept reunification (Breuer 2017; Tuman and Shirali 2017). By deciding to not take arms to force unification, China contributed to maintaining the status quo by not drastically and suddenly upsetting it. Although the reason for not attacking Taiwan directly was influenced by the fact that the PLA was weaker than the U.S.'s military capabilities, China also decided that the best way to achieve reunification was to bring Taiwan closer, economically and politically, to the mainland.

Taiwan’s economy is strongly dependent on its trade with the mainland. China is Taiwan’s major export and import market, accounting for approximatively 40 and 20 percent, respectively (C.-J. J. Chen and Zheng 2022). In addition to these strong trade relations, numerous Taiwanese work in the mainland (C.-J. J. Chen and Zheng 2022). This strong economic interaction underpins the work and lives of many Taiwanese, which might affect their attitude towards Beijing in a more positive way (C.-J. J. Chen and Zheng 2022). The development of dependent economic relations between the two sides of the Strait has been used as a tool to integrate Taiwan to the mainland to facilitate reunification (C.-J. J. Chen and Zheng 2022). Cross-strait economic ties strengthened social connections because of the need for cooperation and coordination (Wu 2005). They resulted, in the early 2000s, in an increasing proportion of Taiwanese, who had experienced visits to, investment in or work on the mainland, identifying themselves as Chinese (Wu 2005). However, this trend has been largely crushed by the growth of Taiwanese identity, although it has at least slowed the latter down (Wu 2005). Ross (2000) asserted that China expected that economic collaboration would make Taiwan increasingly dependent on the Chinese economy and that, in conjunction with deterrence, diplomacy and time, China would have been able to absorb Taipei into the mainland. These close economic ties have been used by China with the aim of influencing Taiwanese public opinion by expanding China’s sphere of influence inside Taiwan’s borders (C.-C. Chang and Yang 2020).

In addition, the growing dependence of Taiwan’s economy on its trade relationship with China resulted in a weakening of its economic ties with others among its major partners. In fact, Taiwan’s exports to the United States, Europe and Japan, as shares of its total exports, declined considerably, making Beijing Taiwan’s most important economic partner (Chiang and Gerbier 2013). However, this trend has been recently reversed, and the U.S. has become the main destination for Taiwan’s exports in the first quarter of 2024.[6] China pursued an asymmetrical economic relationship with Taiwan to create dependence and political dominance (C.-C. Chang and Yang 2020) and an ability to use its economic power as a coercive instrument to reach reunification, or at least to deter an independence claim by Taipei (Schreer 2017). Coercive use of economic relations has taken the form of a blockade of tourism to Taiwan from China, boycotts of Taiwanese firms established on the mainland, the creation of import standards to ban Taiwanese products and illegal or forced buyout of Taiwanese companies (C.-C. Chang and Yang 2020).

Taiwan’s international isolation

Moreover, China has limited Taiwan’s international implication by blocking its participation in international organizations (C.-J. J. Chen and Zheng 2022) and by trying to make it lose its precious political allies (Breuer 2017; Tuman and Shirali 2017; Mastro 2021). Beijing has aimed to isolate Taiwan from the United States (Goldstein 2002) while reducing Washington’s participation in cross-strait relations to strengthen China’s power over Taiwan (J. Huang 2017).

However, China has struggled to convert its economic and diplomatic leverage into Taiwanese support for reunification. On the island, fears arise concerning not being able to break away from the grip of Beijing because of the increasing economic dependence on the mainland (Albert 2016). Notably, in 2014, the growing displeasure of the Taiwanese people erupted into the Sunflower Movement, which was opposed to the increasing cross-strait economic integration (C.-H. Huang and James 2014) and especially a free trade agreement with China, which never came to fruition (Blackwill and Zelikow 2021).

The PLA and the new Chinese approach

Facing these failures, the mainland has opted for a more coercive stance, thus changing its long-term strategy to a more direct, and destabilizing, posture. Reunification by peaceful means and economic coercion failed to bring Taiwan closer to the mainland (Muyard 2012; Schreer 2017). Consequently, the recently acquired military capacity and its strong economy offer to the PRC the opportunity to renegotiate the terms of the Taiwan question and to change its strategy to achieve reunification.

The heart of this change in strategy lies in the new place that the People’s Liberation Army occupies in the policy of reunification. Indeed, Xi Jinping has broken with the former policy, which aimed to slowly absorb Taiwan into the mainland (Ross 2000), in favor of increased use of the PLA (Blackwill and Zelikow 2021). This translates into an enlarged involvement of military means in the way the status quo is apprehended by China (Mastro 2021). Xi Jinping represents a turning point in the way China perceived the status quo. The General Secretary wants to resolve the Taiwan question in a much shorter time frame than his predecessors and has consequently taken a more aggressive stance on issues of sovereignty (Mastro 2021). Under Xi Jinping’s presidency, the estimated Chinese military expenditure has grown from 165,824 million USD in 2012 to 309,484 million USD in 2023.[7] This massive increase in military expenditure is correlated with Xi Jinping’s risk-seeking character (Sacks 2022). The increasing power of the PLA makes China more confident to explicitly compete with its direct neighbors and Washington (Thompson 2020; U-Jin and Suorsa 2021b, 2021a).

While the General Secretary is not giving up using more peaceful tools to bring Taiwan closer (Mastro 2021), the inclusion of the PLA in the status quo equation completely upsets the way it is managed. The biggest fear is not anymore that Taiwan could unilaterally declare independence but rather that the PRC could resolve to use force to achieve unification (Xiying 2021). The direct consequence of the rise of China and its increased use of military power is that there is a risk that the CCP will become increasingly unwilling to back down or compromise in the face of conflicts (Thompson 2020). Hence, Taiwan-China relations have reached a new period of uncertainty (Schreer 2017). The PLA offers to the PRC a way to circumvent a peaceful unification.

Chinese coercive power, although effective in deterring Taiwan from seeking de jure independence, also generates a backlash from Taiwanese who refuse to submit to conditions that do not suit them (Schreer 2017). The risk here is that China, tired of waiting for Taiwan to accept reunification, will unilaterally act to compel the island to accept being unified.

However, this growing instability in the status quo is caused not only by Chinese actions but also by sociopolitical factors in Taiwan. To understand why China might resolve to use its military force to compel Taiwan into unification, it is necessary to consider for which reasons peaceful unification seems, nowadays, to be utopian.

Tsai Ing-wen, her refusal to endorse the 1992 consensus and the pursuit of her policy position by Lai Ching-te

Although Xi Jinping’s accession to leadership of the Chinese Communist Party has been a turning point in the way the status quo and reunification are perceived in the mainland, the accession of Tsai Ing-wen as President of Taiwan has also been a tremendous earthquake for the status quo. Indeed, President Tsai abruptly broke with the manner cross-strait relations had been handled under Ma’s administration (Y.-J. Chen and Cohen 2020; Maizland 2024) by relegating the 1992 consensus to the status of “historical fact”[8] and not endorsing it (Y.-J. Chen and Cohen 2020). President Tsai refused to adhere to the Chinese principle that considered Taiwan to be part of the sovereign territory of the PRC (R. Bush and Rigger 2019). This non-endorsement of the 1992 consensus triggered a complete and violent upheaval of the status quo and the way it had evolved over the previous eight years. Tsai’s election represented, for Beijing, the repudiation of an entire decade of patient policy (R. Bush 2019).

Tsai’s actions resonated, in Beijing, as an attempt to refuse to give guarantees concerning a potential formal independence (Romberg 2017). However, the former President was careful to not declare independence and chose instead to stress Taiwanese public opinion while urging the PRC to accept Taiwan’s democracy (Xiying 2021). Tsai, often, resisted pressure from pro-independence elements, both inside and outside the DPP, which clamored for more symbolic initiatives concerning independence (R. Bush 2019; R. Bush and Rigger 2019). Tsai’s election resulted in a change in Beijing’s policy towards Taiwan, which shifted from a reactive response to an active shaping of the Taiwanese trend towards independence, notably through pushing several nations to cut diplomatic ties with the island (Xiying 2021).

China increased its bellicose behavior and used coercive military and economic means (Tuman and Shirali 2017; Schreer 2017; S. T. Lee 2023) to force the head of the island’s government to accept the 1992 consensus while extensively working to further isolate Taiwan from the international system (Blackwill and Zelikow 2021). However, this more coercive posture pursued by China is not advancing unification and, on the contrary, is driving away, politically and culturally, the island from the mainland (Schreer 2017; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021). Tsai’s elections marked a change in the status quo paradigm by emphasizing an increasing political and cultural discrepancy between an authoritarian China and the confirmed democracy that Taiwan has become.

Tsai Ing-wen’s refusal to recognize the 1992 consensus and her opposition to having closer ties with Beijing would not have been possible in a context in which the Taiwanese people were in favor of unification. When Tsai reached office in 2016, anti-mainland feeling was growing in Taiwan (Blackwill and Zelikow 2021). Her reelection in 2020 attested to the Taiwanese desire to pursue this policy of vigilant relations with the mainland (Mastro 2021).

The recent election of Lai Ching-te as the new president of the ROC follows this trend of general distrust toward the CCP. Lai is expected to represent continuity with the two preceding mandates. The new Taiwan President has already pledged that Taiwan would maintain the cross-strait policies and positions pursued by former president Tsai (Keegan and Churchman 2024). Lai has publicly criticized the 1992 consensus, advocated for Taiwanese sovereignty as a mandatory step toward peace with the PRC and pledged the strengthening of Taiwan’s military capacities (Fell 2024).

Nonetheless, Taiwan’s 2024 election saw the emergence of a new political force, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP). The TPP is opposed to Taiwan’s independence and does not endorse the 1992 consensus.[9] Ko Wen-je, the party leader, has advocated for “Taiwan’s Sovereignty, Cross-Strait Peace,” by endorsing a change in how the cross-strait policies are being handled.[10] From its standpoint, the DPP is being too provocative toward China while the KMT is seen as too weak toward the mainland (Yoshiyuki 2024). In a context of political fragmentation (R. C. Bush et al. 2024), where neither the DPP nor the KMT have been able to secure a majority in the Legislative Yuan,[11] the TPP will play an essential role in Taiwan’s political system and will benefit from a strong bargaining position (R. C. Bush et al. 2024). Although the election of Lai Ching-te represents a choice by the Taiwanese, who decided to pursue the policies and stances towards China built by Tsai Ing-wen since 2016, the election results show that President Lai won with only 40.05% of the vote, the lowest percentage since Chen Shui-bian in 2000,[12] and that the DPP failed to retain a majority in the Legislative Yuan (Rigger 2024). The emergence of the TPP as a major political actor not only represents a potential change in the political system but could also possess deep implications for one of the most important factors in the evolution of the status quo, which is Taiwanese identity.

The fight against time: The Taiwanese identity

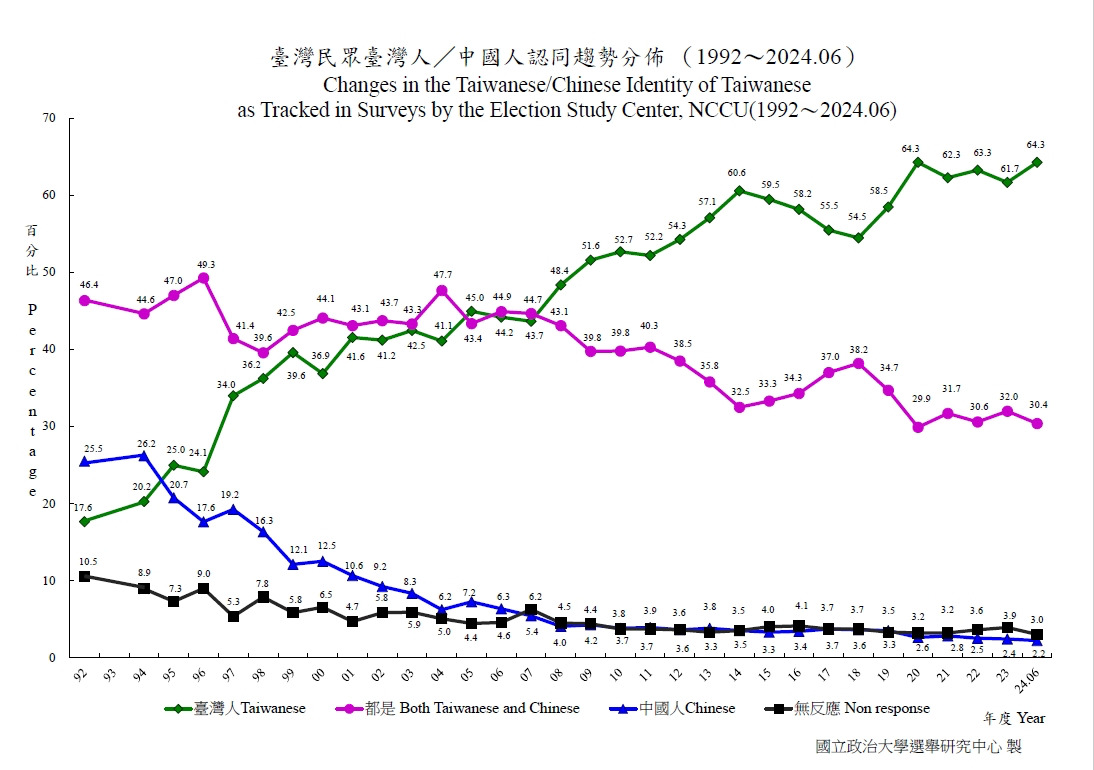

National identity arises from individuals’ mutual characteristics, such as the language and the culture, and a common goal (M. Chang 2003; Dittmer 2004). The development of democracy in Taiwan contributed to the rise of a national identity on the island centered on the concept of “Taiwanese” (Zhong 2016; Zhu 2017) and initiated a “de-sinicization” process (Hughes 2011). The Taiwanese identity possesses deep implications for the status quo because it plays a central role in the independence movement in Taiwan. Indeed, fewer and fewer individuals in Taiwan identify themselves as “Chinese” (Zhong 2016; Election Study Center, National Chengchi University 2024[13]). In 1992, only 17.6% of Taiwanese perceived themselves as exclusively Taiwanese, and 25.5% defined themselves as solely Chinese. In 2024, 64.3% of the population described themselves as Taiwanese, while 2.2% defined themselves as Chinese.[14]

The notion of a national identity forms the idea of “self,” which opposes the concept of “other” (Zhong 2016). Although the identity shift that has occurred concerns principally the political aspect of their identity and not the ethno-cultural one (Zhong 2016; Rigger et al. 2022), this distinction between the “self” and the “other” represents a major issue in the conception of a peaceful unification. Indeed, how can the goal of reunification be achieved with a population, and a nation, which does not consider itself a part of this union? The constant importance that Taiwanese identity is taking on the island raises Chinese worries about the prospects for a pacific unification in the future (Zhong 2016).

Taiwanese identity is deeply bonded to its democracy (Zhong 2016; Zhu 2017). Taiwanese democracy represents a separation from the Chinese political framework and generates, consequently, an identity demarcation (E. M. S. Niou 2004). Democracy has contributed to the separation from authoritarian China, the “other,” and the democratic island, the “self” (S. S. Lin 2021). Democracy is therefore constitutive of the Taiwanese identity (Rigger et al. 2022) and influences it by spreading norms and values that are not shared with China. Freedom, high degree of autonomy and civic values are factors strongly endorsed by Taiwanese when describing what constitutes their identity (S. S. Lin 2021). Consequently, they prefer a sociopolitical future in which these values and norms are ensured (S. S. Lin 2021).

Additionally, the younger Taiwanese are the part of the population who identify themselves as “only Taiwanese” the most and “only Chinese” the least, as well as being the demographic category most supportive of independence and the lowest supporters of an immediate or eventual unification (B. Lin 2021). This is particularly interesting when juxtaposed with the rise of the TPP. The Taiwan People’s Party has been strongly supported by the young electorate (Rigger 2024), despite its pan-blue leanings (Hioe 2024), and Ko, the TPP’s presidential candidate in the last election, also attracted nonpartisan voters (Yoshiyuki 2024). In their research. C. Tsai, Johnston, and Yin (2024) highlighted how the nonpartisan and TPP voters were more inclined to align with China concerning the national security and economic development of the island. The authors underlined how this alignment toward China was positively influenced by the unification stance, the perception of China’s influence and Chinese cultural similarities and that possessing an exclusively Taiwanese identity had the opposite effect (C. Tsai, Johnston, and Yin 2024). Consequently, the rise of the TPP could result in changes concerning the progression of Taiwanese identity.

The last election showed that the notion of identity is becoming less salient in the political debates and that the DPP has been less able to mobilize it to generate reaction from the voters (Yoshiyuki 2024). Nonetheless, the DPP remains the political entity with the largest party identification among Taiwanese.[15] In addition, the TPP is currently plagued by corruption scandals, and its popularity is decreasing, which may affect its future (Sacks 2024). Moreover, a more coercive and aggressive China concerning unification could result in a reinforcement of identity, as happened during the sunflower and umbrella movements or the more recent protests in Hong Kong (Yoshiyuki 2024). Finally, the figure reproduced above from the survey conducted by the Election Study Center demonstrates that Taiwanese identity continues to rise.

The more time advances, the more future generations are unlikely to support unification. This finding highlights two connected issues for the status quo’s stability. Firstly, China can no longer afford to wait, slowly absorbing Taiwan, because it does not work (Muyard 2012; Schreer 2017), with time reinforcing the identity opposition between the two countries (Rigger et al. 2022). Secondly, the increasing part of the population that describes itself as only “Taiwanese” is more prone to be opposed to unification, thus totally undermining the hope for China to be able to peacefully reintegrate Taiwan into the mainland.

Taiwanese identity does not correspond to a total rejection of Chinese culture, but rather to the rejection of the PRC because of political and civic factors (Zhong 2016; S. S. Lin 2021; Rigger et al. 2022). Thus, the rejection of unification is driven by political factors and not cultural ones (Zhong 2016; Rigger et al. 2022). Facing Beijing’s coercive attitude and action towards Taipei, Taiwanese will be driven away from wanting to identify themselves as Chinese, thus making cross-strait relations even more difficult (Rigger et al. 2022) and undermining the stability of the status quo. The more time passes, the more China will face an identity bloc that is hostile to it. In addition, time is also favorable to the Taiwanese for the autonomy it guarantees them.

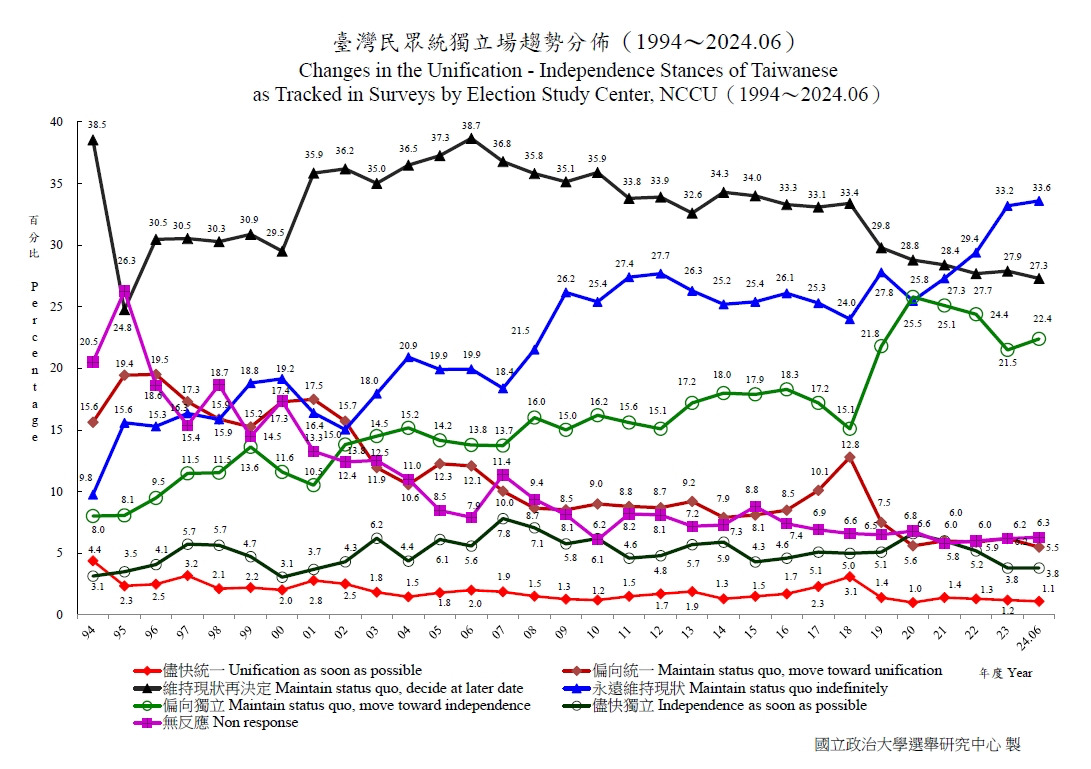

The status quo as a soft form of independence … and a potential trigger for war

An independence move from Taiwan would inevitably trigger an armed reaction from China. Facing this reality, it is not surprising that most Taiwanese are opposed to a declaration of independence if it would result in an attack by China, especially because roughly 57% of Taiwanese think that Taiwan could not defend itself if China struck (Hickey 2020). While a large majority of Taiwanese are opposed to unification, immediately or later, support for immediate independence is still low, at 3.8 percent, and most Taiwanese support the status quo in a shorter time frame, but also indefinitely.[16]

Preferences concerning the future development of the status quo are, in part, conditioned by the commitment of the United States to defend Taiwan. The strategic ambiguity pursued by the United States contributes to making Taiwanese less inclined to push towards de jure independence (Wang et al. 2024). This is also true concerning dual clarity, in which Washington would commit to defend Taiwan in case of invasion from China if Taipei promises to never unilaterally declare de jure independence (Wang et al. 2024). In contrast, strategic clarity, in which the U.S. would unconditionally defend Taiwan in the face of a Chinese attack, raises the level of support from Taiwanese concerning independence (Wang et al. 2024). Taiwanese know that their security depends on their respecting the U.S.'s established rules concerning the status quo, which knowledge directly affects national support for de jure independence.

Eighty-three percent of Taiwanese favor the continuation of the status quo,[17] and nearly 75% of Taiwanese think that Taiwan is already an independent country (Hickey 2020). In this context, the status quo is consequently seen as a form of “soft independence” because, from the Taiwanese perspective, Taiwan and China are already two separate entities (Zhong 2016), and the status quo has allowed Taipei to thrive as an established democracy and important economic player. The status quo grants Taiwan political autonomy and an international personality, which, although limited, contributes to its sovereignty and allows the ROC to not be assimilated into the PRC political system (Rigger 2001). The status quo has permitted Taiwan to become a key actor in global technology supply chains, especially semiconductors (Sacks and Hillman 2021), making Taiwan indispensable for almost every advanced civilian and military technology (Y. Lee, Shirouzu, and Lague 2021) and one of the most important nodes in the global economy as a major supplier of goods and holder of foreign exchange reserves.[18] The status quo is a de facto independence for Taiwan (C.-H. Huang and James 2014), and the more time goes by, the more this independence will be reinforced.

Consequently, the existence of the status quo itself has become harmful to its persistence. The continuation of the status quo implies that Beijing’s range of action and time to act will become increasingly narrow since Taiwan will advance further in its identity and in its de facto independence. Hence, the perpetuation of the status quo carries the risk that China will become gradually more aggressive towards Taiwan to compel it to accept reunification. The PRC has already taken steps to oppose these trends in Taiwan, especially with the Anti-Secession Law (ASL),[19] the content of which resonates as a tool to counter the current direction taken by the status quo. As stated by M. M. Tsai and Huang (2017), with the Anti-Secession Law, China has built a legal justification to use force against Taiwan. The ASL offers to the CCP the judgment of when diplomatic means will be exhausted and non-peaceful ones will be needed (R. Bush 2019). The Anti-Secession Law is an open threat directed toward Taiwan (Tan 2014) and shows that the status quo is not sustainable in the long term (Bosco 2014). By using the ASL as a pressure tool, the PRC is employing the “carrot and stick,” by stressing to Taiwan that it must accept a peaceful unification to avoid an armed conflict.

Consequently, the status quo is subject to a countdown, at the end of which China will not accept it anymore and will, therefore, act. The relatively widespread support for the status quo in Taiwan is confronted with the need for immediate action from the perspective of Beijing, for whom the time factor is becoming increasingly dangerous. The rise of the PLA offers to the CCP a new way to influence the status quo and to circumvent Washington’s deterrence. In this context, is the status quo between China and Taiwan still viable?

Conclusion

As discussed above, reunification is not an appealing option for Taiwan. On the other side of the Strait, China’s economic coercion did not work in bringing Taiwan closer (Muyard 2012; Schreer 2017), and consequently China has adapted its strategy towards Taiwan via a stronger implication of the PLA. The continuation of the status quo is not an option for the PRC, for which reunification is the uniquely acceptable outcome. The desired ending as well as the relationship to the status quo differs in the extreme between the two polities, and finding a mutual agreement is very unlikely to happen. The longer the status quo lasts, the worse the relationship between the two sides will be. Hence, the evolution of the status quo is rather worrying. China is strongly dissatisfied with how the status quo is progressing. Because of its increasing military, political and economic power and because of the weakening of Washington’s deterrence, its military reaction to resolve on its own terms the status quo is growing as a concrete possibility.

Consequently, what may be the future of the status quo? Currently, there are three major potential scenarios. The first one is unification. It seems completely unlikely that a peaceful unification could still be achieved. Without a total, and surprising, turnaround from the Taiwanese political class and population, peaceful reunification is a very unlikely development. Taiwanese identity and the generalized sentiment of being a sovereign state are obstacles that cannot be overcome (R. Bush and Rigger 2019) and increase China’s sense of urgency regarding Taiwan (Cozad 2021). Henceforth, unification could only be achieved by non-peaceful means. Although an invasion of Taiwan may not be imminent (R. Bush 2019; Mastro 2021), the risk of conflict in the Strait is now at its highest level in decades (Y. Lee, Shirouzu, and Lague 2021; Xiying 2021; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021), and no option can be excluded. China’s dissatisfaction with the current status quo will only get worse with time, and a direct use of force against the island will become the unique option for the achievement of reunification.

The second scenario corresponds to a separation, peaceful or not. In this case also, this development seems impossible to realize. A peaceful separation is not consistent with Beijing’s posture concerning the resolution of the status quo. The Chinese Central Government has stated many times its unshakable commitment concerning reunification, and its actions since the beginning of the status quo do not show that China considers, or would consider, the option of Taiwan’s becoming a de jure independent country. The weak support for immediate independence signaled by the Taiwanese and the preference for the continuation of the status quo, coupled with the successful deterrent of Chinese power, make non-peaceful separation a very unlikely evolution, too.

That leaves us with the last scenario, that is, simply the continuation of the status quo. Because of the divergences and the irreconcilable paths that Taipei and Beijing are following, there is currently no other solution than preserving the actual status quo. However, that does not mean that the continuation of the status quo is a functional scenario. As highlighted, the current status quo is facing increasingly strong tensions. These tensions are the result of incompatible and clashing sociopolitical factors paired with divergent preferences. In its current situation, the status quo is not robustly viable, and its existence will contribute to increasing the tensions between China and Taiwan. If the continuation of the status quo is the more likely scenario in the coming years, what can be done to mitigate the risk of conflict?

To avoid a conflict, the status quo must be reinforced. China’s strategy of deterring Taiwan’s formal independence is currently successful, thus removing a major cause for an outbreak of armed conflict (Schreer 2017). In addition, Taiwan understands that the United States does not support its independence (Haass and Sacks 2020). Therefore, Beijing’s growing doubts concerning the success of a long-term strategy has become the central factor which could lead to an escalation to military confrontation (Schreer 2017; Haass and Sacks 2020). In this context, the United States will play an essential role. Washington could potentially end its strategic ambiguity (Haass and Sacks 2020) and give a credible commitment to Taiwan (Blackwill and Zelikow 2021). From our perspective, the U.S. could adopt a position of dual clarity, making it clear that it would react to any Chinese use of force against Taiwan while reiterating its opposition to unilateral Taiwanese independence.

Strategic ambiguity is, indeed, contributing to making Taiwanese less supportive of de jure independence, but this would also be the case with dual clarity (Wang et al. 2024). Taiwanese are willing to trade their support for a unilateral de jure declaration of independence if it would imply that the United States would commit to defending the island (Wang et al. 2024). Strategic ambiguity resolves over a power distribution which is nowadays outdated, and Washington is becoming less capable of effectively deterring Beijing. Leaning toward dual clarity does not mean that the U.S. would renounce dual deterrence. On the contrary, we argue that it would increase the deterrent power of the United States. Taiwan would understand that its defense depends on its pledge to not unilaterally declare de jure independence. To avoid moral hazard, Washington could include clauses to avoid being drawn into an unwanted conflict with Beijing. On the other side of the Strait, dual clarity could produce positive outcomes by eliminating Beijing’s worst enemy concerning reunification—time. Indeed, as discussed previously, time is not playing in favor of the CCP, which sees the spread of Taiwanese identity as one of the biggest menaces to its unification plan. Dual clarity would not stop the growth of Taiwanese identity but could at least ensure that it does not translate into a unilateral declaration of independence. Moreover, a strong military commitment from the United States to Taiwan could favor the ties between Taipei and other Washington allies in the region and further abroad, thus increasing the cost for China in an invasion scenario. Finally, dual clarity would also raise the cost for the PRC to launch an invasion because China could not stress that they were reacting to an independence move by Taipei.

Of course, such an important change in the longstanding One China policy would result in increased tensions in the Strait. Indeed, China’s goal of reunification would not only face a reluctant Taiwan but a militarily committed United States as well. Such a policy should be coordinated with Washington’s allies, such as Japan and South Korea (B. Lin 2021; Sacks 2022), to ensure the efficacy of this new policy while also reassuring U.S. allies concerning the U.S.'s commitment to the region (Sacks 2022). This new paradigm in Strait crisis management should result in efforts to improve Taiwan’s international position, both concerning the island’s interactions with other governments and Taipei’s place in international organizations (C.-C. Chang and Yang 2020; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021; B. Lin 2021), to promote Taiwanese democracy (Haass and Sacks 2020; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021; B. Lin 2021) and to increase economic relations between the U.S. and Taiwan and between the island and Washington’s allies (C.-C. Chang and Yang 2020; B. Lin 2021), but also to expand Taiwanese military capabilities (B. Lin 2021; Sacks 2022).

However, this change has yet to come. Although President Biden affirmed several times that the United States would militarily intervene if facing an invasion of the ROC by the PRC, he mostly followed the usual strategic ambiguity in the Strait, notably by not specifically stating how and to what extent Washington would be militarily involved in the status quo (D. P. Chen 2022). Moreover, the president also reiterated that the U.S. does not support Taiwan’s independence. However, what can be seen is that strategic ambiguity is being adjusted based on increasing Chinese power, further reinforcing the Taiwan-U.S. relationship (Grzegorzewski 2022). Taipei is becoming more important in the balance of power in the region (Y. Lee, Shirouzu, and Lague 2021; Bellocchi 2023; Sacks 2023), and this is therefore reflected in more explicit support from Washington toward Taiwan (D. P. Chen 2022). Notably, the Biden administration has passed one of the most meaningful pieces of legislation since the TRA, the Taiwan Policy Act (TPA).[20] The TPA aims to enhance Taiwan’s defense capabilities by providing $4.5 billion over four years, to promote Taipei inclusion and participation in international organizations and to deter the PRC’s coercion against the island.[21]

As Taiwan is growing in importance, it seems very unlikely that this stance will be challenged by President-elected Donald Trump. Indeed, President-elected Trump aimed during his first mandate to contain the PRC’s increasing power while promoting Taiwan’s defense capability and international inclusion, notably through the TAIPEI Act and arms sales (Grzegorzewski 2022). In his recent presidential campaign, he endorsed a tough stand on China and threatened that he would impose additional tariffs on the PRC if the latter would invade Taiwan.[22] Nonetheless, it remains important to note that the newly elected President recently stated that Taiwan should pay, as it would do with an insurance company, for Washington’s defense and accused the island to steal the chip industry from the United States[23]. Nevertheless, Taiwan remains widely supported by both the U.S. Congress (Stampfl 2023) and American citizens (Kafura 2024). Given the increasing competition between Washington and Beijing, a profound change in the current One China policy seems improbable.

An overwhelming change in policy would increase the risk of intensification of tensions between Washington and Beijing. Therefore, the U.S. should reiterate that it would respect the “One China” policy and that it would not challenge any agreement between China and Taiwan on the condition that it has been achieved peacefully and with the consent of the people (Haass and Sacks 2020). In addition, China and the United States should mitigate their competition by addressing how to avoid systematic rivalry, creating crisis management mechanisms and regulating their competition concerning Taiwan (Blackwill and Zelikow 2021). The preservation of the status quo can only be achieved through significant diplomatic actions and profound mediation between China and the United States.

Concerning Taiwan, its biggest vulnerability, with regard to which China’s coercive actions can be more effective, concerns the public’s low confidence about the future (R. Bush 2019). The growing economic dependence on China, the increasing international isolation, the PLA’s threat and the uncertainty concerning U.S. commitment are factors that undermine the prospect of a good future for most Taiwanese (R. C. Bush 2017). The political polarization in Taiwan makes China’s intimidating and coercive policies more sensible (R. C. Bush 2017). The island would benefit from a greater implication in the international community resulting from a change in strategic ambiguity, which would allow it to better face Chinese pressure.

Whether through the continuation of the status quo, unification or separation, one side of the Strait will be profoundly dissatisfied with the outcome. The way the status quo has evolved does not really allow us to have a positive stance concerning further peaceful advancements. Rather, the situation is clearly becoming more and more dangerous. Each side will have to carefully act because the margin of error is very thin. In conclusion, there is not a simple and rapid solution to this issue, and the tensions in the Strait will probably continue to grow. The status quo is today more than ever in a deadlock, and whatever its evolution will be, it will be harmful for a potential peaceful resolution. With this conclusion in mind, all parties involved need to do everything possible to avoid the outbreak of war.

The term “reunification” is used when referring to Beijing’s point of view concerning the subject and “unification” from an external point of view.

For the Shanghai Communiqué, Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, United States Department of State, “Joint Statement Following Discussions With Leaders of the People’s Republic of China,” see: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v17/d203 and the Normalization Communiqué, American Institute in Taiwan, “U.S.-PRC Joint Communique (1979),” see: https://www.ait.org.tw/u-s-prc-joint-communique-1979/

American Institute in Taiwan, “Taiwan Relations Act,” see: https://www.ait.org.tw/policy-history/taiwan-relations-act/

American Institute in Taiwan, “Declassified Cables: Taiwan Arms Sales & Six Assurances (1982),” see: https://www.ait.org.tw/declassified-cables-taiwan-arms-sales-six-assurances-1982/

U.S. Secretary of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021,” see: https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF

D. Tang 2024, “Taiwan is selling more to the US than China in major shift away from Beijing,” see: https://apnews.com/article/china-taiwan-us-exports-investment-308c4efe8e54bef3b65f68db565437f3

SIPRI, “SIPRI Military Expenditure Database,” see: https://milex.sipri.org/sipri

Office of the President, Republic of China (Taiwan), “Inaugural address of ROC 14th-term President Tsai Ing-wen,” see: https://english.president.gov.tw/News/4893

Taiwan People’s Party, “Cross-Strait Relations,” see: https://www.tpp.org.tw/en/our_platform-detail.php?id=24

Ibid.

Central Election Commission, “2000 Presidential and Vice Presidential Election,” see: https://web.cec.gov.tw/english/cms/pe/24831

Ibid.

Election Study Center, “Taiwanese / Chinese Identity (1992/06~2024/06),” see: https://esc.nccu.edu.tw/PageDoc/Detail?fid=7800&id=6961

Ibid.

Election Study Center, “Party Preferences (1992/06~2024/06),” see: https://esc.nccu.edu.tw/PageDoc/Detail?fid=7802&id=6964

Election Study Center, “Taiwan Independence vs. Unification with the Mainland (1994/12~2024/06),” see: https://esc.nccu.edu.tw/PageDoc/Detail?fid=7801&id=6963

Ibid.

Republic of China (Taiwan) Government, see: https://www.taiwan.gov.tw/content_7.php

Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China 2005, “Anti-Secession Law,” see: http://eng.mod.gov.cn/xb/Publications/LR/4888396.html

Taiwan Policy Act, see: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/4428/text/is

Ibid.

Mistreanu 2024, “China is bracing for fresh tensions with Trump over trade, tech and Taiwan,” see: https://apnews.com/article/trump-china-tariffs-taiwan-foreign-policy-7351ce1069654f1c1aefb560b36dcc17

Ibid.