Introduction

On January 13, 2024, Taiwan elected Lai Ching-te of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) president in the country’s closest election since 2008. Lai, long a pro-independence supporter, would have been hard to predict as a viable presidential candidate a decade ago. Two broad factors aided in this victory. Lai, along with the DPP more broadly, moderated his stance to appeal to status quo supporters over the last decade, and Hou You-ih of the Kuomintang (KMT) and Ko Wen-je of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) were unable to coordinate on a unified campaign against Lai. Ultimately, Lai won with 40.05% of the vote to Hou’s 33.49% and Ko’s 26.46%.

This analysis asks whether the results of this election would have differed under preferential voting rules. Despite the likelihood of a winner for the first time since 2000 without a majority of the vote, little analysis directly attempted to measure preferences regarding the candidates in relation to one another. Runoff elections remain common in presidential systems, especially those with more than two parties, and Taiwan briefly considered such a system prior to the first direct presidential election in 1996. Meanwhile, preferential voting systems, such as the alternative vote used in Australia, have become increasingly popular globally. Initial coverage of the 2024 election has assumed that different voting rules would have prevented a Lai victory, without explicitly capturing preferences necessary to assess alternate electoral systems. Nor has such discussion about alternate voting systems addressed how such changes may create additional challenges to legitimacy.

Taiwan has enacted various electoral reforms in the past twenty years, from dissolving the National Assembly designed to represent the whole of China, to discarding the single non-transferable vote (SNTV) system for the Legislative Yuan in favor of a mixed member system while halving the number of legislative seats, to consolidating local elections and placing presidential and legislative elections on the same day. Yet, no substantive reform has been proposed for how presidents are elected, despite potential concerns of a winner potentially lacking a mandate.

This paper links the thought experiment of elections under different rules with original pre-election survey data assessing candidate preferences. This preference ordering is then used to simulate what the outcome would have been under two forms of preferential voting, the alternative vote and Borda count, and whether the simulated outcomes differ from the actual result of a Lai victory. I first provide a brief literature review on the effects of electoral systems on competition, with emphasis on variations in preference voting, connecting this to the Taiwan context. The results of the original survey showed a Ko Wen-je victory under both preferential systems, with a Hou victory if weighting the older respondents in line with their national population. Next, using the rank ordering of the survey to derive estimates from the actual presidential election, the results show, counter to conventional wisdom, that Lai would have likely narrowly won under the alternative vote, but would have lost to Hou under the Borda Count by a margin even smaller than Taiwan’s closest presidential election in 2004. The results suggest the limitations and potential tradeoffs associated with moving away from the current system. The conclusion expands on the ramifications of electoral system differences and avenues for future research.

Literature Review

A broad literature addresses the effects of electoral systems on the number of parties and styles of competition (e.g. Duverger 1954; Moser 1999; Sartori 1999). The assumption remains that voters as well as parties adapt to the incentives of the electoral rules (e.g. Norris 2004; Krauss and Pekkanen 2004), although how quickly is less clear. For example, regarding Taiwan’s implementation of a mixed member legislative system to replace the single nontransferable vote (SNTV) system starting in 2008, survey work suggests a public with limited knowledge of the new system (Rich 2014).

Whereas moving to a mixed member legislative system may require time to understand the complexities of strategic incentives under the two votes, one may assume a quicker grasp of any potential change to how the president would be elected. Voters may have informally considered institutional alternatives in races that included more than two candidates already. For example, Taiwan’s three-candidate presidential election in 2000 led to Chen Shui-bian of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) winning with only 39.30 percent of the vote. This outcome would not have occurred without a split between KMT candidate Lien Chan (23.10%) and former KMT member James Soong (36.84%) (see Niou and Paulino 2003), the latter of whom would have won under a runoff system commonly employed in presidential elections in Latin America. Likewise, if voters were considering a strategic vote if convinced their preferred candidate would not place in the top two, they would have informally engaged in a ranking as well.

Moreover, as the three presidential candidates in 2024 had clearly distinguishable ideological positions, voters who based their ranking on ideology should not have had to struggle to rank candidates rationally. Whether the traditional left-right ideological spectrum fits the Taiwan case may be disputed (e.g., Jou 2010; Chen and Beattie 2023), but positions on Taiwan’s status vis-à-vis China traditionally play a similar role, separating the DPP from the KMT. As a younger party, having only formed in 2019, the TPP’s positions have been more fluid and less cemented in voters’ minds, but presidential candidate Ko attempted to position the party as a break from the traditional green (independence) or blue (unification) divide, which could be read as being in between the other two camps ideologically.

Simple runoff systems attempt to mitigate some of the structural concerns associated with first past the post single member districts, such as winning with only a fraction of the vote or the roles of spoiler candidates and strategic voting (Niou 2001; Bouton 2013; Van der Straeten, Laslier, and Blais 2016). Seeing the inability of Hou and Ko to agree upon a joint ticket in November, such concerns become less relevant with a runoff. Instead, a runoff would have likely pitted Lai against one of the opposition candidates, giving a clear choice to those opposed to Lai and who retrospectively evaluated the Tsai administration negatively, thus minimizing the likelihood of a Lai victory. The campaign rhetoric in the first round would likely have looked similar to what was seen in January as the system would encourage both opposition candidates to target each other as well as Lai, only pivoting after the first round to attempt to win over the second round votes from the dropped candidate. Yet critics are quick to point out that runoffs are not a cure-all. They do little to reduce negative campaigning, and perhaps in fact encourage it to increase in the second round, while the system is more costly and typically sees lower turnout in the later runoff, potentially distorting public sentiment (Richie 2004). In the Taiwan case, with the history of personality disputes between the TPP and KMT, the dropped opposition candidate may have had little incentive to encourage supporters to vote for Lai’s remaining opponent.

However, a runoff system is not the only system which a reform-minded Taiwan could consider. Under the alternative vote system, if no candidate wins an outright majority in the first round, the worst-performing candidate is dropped and their voters’ second-preference votes are allocated to remaining candidates, which step is repeated if necessary until a candidate receives a majority of the vote. Unlike traditional runoff systems however, voters only need to vote on one occasion, with the reallocation done based on the initial ranking of options. The system, used most notably for Australia’s House of Representatives, typically encourages multiparty competition and also encourages like-minded parties to coordinate ranking efforts, often favoring candidates that stake out moderate positions. In the Taiwan case, even with personality disputes, the alternative vote would likely encourage candidates to make direct appeals for second preference votes, with the assumption that most voters for one of the opposition candidates would name the other opposition candidate second. John, Smith, and Zack (2018) suggests the system performs better at descriptive representation than first past the post. In addition, voters do not seem to struggle to understand the system. Proponents also suggest the system avoids weaknesses inherent in proportional representation (Hain 1997).

However, the system assumes a full ranking of candidates, forcing voters to rank candidates they may know little or feel indifferent about, with this potentially leading to incomplete ballots, or so-called “donkey voting,” where voters simply rank candidates based on their order on the ballot (Jansen 2004). In the Taiwan case, with only three candidates, ignorance about the candidates is likely minimal, so the system would likely have functioned much like a runoff system, but in one night. However, the same issue as with a runoff could emerge if the likely dropped candidate, Hou or Ko, did not encourage a full ranking, thus depriving the remaining candidates of second votes.

A less commonly suggested preference voting system is the Borda count, used in Kiribati and Slovenia[1] and perhaps more well known for its use in Major League Baseball’s Most Valuable Player Award and college football’s Heisman Trophy. Here candidates receive points based on their preference rankings with the highest point total winning. For example, in a four-candidate race, a voter whose preferences were Candidate A > Candidate B > Candidate C > Candidate D would ultimately allot 4 points for Candidate A, 3 for B, 2 for C, and 1 for D.

The Borda count shares many of the same purported strengths as the alternative vote, while ensuring the transitivity of preferences (Saari 1994) and often coincides with the Condorcet winner (Merrill 1984; Tangian 2013). Here again, the presence of both Hou and Ko would not produce a spoiler effect guaranteeing a Lai victory. However, voters may still manipulate the system by failing to rank all the candidates, and if voters choose to only list a first preference, Borda will function akin to a first past the post plurality vote (Emerson 2013). This system may also incentivize the proliferation of like-minded candidates as a means to increase overall point totals. Thus, rather than attempting to coordinate on running one presidential candidate, under these rules, the KMT and TPP would potentially benefit from nominating additional but lesser known partisans to inflate artificially their point total.[2] Where voters have a clear majority preference for one candidate in a three-candidate race, these preference options should not result in outcomes different than first past the post. However, in competitive races, especially where ideological similarities between two candidates and distinct animosities for a third exist, the use of preferential systems would potentially produce a different outcome, as would have been expected if either of the options above had been in place in 2000.

A crucial point here, however, is that while preference options may generate a different winner, how that win ultimately is formulated can differ in significant ways, with potential implications for leadership and for accepting the legitimacy of the victory. In short, a preferential system that manufactures a clear majority aims at mollifying partisan tensions, while one that simply addresses preferences but lacks a manufactured majority risks entrenching polarization and animosity.

Research Design and Empirical Analysis

I surveyed 1,213 Taiwanese via web survey on December 1–11, 2023, administered by the survey company Macromill Embrain, employing quota sampling for gender, age, and geographic region. This produced a sample which was 53.09% female, a percentage slightly above that of the population (approximately 51%), and an average age of 41, similar to the median age of the population, with a range from 18 to 78. A common concern about web-based surveys is the underrepresentation of older respondents. In this sample, those 65 and older in particular were underrepresented, comprising 3.38% of respondents in a population in which they comprise roughly 17% of the population. The sample also included respondents from each county and special municipality except for Penghu, Kinmen, and Lienchang counties.

First, I included a typical pre-election survey question regarding planned vote choice for the 2024 presidential election. Here a thin plurality chose Lai (28.77%) over Ko (26.05%) and Hou (21.68%). Surprisingly 23.5% of respondents stated that they did not plan to vote, although this likely captured those who had yet to decide who to vote for, with most polls in late November through December finding 10–25% of respondents had not decided on their vote choice. The results contrast with several of the late November-early December pre-election polls that saw Hou overtake Ko after the failure of the two to coordinate a unified campaign, and admittedly may be a function of both the timing and the web format.[3]

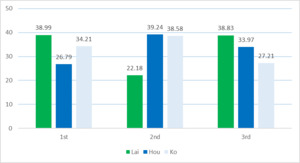

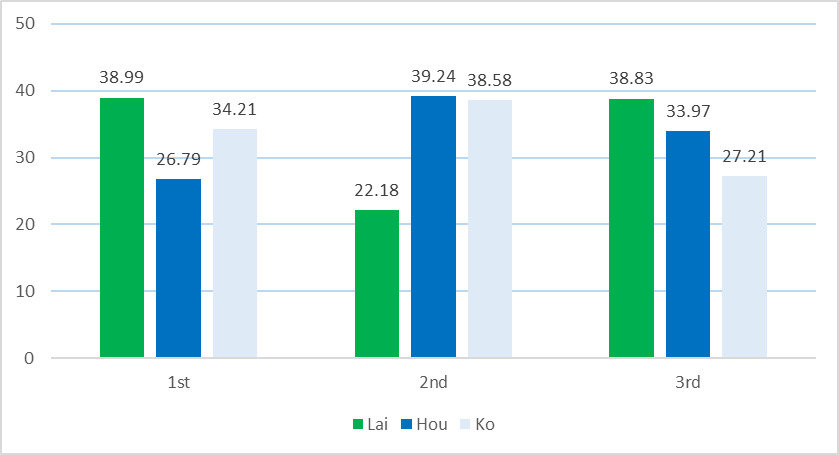

This however told us little about overall preference ordering or how those claiming not to have made up their mind may potentially vote. To tackle this, I next asked respondents to rank order the candidates with their most preferred candidate first and least preferred third. See Figure 1. Here we still see Lai with a small lead over Ko in first choice preferences (38.99% vs. 34.21%), albeit a larger lead than in the original question, while Hou appears further behind (26.79%). In terms of second preferences, both opposition candidates garnered remarkably similar vote shares (Hou: 39.24%, Ko: 38.58%). Those ranking Lai first predictably saw little preference for either opposition candidate, with Hou garnering 50.11% of second preference votes, whereas most respondents preferring first an opposition candidate chose the other opposition candidate as their second choice. Ko supporters however were far less likely than those of Hou to stick within the opposition camp (57.59% vs. 71.38%), perhaps in part due to lingering animosity following the breakdown of coordination talks.

Broken down by age cohort (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60+), we see clear differences in first preferences, with support for Hou increasing from 14.86% among the youngest to 48.18% among the oldest, and with Ko support moving in the opposite direction, from 61.14% to 15.15%. Among the youngest cohort, we also see Ko supporters only somewhat more likely to choose Hou as a second choice (54.21%) over Lai, compared to 66.67% of those in the oldest cohort. Likewise, a strong majority of the youngest Lai supporters ranked Ko second (73.81%), but among the eldest Lai supporters, 63.89 listed Hou second. In contrast, 76.92% of the youngest Hou supporters chose Ko second, with a similar rate among the eldest Hou supporters (75.00%).

Preferences can be unpacked in a few other manners. Prior to the preference ranking, the survey asked respondents about their planned vote choice. Overwhelmingly, people later ranked their first preference as they had indicated they would select in January, with little sign of strategic voting: Lai: 99.71%; Hou: 93.16%; Ko: 97.78%). Likewise, stated party preference largely corresponded with candidate choice: 76.56% of DPP supporters for Lai, 87.8% of KMT supporters for Hou, and 89.17% of TPP supporters for Ko.[4] Among those without a party preference, a plurality of those saying they intended to vote (24.23%) favored Ko, compared to Lai (18.77%) and Hou (16.55%), while a plurality overall (40.44%) stated at the time they did not intend to vote.

In addition, it should not be surprising that vote choice in 2020 would correspond with preferences in 2024. See Table 1. Among those voting for the DPP incumbent Tsai Ing-wen in 2020, nearly two-thirds ranked Lai first (65.84%), while supporters of the KMT candidate in 2020, Han Kuo-yu, similarly preferred Hou (70.59%). In contrast, a thinner majority of supporters of perennial presidential candidate James Soong of the People First Party (PFP) ranked Ko first, showing potentially significant benefit to Ko from frustration with the big two parties as opposed to ideological similarities between the PFP and TPP. Perhaps most interesting, a clear plurality of those who did not vote in 2020, either because they chose not to or were ineligible (e.g., were under the voting age), preferred Ko, with Hou and Lai garnering first preferences similar to each other among this group.

Based on the elicited preferences, Table 2 takes the rank order raw responses and presents calculations of simulated elections under two systems: the alternative vote and the Borda count.[5] The data suggests that the alternative vote would lead to a Ko victory. With Hou’s third place finish, reallocation of votes would provide Ko a modest majority (53.34%). Whether this would be the same result as under a runoff election held weeks later could only be conjecture as it would be difficult to estimate the degree to which turnout would differ in the second round of an actual runoff. However, under the Borda count system, Ko would still be victorious according to the pre-election survey, albeit with a much narrower margin of victory, garnering 34.50% of the vote points over 33.36% for Lai. Under current law, a recount must occur if the difference in votes between the top candidates is less than 0.7%, which would be avoided in this scenario with Ko’s 1.14% lead over Lai. Here the second preference points clearly benefit the opposition candidates, presenting Hou as more competitive than the first past the post results would suggest, while providing Ko a meager boost over Lai.

Acknowledging the age biases in the survey, I also reran the simulations, testing different weights for 65+ respondents. Only by weighting this group four times higher (thus representing 15% of the sample), does Hou make it to the second round under the alternative vote system, soundly defeating Lai (57.63% vs. 42.36%). However, at this level, Ko would still win under the Borda Count with 33.54% to Lai’s 33.21% and Hou’s 33.25%, albeit by a margin of 0.29%, leading to an immediate recount under current law.

From here, I used the rank ordering from the original survey to estimate how preference voting might have altered the results of the January election. I assumed that the rank ordering of candidates remained the same as in the pre-election survey. Thus, among those preferring Lai, the assumption was that 50.11% would rank Hou second versus 49.89% for Ko, with the percentages reversed for third preference. For those preferring Hou, 71.38% would rank Ko second compared to 28.62% for Lai, while a majority of those preferring Ko would give their second preference to Hou (57.59%) over Lai (42.41%). This helped address that support for Hou across polls increased over December and that Hou was likely to outperform Ko at the end. Using the actual election results as first preferences and then reweighting the 1,213 survey responses to reflect both these and the subsequent second and third preferences provided an estimation of how the 2024 election would have looked under different formulas. Table 3 presents the results. Using the alternative vote here results in the votes for third-place Ko being reallocated to the other candidates, ultimately resulting in a narrow victory for Lai (51.28%). However, using the Borda count produces an even narrower victory than in the original survey, although this time for Hou (33.75%). Thus, even with only 57.59% of Ko voters listing Hou second, these second preference votes would have been enough for Hou to eke out a victory.

Overall, the results show the extent to which Lai Ching-te benefited from split opposition. In the original survey, where support for Ko was still relatively high, both preference voting options converged on Ko as the winner, with the alternative vote generating a 6.68% margin of victory in the second round, and Ko winning under Borda by 1.14%. Shifting to the models incorporating the actual results weighted by the survey shows that, despite beliefs that the fractured opposition was the main factor allowing for a Lai victory, under the alternative vote system, he would still eke out a victory, albeit with a smaller margin (2.56%). However, under the Borda count, Hou would win by 0.14% of the vote, less than the difference in Taiwan’s closest presidential election (2004). The results suggest not only the extent to which moving from first past the post may produce different outcomes, but perhaps suggest a cautionary tale for the Borda count. If the goal of electoral reform is not only to avoid wasted votes and a spoiler effect but also to create definitive winners, the evidence here suggests the Borda count may exacerbate partisan tensions by producing winners both lacking majority support and also winning via very narrow margins.

Conclusion

Electoral systems by definition translate votes into seats, benefiting certain types of candidates over others. The results here give insight into the extent to which the 2024 presidential result could have been different under two systems that attempt to minimize a perceived weakness of the first past the post system, namely that of a wasted vote. Under the pre-election survey, the results suggest a Ko victory, and if weighted to take into account biases in the age distribution of the sample, suggest a Hou victory. The simulated preferential voting based on the actual election results suggests Lai would still win under the alternative vote. However, he would lose a very close race to Hou under the Borda count, where Hou would capture 33.75% of the total vote to Lai’s 33.61% and Ko’s 32.64%. This difference of about 0.14% would, by being under 0.7%, automatically trigger a recount under current law. While the assumption is that the Borda count is most likely to generate a Condorcet winner (e.g. Van Newenhizen 1992), this does not take into consideration the normative and perceptual challenges that could ensue if such an election produced such a narrow margin across all candidates. Under such conditions, even with the recount rule, one may expect protest of the outcome, similar to that of the 2004 presidential election, and weakened confidence in the winner having a mandate to lead.

Admittedly, the original survey analysis was an imperfect means to evaluate how preferential voting systems would work under either the alternative vote or Borda count, as it could not capture aspects such as strategic voting, and it assumed, too, that the survey responses ranking candidates captured sincere preferences. Likewise, estimation of preference voting from the results of a first past the post election assumed both that the preferences in the December poll remained stable, questionable as Hou increasingly appeared to become the stronger opposition candidate, and also that voters would not behave differently under new rules. While preference ranking appears straightforward, voters with no experience under such a system may misunderstand how to cast a vote or deliberately only vote for their preferred candidate. If a preferential system had been in place, this also may have influenced ultimately the number of candidates no longer worried about generating a spoiler effect, with additional candidates opting to run and less incentive for candidates like Terry Gou to drop out.

Several avenues for future research emerge from these findings. Although the focus here was on presidential races, the same potential dynamics could be analyzed at the legislative district level, where third party candidates are commonplace. In addition, while preference ordering in the pre-election survey followed general expectations, the strength of these preferences may be captured better through a combination of qualitative and quantitative measures. Similarly, measuring rank ordering over time could better capture stability of these choices, while measures of satisfaction with the results post-election may give a clearer sense of how reforms may shift views of the system more broadly.

A modified version is also used in Nauru.

For example, a KMT supporter in a three-way race might allot 3 points for Hou, 2 for Ko, and 1 for Lai. By adding an additional KMT candidate, Hou supporters would now pick up 4 points for first preferences while likely picking up additional second preferences as well.

Virtually all public opinion polls from late November through December showed Lai with a 3–5% lead, usually around 32–37%, with the United Daily News December 13–17 poll an outlier showing Lai and Hou tied at 31% and 21% for Ko. Within this time frame, Ko typically polled in third place, with the December 23–25 CMM Media poll an outlier, having Ko polling at 27.8% to Lai’s 29.5%.

The survey unfortunately did not ask respondents about voting intentions in the concurrent legislative elections, which could have identified intentions to split their ticket.

Since there are only three candidates, the results from simulating a runoff system would appear identical to those of the alternative vote.