Introduction

The geopolitical situation surrounding Taiwan’s status represents one of the main challenges for world peace. The status quo, which represents a permanent separation from the mainland, amounts to a situation of neither peace nor war, but it is also portrayed as a deadlock (Goldstein 2002). The status quo not only represents dyadic and regional concerns but also symbolizes the competition between Washington and Beijing in the race to be the first world power (Kong 2015; Yu 2017; Xiying 2021; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021). The Taiwan Strait is characterized by a precarious peace and is facing a very conflictual period bringing its functionality and continuation into question (Blackwill and Zelikow 2021). Taiwan’s inestimable military, economic, and political value (Sacks 2023) possess profound implications for the understanding of the distribution of power in the Asia-Pacific region and represent a major stake for the stability of the international order.

By proceeding to a comparative political analysis, this research aims to answer the following research question: Which factors make the status quo between Taiwan and China a central issue for the international order?

Literature review

The relations between Beijing and Taipei have been largely analyzed through various lenses: China’s coercive attitude towards Taiwan (S. Lee 2015; Schreer 2017; Lai 2017; R. Bush 2019; Krumbein 2020), economic relations (Chiang and Gerbier 2013; C.-C. Chang and Yang 2020), the “One China” principle (Kan 2001; Huang 2017), and identity (Hughes 2011; Zhong 2016; Zhu 2017). This research aims to provide a different approach to the study of Taiwan’s situation by placing it as a central factor in the power competition between China and the United States. This design is intended to enrich our understanding concerning two central particularities of Taiwan that have not been sufficiently considered for the future development and implications of the subject.

Firstly, it possesses deep ramifications for understanding the balance of power in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond. Taiwan is not only a small island deprived of the status of state but also is a vibrant democracy with deep economic and political interactions with the international community and represents a central variable in the comprehension of how the international order may evolve. The literature too often solely describes Taiwan as a strategic objective for China and the United States but rarely as a dynamic actor that can have an influence over the power competition between the two dominant nations. Taiwan is, indeed, a strategic objective. However, limiting it to the role of passive stakeholder is reductive. By placing the ROC in the equation of the power distribution, we aim to further highlight how crucial the island is for the international order.

Secondly, the legal vagueness surrounding Taiwan’s status is an understudied variable in the comprehension of the uncertainty in the Strait. By emphasizing the role played by international law in the maintenance and shaping of status quos, we aim to highlight the relevance of considering legal factors in the comprehension of the current Taiwanese situation. Indeed, the extremely tense context in the Strait and potential solutions to the threat of a Chinese invasion have mostly been oriented towards enhancing Taiwan’s military capabilities (Tan 2014; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021; Sacks 2022). By addressing how international law is weakening Taiwan, we want to draw attention to the fact that ensuring proper access to it would be a way to improve Taipei’s resilience in the face of Beijing’s increasing military deterrence and political coercion.

Consequently, we will base our analysis on the power transition theory and international law as factors. These two frameworks have been chosen for two reasons. Firstly, both have been highly influential in how the situation surrounding Taiwan has evolved since 1949. To be able to study the status quo, is it therefore valuable to use both as bases of study. Secondly, analyzing the linkage between two antipodal frameworks enhances our understanding of how they interact. International law, which embodies cooperation and shared values and norms, is supposed to mitigate competition between states. However, as we will develop, the strategic considerations of the power transition theory are reflected in the international legal order. Combining the two perspectives offers a complete theorical framework for further exploration of Taiwan’s situation.

The status quo and the power transition theory

In the power transition theory, the world is hierarchically organized and divided, with the highest position being occupied by the dominant nation and the lower ones by colonies, which have today totally disappeared (Organski 1968). In between these two categories are arranged, from the higher to the lower, the “great powers,” the “middle powers,” and finally the “small powers” (Kugler and Organski 1989). The dominant nation creates and sustains an international order in which most great powers are satisfied (Kugler and Organski 1989). However, some of these great powers, which cannot compete with the dominant nation at a given point in time but possess the potential to do so in the future, are dissatisfied with the international order and are potential challengers to the established status quo (Kugler and Organski 1989).

The power transition theory states that international competition is not driven by the willingness of a country to maximize its power, but rather by the potential net gains that could be achieved from conflict or competition (Organski 1958). A conflict could consequently occur when a state concluded that its net gains would be higher in case of conflict, compared to peaceful competition (Organski 1958). However, power is a determinant factor concerning how the international order works. The number of countries which are dissatisfied with the status quo may be large, but if their power is weak, they do not represent any threat or competition to the dominant nation (Kugler and Organski 1989). Nevertheless, a great power nation which is displeased by the current status quo may upset it.

Therefore, the status quo requires, to be stable, that a massive power preponderance supports it (Kugler and Organski 1989). Instability is likely to occur when a challenger has reached parity with or has surpassed the dominant nation (Lemke 2004), which increases the probability of conflict (Kugler and Organski 1989; Rauch 2018). The closure of the power gap by the challenger nation makes it increasingly unwilling to accept its subordinate position and an established status quo not in line with its objectives (Kugler and Organski 1989). An entry into war will therefore depend on the will to initiate a war, which is motivated by dissatisfaction with the current status quo, and on the opportunity to begin it, which will depend on the distribution of power (Lemke and Werner 1996).

Although the power transition theory sheds light on how conflicts begin, it possesses two limitations: Firstly, it considers the point in dispute, which is the status quo, only at the global level (Lemke and Werner 1996). Secondly, the theory suggests that relations are peaceful until dissatisfaction reaches a tipping point. In response, Lemke and Werner (1996) instead used the term “commitment to change” as the critical level that will initiate a conflict because they claimed that “the challenger’s willingness to go to war is not determined by the absolute level of dissatisfaction, but rather by a relative assessment of the challenger’s desire for change and the dominant country’s desire for stability” (Lemke and Werner 1996, 240).

Additionally, Lemke and Werner (1996) and Lemke (2004) extended this theory to the regional level. Each system possesses its own status quo and a set of states that can influence the latter (Lemke and Werner 1996). As stated by Yilmaz and Xiangyu (2019), at a regional level, dissatisfaction may lead to conflict between the regional dominant nation and the dissatisfied countries within a local framework. This also applies to power transitions within a dyad (Sobek and Wells 2013). Indeed, when a power transition occurs between a pair of nations, the risk of militarized conflicts increases (Sobek and Wells 2013). The likelihood of war occurring also grows in the context of a dyad that includes a contiguous nation or a great power (Weede 1976), and dissimilar preferences for the international status quo also strongly increase the likelihood of dyadic conflict (Benson 2007).

A regional status quo must operate within the context of the international one, which may result in limitations on the range of actions available to the parties involved in the local status quo (Lemke and Werner 1996). A country hierarchically higher might interfere and prevent regional conflict, either by deterring or reassuring the dissatisfied challenger. Hence, the more important a local status quo is for great powers, the more the autonomy of the parties will be restricted (Lemke and Werner 1996). Consequently, a challenger nation may want to shape the international system to have a larger range of actions available to it in a regional status quo in which it is involved. As elaborated by Kugler and Zagare (1987, 1990), in the power-overtaking structure, the further a challenger nation increases its power, the more it will be able to resist the deterrence of the dominant nation and gradually begin to engage in mutual deterrence with the latter, which may end in a reversal of deterrence in favor of the challenger.

The power transition theory can be further extended to international law. Although the latter embodies values, such as cooperation, negotiations, and the establishment of shared values and norms, which should mitigate the rivalry between states, we argue that power competition exceeds the primary goal of international law and is consequently reflected in the way the latter is used. International law represents a realm in which great powers can exercise their dominance to pursue their political goals. When analyzing the power structure between the United States, Taiwan, and China, highlighting how power is mirrored in the international legal order emphasizes that variations in the balance of power impact the interpretations and applications of international law regarding Taiwan’s status.

International law

The interrelationship between power and international law

International law refers to the set of legal rules, norms, and standards that govern relations between sovereign states and other entities recognized as international actors. International law is assumed to depend on a balance of power, to refuse the formal recognition of a hierarchical structure, and to aim to limit the power of the dominant states (Krisch 2005). On the other hand, the dominant nations are considered to be averse to following the rules of international law because doing so would imply a renunciation of a part of their power (Krisch 2005). However, international law follows the same structure as the one presented in the power transition theory. The international order is hierarchically organized, with, at the top, a dominant nation that maintains the order based on its viewpoint (Burke-White 2015). The latter is contested by dissatisfied great powers that aim to challenge and shape views according to their national interests (Burke-White 2015). We earlier discussed how the power-overtaking structure influences the international order (Kugler and Zagare 1987). In international law, the same logic is at work. In a situation involving power shifting, the ascendent state will be less inclined to make tradeoffs while the descendent one will have to make concessions (Meyer 2010). Additionally, power also influences who is likely to be sanctioned for not respecting the international rules (Yasuaki 2003). Progressively, the dissatisfied state will become more resilient to the sanctions imposed for not complying with international law and will be able to convert its power into legal influence (Burke-White 2015).

Consequently, international law is influenced by how power is distributed among the parties involved (Steinberg and Zasloff 2006). For a long time, international law has been aligned with Washington’s standpoint (Koskenniemi 2004). The dissatisfied great powers, and notably China, aim to challenge the position of the United States concerning its domination of the international legal order, particularly regarding the concept of sovereignty, with the desire to shape it in accordance with their preferences (Burke-White 2015). The existing legal order is therefore highly sensible to power shifting in the international order (Burke-White 2015). Being a dominant nation offers the possibility of being above the law and using the latter to exercise its dominance (Krisch 2005).

Our theoretical framework sheds light on how the power distribution and international law are closely related and interact together to shape the international order. We choose to analyze the situation of the status quo through the lenses of the power transition theory and international law because they offer crucial information concerning how a status quo will evolve and for what reasons.

To understand why the status quo between Taiwan and China is a central issue for the international order, we will compare it to other status quos to highlight how it differs. Using case studies for our analysis allows us to achieve three objectives. Firstly, to test how international law and power shape different status quos. Secondly, and based on the first point, to highlight specific similarities and differences that enrich our understanding of Taiwan’s status quo. Thirdly, to provide insights into why Taiwan’s situation is of particular concern for the international order.

Taiwan’s situation compared to other status quos

Case studies selection

Our case studies are centered around three territorial disputes that resulted in the establishment of an ongoing status quo. Based on the framework they offer, the separation of Korea into two nations, the conflict between Pakistan and India centered on the Kashmir region, and the dispute involving Greece and Turkey in Cyprus are the cases selected. They have been chosen because they are characterized by a particular international law framework and illustrate how the involvement of great powers has an influence over the dynamics of a status quo. These cases echo our theoretical framework and offer variations concerning how it applies to real cases. By integrating the theoretical perspectives previously developed, we will demonstrate how status quos can evolve and be maintained under international law and the power transition theory. This will be further used to highlight how Taiwan’s situation differs from other status quos.

The two Koreas

Korea’s status quo has been constructed within a larger, international status quo which opposed two blocs (Weede 1976), in conjunction with the Chinese intervention (Tammen, Kugler, and Lemke 2012), and the separation of the country into two distinct parties was not a choice made by Koreans. Indeed, towards the end of World War II, the United States and Soviet Union agreed to temporarily divide Korea into two parts with the 38th parallel as the dividing line[1]. However, it soon emerged that neither of the two great powers would accept losing its ally in favor of unification, and a war therefore exploded in 1950 when the North attacked the South in June of that year and almost conquered the entire peninsula[2]. The war eventually ended in 1953, and the status quo took form around the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), which has since that time concentered the strong tensions between the two nations (O’Neil 2003).

The Koreas’ status quo has another specificity which lies in the fact that both South and North have sought reunification, but on their own terms. Indeed, this mutual agreement concerning reunification as a shared goal is often a particular situation for a status quo marked by unsatisfied parties who are forced to accept an unwanted compromise (Goldstein 2002). The gradual abandonment of North Korea’s “One Korea” policy, coupled with several Joint Declarations[3], were considered important and shared steps towards a peaceful resolution of the status quo despite the continuous tensions. This mutual objective denotes with others territorial divisions that have taken place in history, where giving up one’s share of territory to change the status quo was mostly impossible because of the constructed “indivisible” character given to the notion of territory (Goddard 2009). This situation highlights the important role assumed by international law to reduce competition between countries and establish shared objectives.

Another important characteristic of this status quo comes from its instrumentalization in the international status quo. Indeed, nowadays, the two dominant nations, China and the United States, are concerned due to the importance of Korea to the security and stability of the East Asia region (Han 2011). This status quo has taken the form of quadrilateral relations in which both Beijing and Washington are seeking to pursue their regional objectives to assert their position in the international system (Revere 2015). Consequently, the peace process between the two Koreas is a ground on which the two nations clash over the domination of the international status quo (Güneylioğlu 2017).

In this context, the end of the status quo in favor of unification may be unattractive for China as it would imply an economically and militarily stronger Korea on its border, especially if Korea remains a Washington ally and host to U.S. troops (Revere 2015). For the United States, a unification followed by a consequent denuclearization of the North (Revere 2015) would be a suitable situation resulting in the disappearance of a country which, although not powerful enough, is a challenger to the international status quo.

The status quo between the two Koreas is the perfect illustration of how a regional status quo possesses deep implications for the balance of power between two dominant nations.

Kashmir region

In 1947, when the British ruled over India, the Kashmiri ruler agreed that his kingdom would join India under the condition that Kashmir would preserve its political and economic sovereignty while its defense and external affairs would be dealt with by India (Bulbul 2021). However, the newly created Pakistan, predominantly Muslim, fomented to force the accession of Kashmir to Pakistan (Nawaz and Guruswamy 2014), based on their belief that Kashmir, which is a majority Muslim state, rightfully belonged to them[4]. This resulted in 1947 in the first of three major wars over Kashmir[5], which ended with the creation of a ceasefire line by the United Nations that divided Kashmir into Indian and Pakistani territory (Bulbul 2021). Despite this, two more wars exploded, in 1965 and again in 1999, in addition to various other clashes across the border[6].

The first particularity is that the status quo has not been able to stop the open conflicts. In addition, this status quo concerns a former third-party state, which is the central object of the conflict. Mutual dissatisfaction with the current status quo drives the two countries to take unilateral actions to try to change the territorial status quo (Nawaz and Guruswamy 2014).

Additionally, contrary to the situation in Korea, the major powers have not been immediately involved in the status quo (Thapliyal 1998) and have had little interest in this conflict (Joshi 2020), avoiding entering directly into the clash until 1971 (Thapliyal 1998). However, China involved itself sooner because of disputes concerning its Himalayan border with India. In 1962, China attacked India in the Sino-Indian war, which ended in Beijing’s favor (Bokhari 2020). Pakistan, which was seeking to internationalize the issue, used this Sino-Indian conflict in its favor, and in 1963 Islamabad and Beijing signed the Sino-Pakistan Agreement, which resulted in Pakistan’s giving up a territory it disputed with India to the PRC, which further drew China into the Kashmir conflict (Joshi 2020; Bokhari 2020). This move by Pakistan turned the bilateral status quo into a trilateral one (Joshi 2020). China’s progressive implication in the Kashmir question resulted in Washington’s being motivated to act[7], and now both nations are pushing to maintain the status quo to pursue their regional objectives, thus exacerbating regional tensions and creating an impasse with regard to the Kashmir conflict’s resolution (Imran and Ali 2020). Although the fact that both China and the United States are involved in a regional status quo is not surprising, as they are involved in an international one in which the two nations are fighting for control, the mutual objective to preserve the status quo denotes with the generalized opposition between the two countries on almost every issue (Xiying 2021).

In addition, international law also has failed to resolve this territorial dispute. India and Pakistan do not agree on whether international law applies in Kashmir. While Pakistan looks at the Kashmir status quo as an international dispute, India considers it to be a bilateral issue and an internal matter (Joshi 2020; Bulbul 2021). India seeks to limit the purview of international law (Bulbul 2021), and its recent unilateral choice to abrogate Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which granted Kashmir a quasi-autonomy, resonated as an attempt to reinforce India’s stance concerning this status quo (Joshi 2020). This echoes with the fact that being a great power offers the possibility of using international law to pursue domestic goals.

Cyprus

Britain ruled over the island until 1960, when it created, with Greece and Turkey, the independent Republic of Cyprus (Aksu 2003). Cyprus was composed of a majority of Greek communities and a minority, roughly 20%, of Turkish ones. The constitution stipulated power-sharing between them and granted to the Turkish minority veto powers and representation in the national services (Aksu 2003). In 1963, the President of Cyprus introduced a thirteen-point amendment to the constitution that aimed to guarantee decision-making by the Greek Cypriot majority, and which was rejected by the Turkish society (Direkli 2016; Aksu 2003). This situation soon devolved into an ethnic conflict, and the Turkish side eventually withdrew from the government (Direkli 2016; Aksu 2003). Following a coup d’état in 1974 by the Greek military junta, Turkey militarily intervened against it in Cyprus (Direkli 2016; Chan 2016). During the subsequent peace talks, Turkey conducted a second military operation and captured 36% of Cyprus (Direkli 2016; Chan 2016), proclaiming it since 1983 as the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus,” administered by Turkish Cypriots with Turkey’s support[8]. This last Turkish military intervention established the current status quo.

The first particularity is that although the U.S. and the USSR were once again involved in this conflict, their implication was weaker compared to that in other disputes. Indeed, the Cyprus conflict took place within the U.S. sphere of influence rather than in a relatively neutral zone, therefore limiting the USSR’s potential range of actions (Aksu 2003). The notion of “sphere of influence” introduces an interesting point for the power transition theory and adds a layer of complexity to it. It extends the conception of regional status quo by presenting how soft power, by promoting economic, political, or cultural cooperation, can increase a state’s influence in a region. For a nation, extending its sphere of influence results in more control over a region and can mitigate the influence that other great powers have (Niebel 2020). Consequently, for a dissatisfied state, expanding its sphere of influence may lead to increasing its power in a regional status quo, eventually resulting in an enlarged power at the international level.

Additionally, the Cyprus case highlights how the notion of geographic location impacts the value of a status quo. Indeed, the island represented a strategic military stake, notably because of its location in the Eastern Mediterranean (Cid 2016; Yellice 2017; Koura 2021). If Cyprus had fallen into the USSR’s sphere of influence, the United States would have faced a Cuba-like situation in the Mediterranean (Adams 1972; Chan 2016; Yellice 2017).

The third specificity of this status quo is that it did not only emerge because of territorial disputes, but also because of identity divergences. Indeed, the residents on the island portrayed themselves as Greek or Turkish before they thought of themselves as Cypriots (Direkli 2016). The current status quo first erupted because of ethnic conflict and only took a territorial dimension after the separation in 1974. The two sides have developed entirely separately since 1974, and even after the opening of the first checkpoints on the Green Line in 2003, they have continued to have limited contact (Flynn and King 2012). The Fifth Annan Plan, which was a UN proposal for reunification, was strongly refused by the Greek Cypriots while being largely accepted by the Turkish ones (Webster 2005). This is interesting because it demonstrates that parties in a status quo may pursue totally different goals.

Finally, this status quo illustrates how hard it is for international law to resolve a status quo. Following the Turkish military intervention in 1974, the General Assembly passed Resolution 3212, which “calls upon all states to respect the sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity and non-alignment of the Republic of Cyprus”[9], and with which Turkey has not complied (Lulic and Muhvic 2009). The unilateral declaration of independence of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in 1983, based on the right to self-determination, has been rejected by the Republic of Cyprus, the United Nations, and the international community (Lulic and Muhvic 2009). Therefore, since 1983, the island has been divided into two autonomous administrations, one of which is de facto independent while the other one is de jure. International law has been strongly opposed to Turkey’s invasion but has not managed to resolve the Cyprus problem (Lulic and Muhvic 2009).

The specificities of Taiwan’s status quo

Although we carefully selected our case studies, it is important to mention that there are some limitations in the comparisons. Firstly, we stressed the importance that the notion of region possesses in the power transition theory. Note that Cyprus is not part of the same region as Taiwan. Regions are sums of values, power distributions, and sociopolitical variables that may differ from one to another. Hence, potential biases may exist when inferring our findings to the Asia-Pacific region. Secondly, we earlier highlighted that the more important a local status quo is for great powers, the more the autonomy of the parties will be restricted. Precisely evaluating the importance of a status quo is difficult. Nonetheless, it remains necessary to acknowledge that, concerning the study of Taiwan’s situation, the factors we discussed may materialize themselves differently because of how deeply the dominant nations are involved in it. However, this could also be perceived as a particularity of Taiwan.

Nevertheless, these different status quos have offered us important information that enriches our understanding of Taiwan’s situation. Most notably, they underline how power and legal factors are central to the evolution of status quos. They emphasize the significant role of the dominant nations in shaping the status quos, the struggle of international law in resolving these disputes, and how other variables, such as the number of states involved or the reason for the separation, contribute to the complexity of the situation.

The case studies highlighted several factors that set Taiwan’s situation apart from other territorial disputes and elevate it as a particular concern for the international order. Firstly, Taiwan represents a direct dispute between Washington and Beijing and a major stake in the power competition between the two dominant nations. Consequently, contrasting with our case studies, Taiwan’s situation is highly relevant for the structure of the international order. Moreover, the status quo between Taiwan and China does not possess a factor that can mitigate the tensions. Whereas the two Koreas have a common goal of reunification, both Washington and Beijing pursue the goal of preventing the outbreak of war in the Kashmir region (I. J. Chang 2017), and the Cyprus status quo does not represent a major stake for the international order, Taiwan’s situation differs totally. Not only is there no mutual agreement for a peaceful unification (Schreer 2017; Blackwill and Zelikow 2021; Mastro 2021), but the more time passes, the more the political separation in the Strait widens (Rigger et al. 2022). Indeed, the Taiwan status quo does not represent an ethnic nor a legal division but, mainly, a political one (Zhong 2016; Lin 2021). Finally, Taiwan’s situation embodies particularities concerning its legal aspect. Taiwan is neither considered a de jure state, as the two Koreas are, nor politically administered by China, as the Kashmir region is by India, nor banned from the international community as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is. The island inhabits an ambiguous spot, by being an important actor in the international system while not being allowed to join international organizations. This application of international law regarding Taiwan’s status increases the uncertainty in the Strait.

These differences provide enriching insights concerning the uniqueness of the ROC. The main differences that arise are the role and relevance embodied by Taiwan in the regional and international balance of power and how international law contributes to the instability of the situation. Analyzing these factors from the perspective of the framework of our research, namely the power transition theory and international law, further enhances our understanding concerning why Taiwan’s situation is a central issue for the international order.

Taiwan’s relevance for the international order

As we highlighted earlier, Taiwan cannot be considered solely as a territory that is disputed between the two leading powers. Understanding Taiwan through the power transition theory underlines how the island is critical for stability in the region and beyond. Taipei represents military, legal, economic, and democratic interests (Sacks 2023). In the balance of power, Taiwan weighs heavily. Keeping Taiwan as an ally, or assimilating it, is a major stake for Washington versus Beijing, respectively. None of the other ongoing status quos symbolizes such a significant situation for the international community. Even when considering the similarities between Taiwan’s situation and our case studies, the result is that the implications and stakes are beyond what other status quos represent.

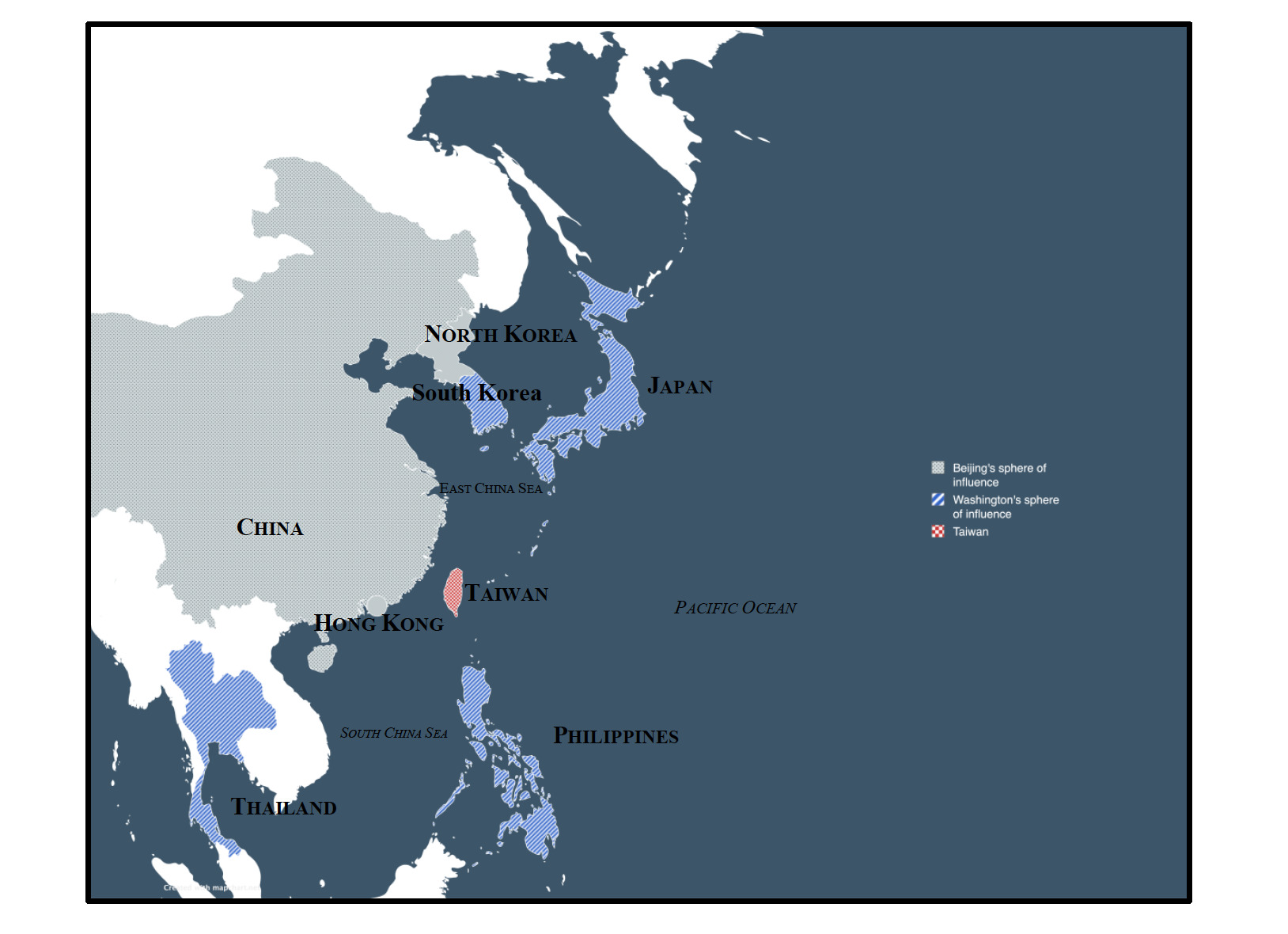

Firstly, Taiwan’s geographic location is highly strategic. The island is positioned between China and two allies of Washington, Japan and the Philippines. Moreover, in conjunction with Thailand and the Philippines, Taipei is restricting China’s access to the South China Sea, and to the Pacific Ocean.

The map illustrates one of the main reasons Taiwan is a central variable in the power distribution between China and the United States. By absorbing the island, the PRC would be able to break the encirclement by Washington’s allies and extend its military power and deterrence in the region, eventually diminishing the influence of the U.S. (Bellocchi 2023; Sacks 2023). On the contrary, if Taiwan totally broke from China’s control, the result would be an enlarged distribution of power in favor of the United States and a reduced range of action for the mainland (Sacks 2023).

Secondly, the ROC is positioned along central shipping routes (Bellocchi 2023) and is a key actor in global technology supply chains, especially those for semiconductors (Sacks and Hillman 2021), making Taiwan an indispensable partner for almost every advanced civilian and military technology (Y. Lee, Shirouzu, and Lague 2021). Controlling the island would offer domination over roughly 70% of the world’s semiconductors (Sacks 2023). Consequently, Taiwan has a pivotal role in the balance of power in the region, and it is not surprising that the two dominant nations clash to make it fall under their sole influence.

Indeed, this situation is, in part, fueled by the fact that Taiwan fails to totally fall into the sphere of influence of either the United States or China. Although the Asia-Pacific Region is historically under the sphere of influence of the U.S., and Taipei and Washington have close ties, China seeks to expand its influence in the region, notably in the South China Sea, and despite the tensions, still retains strong leverage over Taiwan (Schreer 2017; C.-C. Chang and Yang 2020). This situation creates an even more complicated framework in which the two dominant nations regularly test each other. This not only brings more uncertainty to the region but also increases the risk of escalation at each confrontation. This uncertainty is a particularity of Taiwan’s situation. Compared to other status quos, that now seem to be an established fact, Taiwan’s situation is continuously evolving. Analyzing it under the framework of the power transition theory highlights how relevant Taiwan’s situation is for the international order and sheds light on how the latter may be shaped in the future by the island’s evolution.

International law, legal vagueness, and power

Finally, legal vagueness makes of Taiwan a particular situation in which it is possible to study how power and international law interact. The change in the recognition of the legitimate government of China has been a major transformation in the evolution of the status quo and had deeper implications for the international community (Winkler 2012; R. C. Bush 2017). Nowadays, the failure of international law to settle the status of Taiwan grants China the ability to stress its position and to assert its strategic objectives on the matter. By increasing its power, China has been able to emphasize that the Taiwan issue represents a national concern and to stress the acceptance of the “One China” principle as mandatory in order to engage in diplomatic ties with Beijing. The CCP uses international law as a strategic tool to achieve unification, portraying the “One China” principle as a widely accepted norm. China considers Taiwan to be part of its borders and stresses that international law can only be applied between states, thus excluding the status quo from being considered by the international community (Fang 2023). China’s ability to gain general acceptance of the “One China” principle has had the effect of strongly erasing Taiwan from the international scene (Van Fossen 2007).

China has limited Taiwan’s international implication by blocking its participation in international organizations (Chen and Zheng 2021) and by coercing the loss of its precious political allies (Breuer 2017; Tuman and Shirali 2017; Mastro 2021). The exclusion of the island from the international sphere supports the long-term vision that the Chinese leaders have concerning reunification. The PRC has strongly focused on isolating Taiwan from the United States (Goldstein 2002; Huang 2017). China has tried to cut any involvement by Washington in cross-straits relations to increase Chinese leverage over Taiwan (Huang 2017). From Beijing’s point of view, the more Taiwan is isolated, the more it will be weakened and closer to reunification (Rigger 2011), and any international recognition reached by Taiwan is a step in the direction of formal independence (Saunders 2005).

Indeed, being recognized internationally is vital for Taiwan because it would prevent China from absorbing it for fear of a reaction from the international community (Rich 2009) and would grant the ROC a kind of deterrent power to use over the PRC (Huang 2017). As pointed out by Van Fossen (2007), the diplomatic system’s disconnection from which Taipei suffers is limiting Taiwan’s ability to express itself internationally while restraining its international exposure.

In the realm of international law, the power transition that has occurred has played in favor of China, which has been able to advance its position over Taiwan and the United States. Nowadays, the most notable legal commitment from the United States towards the ROC is the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act (TRA) (Turin 2010), which grants Taiwan defensive weapons based on Washington’s judgment of Taipei’s needs and which created an “unofficial embassy,” thus maintaining de facto diplomatic relations between both parties (Turin 2010). Moreover, recent, and mostly symbolic, laws have passed with the aim of asserting Taiwan’s international inclusion. Remarkably, the 2020 TAIPEI Act aims to ease Taiwan’s gaining entry to international organizations, notably by encouraging other countries to reinforce their bonds with the ROC (Stampfl 2023).

In conclusion, the power transition that took place between Beijing and Washington has repercussions for how international law is handled. A less deterrent United States and a more confident China has led to the current situation. Power and law are intrinsically linked, and Taiwan’s situation illustrates that perfectly.

Conclusion

This research aimed to illustrate the reasons Taiwan’s situation represents a fundamental matter for the international order. The objective was to approach the island not only as a major stake for dominant nations but also as a central actor in the stability of the region and beyond. Comparing Taiwan to other status quos underlines how deeply the island is implicated in the power calculation. Of course, every country and every territorial dispute is a piece of the global puzzle. However, when considering Taiwan, the implications are bigger. The way Taiwan fits into the power transition that is occurring between China and the United States highlights how this situation is crucial for the international order.

In the power balance, Taiwan’s geographic location and its military, economic, and technological value can redistribute power both at the regional and international levels. We previously discussed the power-overtaking structure (Kugler and Zagare 1987, 1990). The structure is composed of five stages. In our research, stage 1 corresponds to the power preponderance in favor of the U.S., and stage 5 would be reached if one day China achieves the reversal of the situation by becoming the sole dominant nation. Currently, we are at stage 3, with mutual deterrence and a relative power distribution between the two parties. In this context, understanding Taiwan through the power transition theory sheds light on how and why it represents a particular situation for the international order. The way in which Taiwan’s situation will evolve will play a crucial role in how the Asia-Pacific region will be shaped in the coming years.

Further research may analyze how Taiwan’s situation is becoming increasingly relevant for its neighbors. Notably, Taiwan represents a strategic interest for Japan (Bercaw 2024; Takei 2024). Our research shows how Taiwan represents a barrier containing the expansion of Beijing’s sphere of influence. In the battle for power dominance, the island is not only limiting the expansion of the Chinese sphere of influence but also reducing potential threats to Washington’s allies in the region. Greater support from the latter towards Taiwan could result in shaping the current distribution of power in the region and have a significant impact in the power competition between the two dominant nations. This could additionally highlight how entangled Taiwan is with the notion of power.

Moreover, extending the power transition theory to the realm of international law underlines how power must not only be understood in terms of military and economic factors but also in legal terms. Analyzing Taiwan’s situation under this framework shows how the power transition occurs equally in the legal sphere. Newly acquired Chinese power confers on the PRC the possibility of pursuing its objectives with regard to the ROC by influencing the international law. By adopting this method, we highlighted that one of the main weaknesses of Taipei and a factor undermining the stability of the region is the legal vagueness surrounding the island’s status. Further research may focus on how to reinforce the Taiwanese legal position, how that would contribute to enhance Taipei’s defense capabilities, and what possible outcomes may arise for the international order. Notably, a greater integration by Taiwan’s neighbors on diplomatic and economic questions could raise the cost of a conflict’s breaking out in the Strait, thus stabilizing the region. Our research underlines how important the legal factors are in shaping a status quo. Consequently, this framework should not be excluded from discussions concerning how to reinforce Taiwan in the face of growing threats in the Strait.

Nevertheless, our research has certain limits and would benefit from the addition of complementary elements. Firstly, it could be interesting to look at other status quos that have been peacefully resolved, as with the two Germanys, to identify their particularities and to discuss if these are transferable to Taiwan’s situation. Although the status quo between Taipei and Beijing has far too many points of divergence, and therefore finding a point of understanding and mediation turns out to be almost impossible, it could still be interesting to develop further this path. It could make it possible to understand how international law can achieve compromises between dominant nations, as happened between the USSR and the U.S., concerning matters that directly impact the balance of power and to identify if this could be replicated with the United States and China.

Secondly, the “One China” principle is fundamental for how China uses international law. It would have been interesting to further develop this subject to better understand the way it is used to pressure other countries to accept Beijing’s stance. The “One China” principle undoubtedly enforces the CCP’s position with the countries it engages. It favors, according to the power transition theory, China’s ability to challenge the established power distribution because it compels other nations to accept Beijing’s stance. Therefore, this central policy could have been analyzed to further highlight a major point in the power shifting between the U.S. and China, and a particularity of Taiwan’s situation.

However, despite these points that could have been deepened, we hope to have been able to contribute to knowledge about the importance of Taiwan in maintaining the international order by emphasizing its central role in the balance of power. The island may be a small territory but is above all a major player in international relations and deserves to be understood accordingly. Taiwan’s situation is a unique context in which it is possible to observe how the notion of power manifests itself and influences international relations.

Office of the Historian, see: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/korean-war

Ibid.

The South-North Joint Declaration, see: https://peacemaker.un.org/node/9208, the Declaration on the Advancement of South-North Korean Relations Peace and Prosperity, see: https://peacemaker.un.org/node/9001, and the Panmunjom Declaration, see: https://bit.ly/3rMgOi0

Office of the Historian, see: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/india-pakistan-war

Center for Preventive Action, Council on Foreign Relations, see: https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-between-india-and-pakistan

Ibid.

Office of the Historian, see: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/india-pakistan-war

Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, U.S. Department of State, “U.S. Relations With Cyprus,” see: https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-cyprus/

Resolution 3212, see: https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/un-documents/document/cyprus-3212-xxix.php